Suggested Donation Levels

What have you learned?

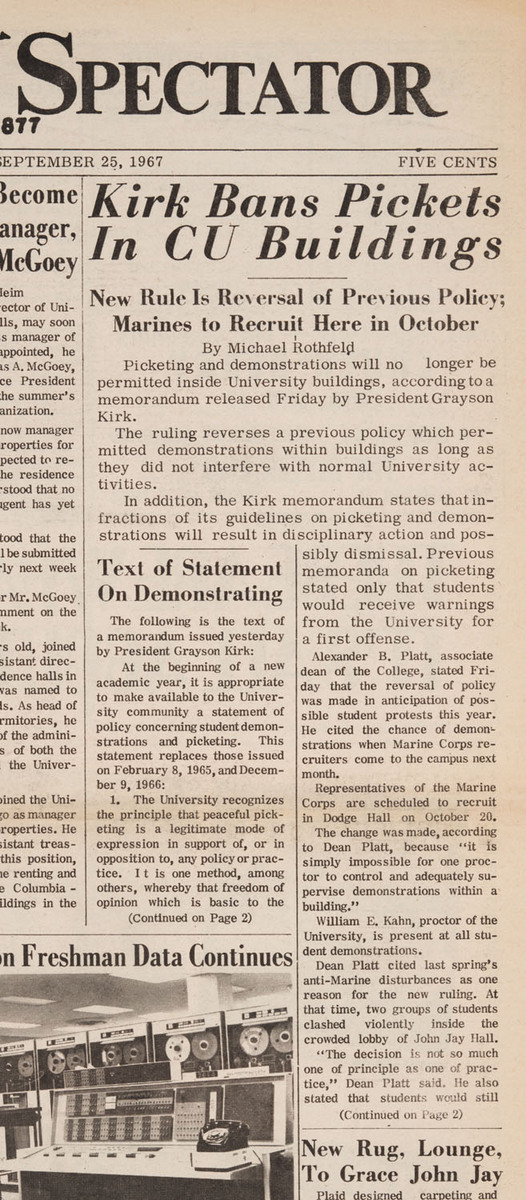

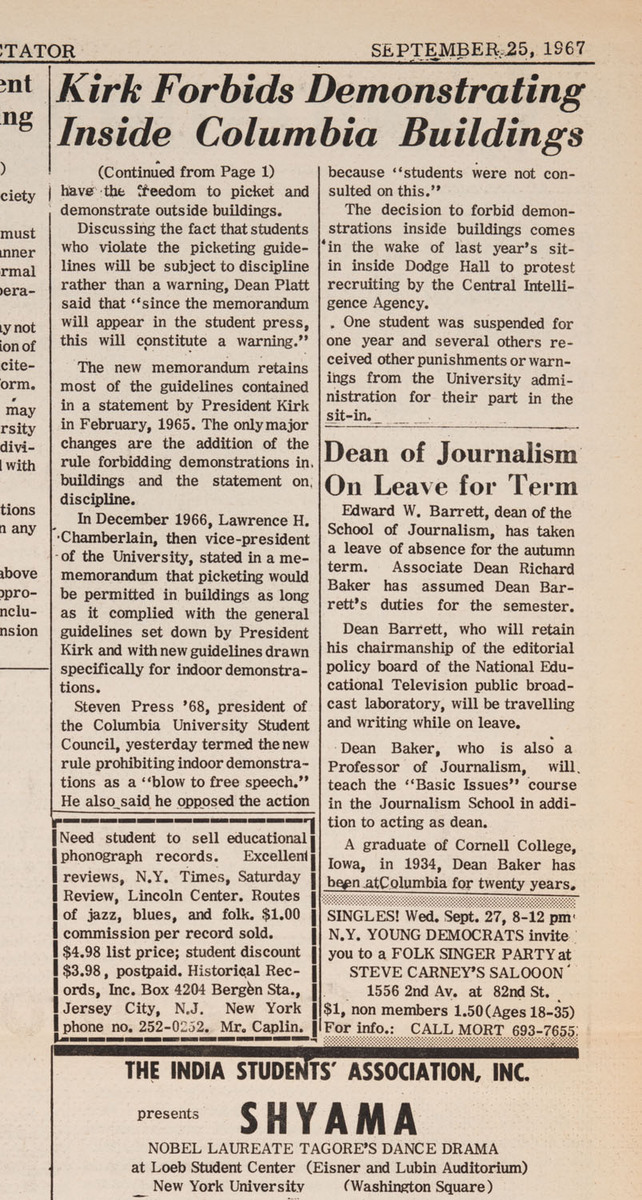

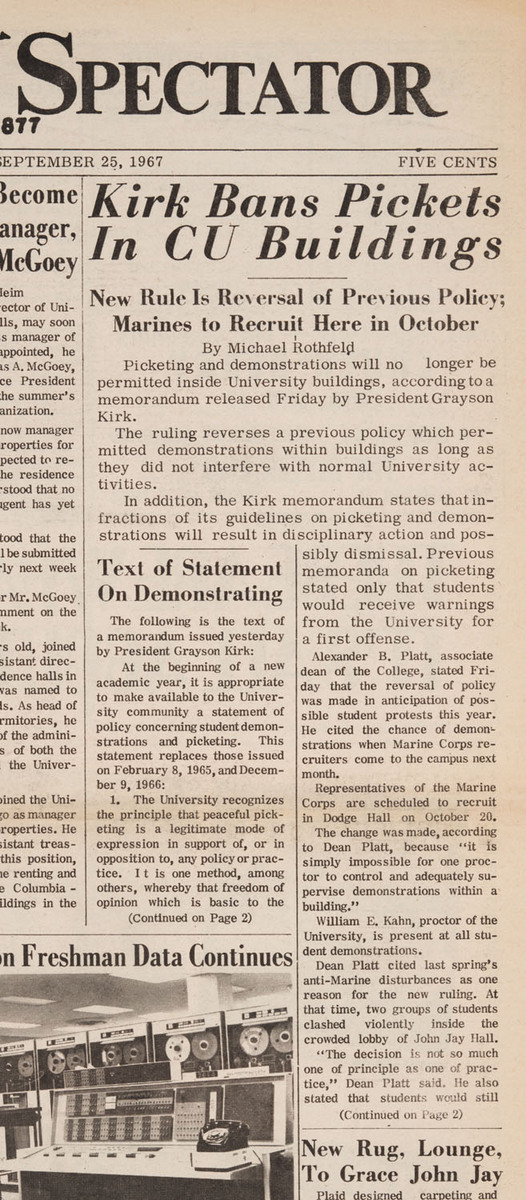

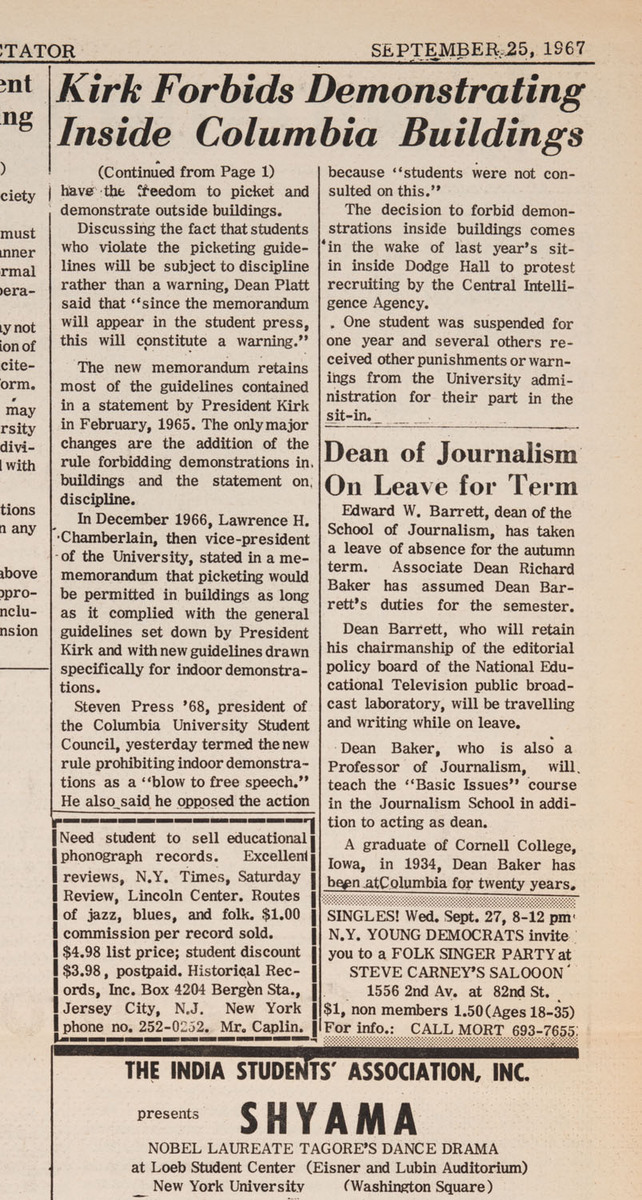

"Kirk Bans Pickets in CU Buildings: September 25, 1967 "

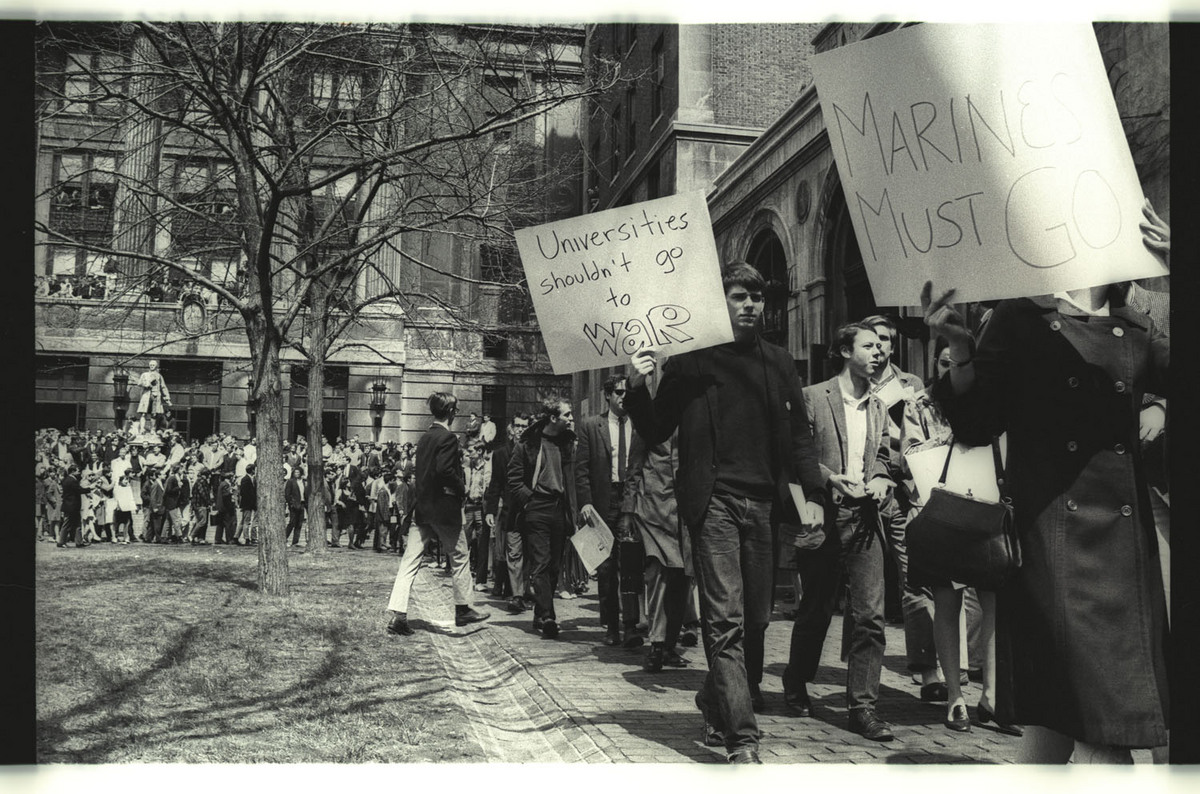

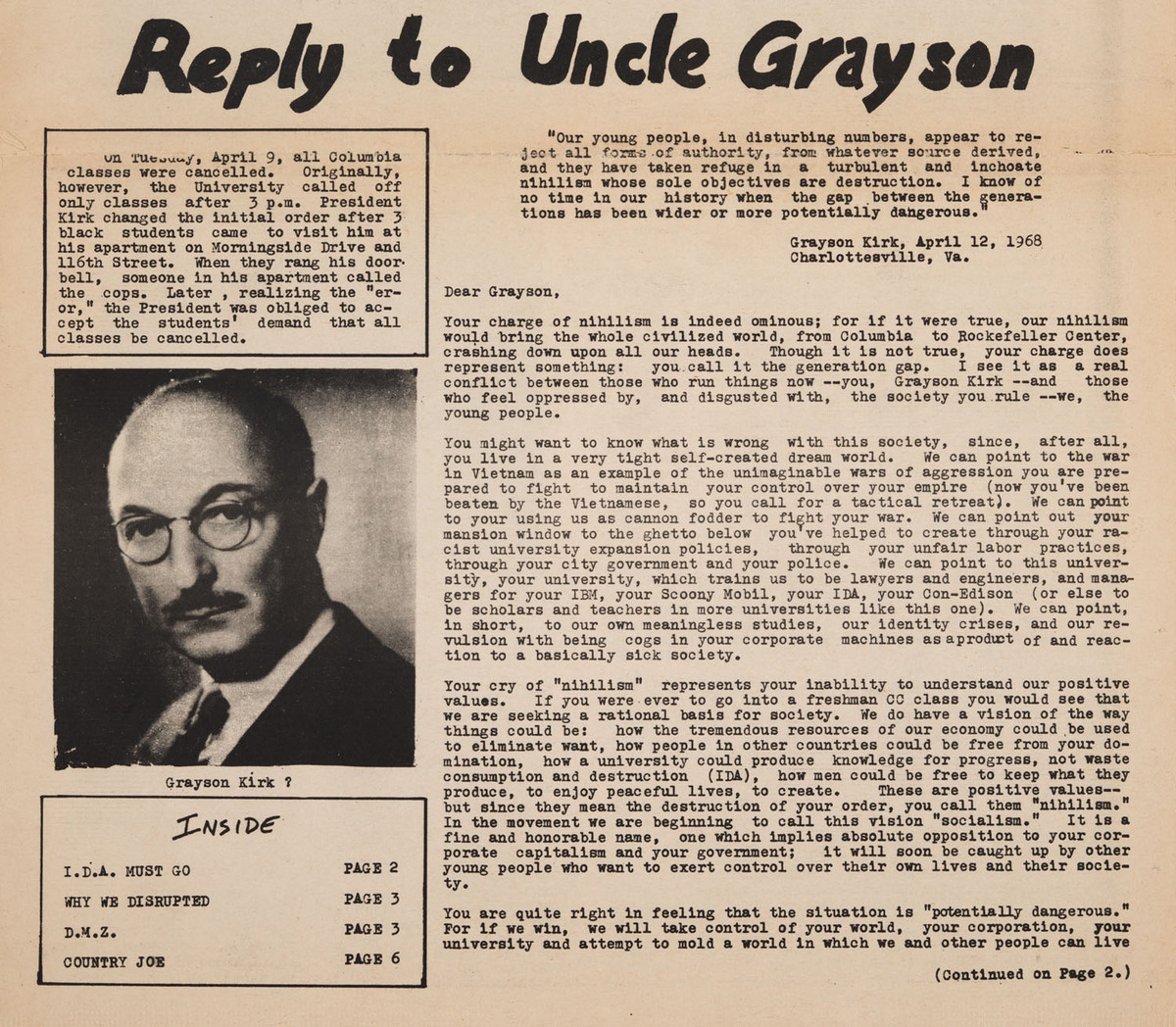

On April 21, 1967 the first student-to-student clash erupted when 500 students favoring the policy of open recruitment on campus confronted 800 anti-recruitment demonstrators. Student disruption of military recruiters prompted University President Grayson Kirk to issue a ban against picketing and demonstrations inside all University buildings as of September 1967.

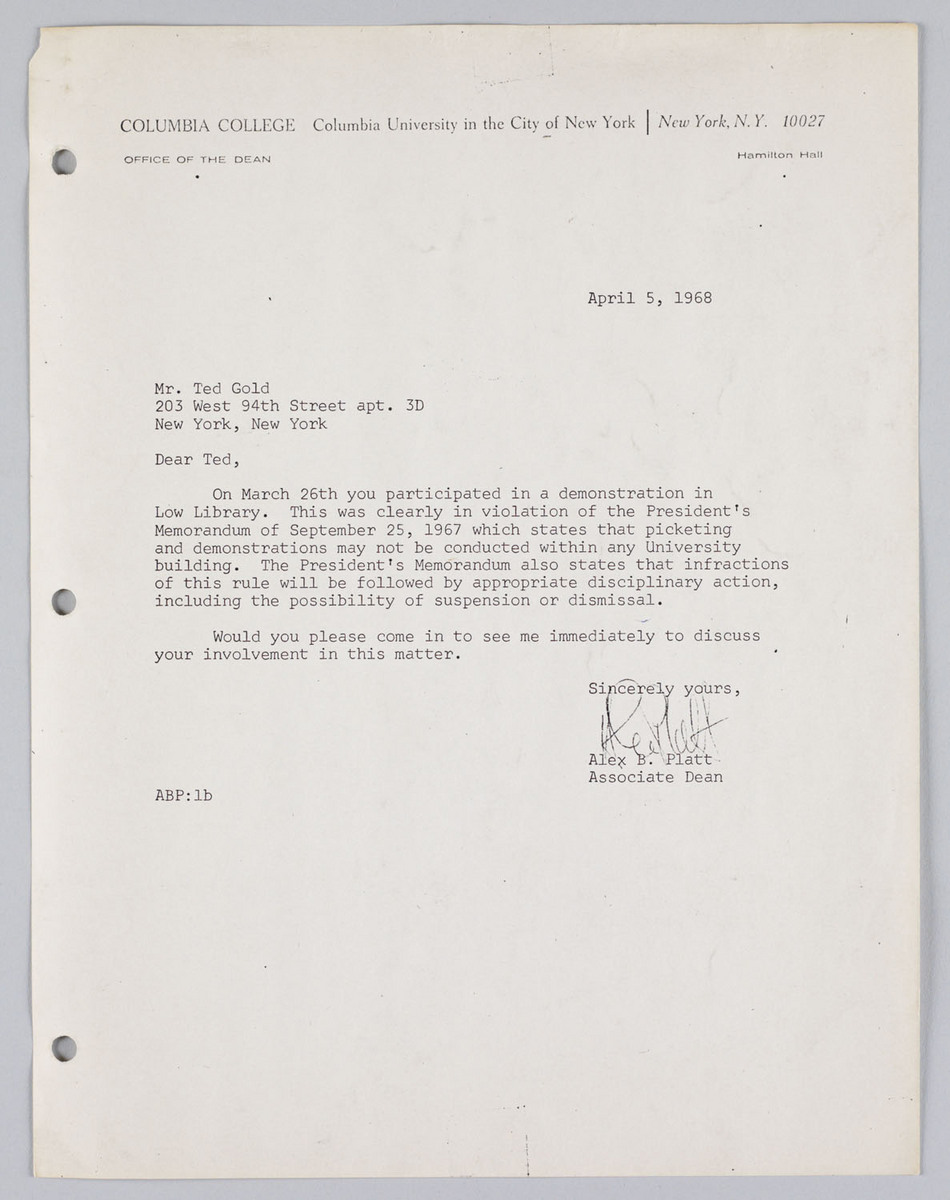

Associate Dean, Alex B. Platt to Columbia College student Ted Gold, April 5, 1968

In March 1968, SDS defied this policy, staging a demonstration inside Low Library demanding Columbia’s resignation from IDA. Despite limited enforcement of his ban on indoor demonstrations prior to this event, President Kirk placed six of the 150 anti-war student activists – all SDS leaders later known as the “IDA Six” – on disciplinary probation. One of the principal demands that SDS promoted at the April 23rd Sun Dial rally was amnesty for the “IDA Six.”

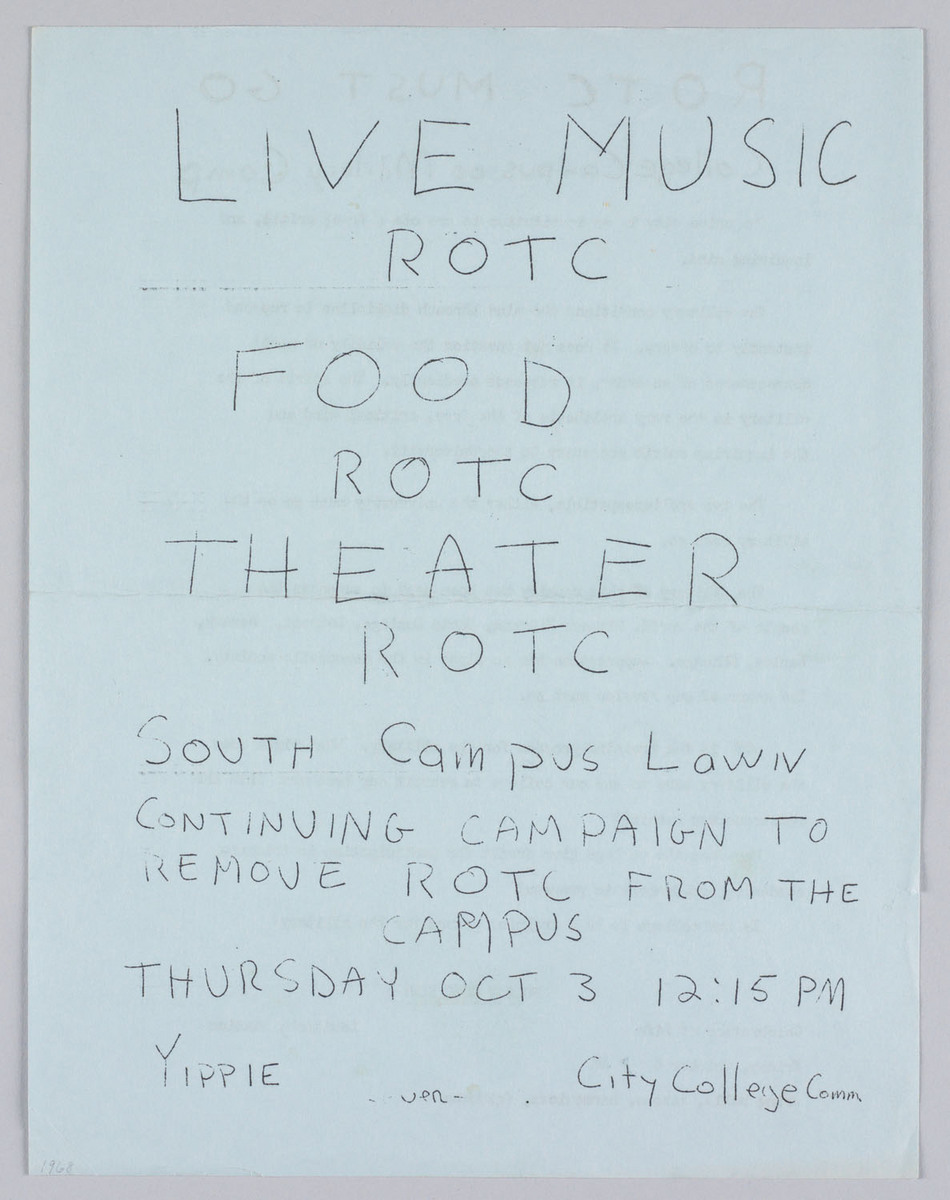

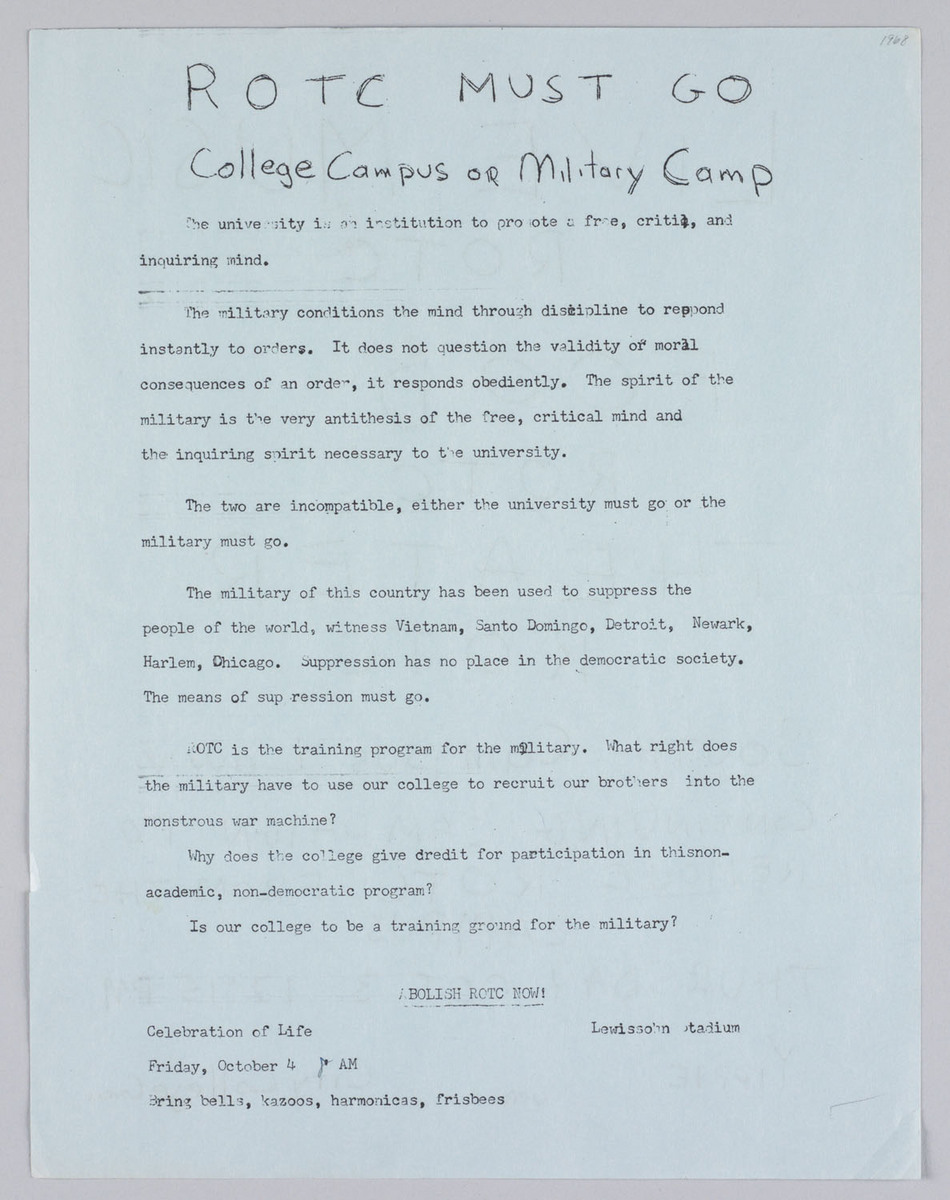

"Live Music, ROTC, Food, ROTC, Theater, ROTC"

Blue circular, hand written advertising campaign to remove ROTC from college campuses

Tuesday April 23

TUESDAY APRIL 23

Noon SDS Sundial Rally

12:40 p.m. March on gymnasium site, Morningside Park

2:00 p.m. Sit-in begins in Hamilton Hall; Dean Henry Coleman restrained from leaving his office by protesting students

2:50 p.m. Six Demands forumlated; students decide not to leave until demands are met

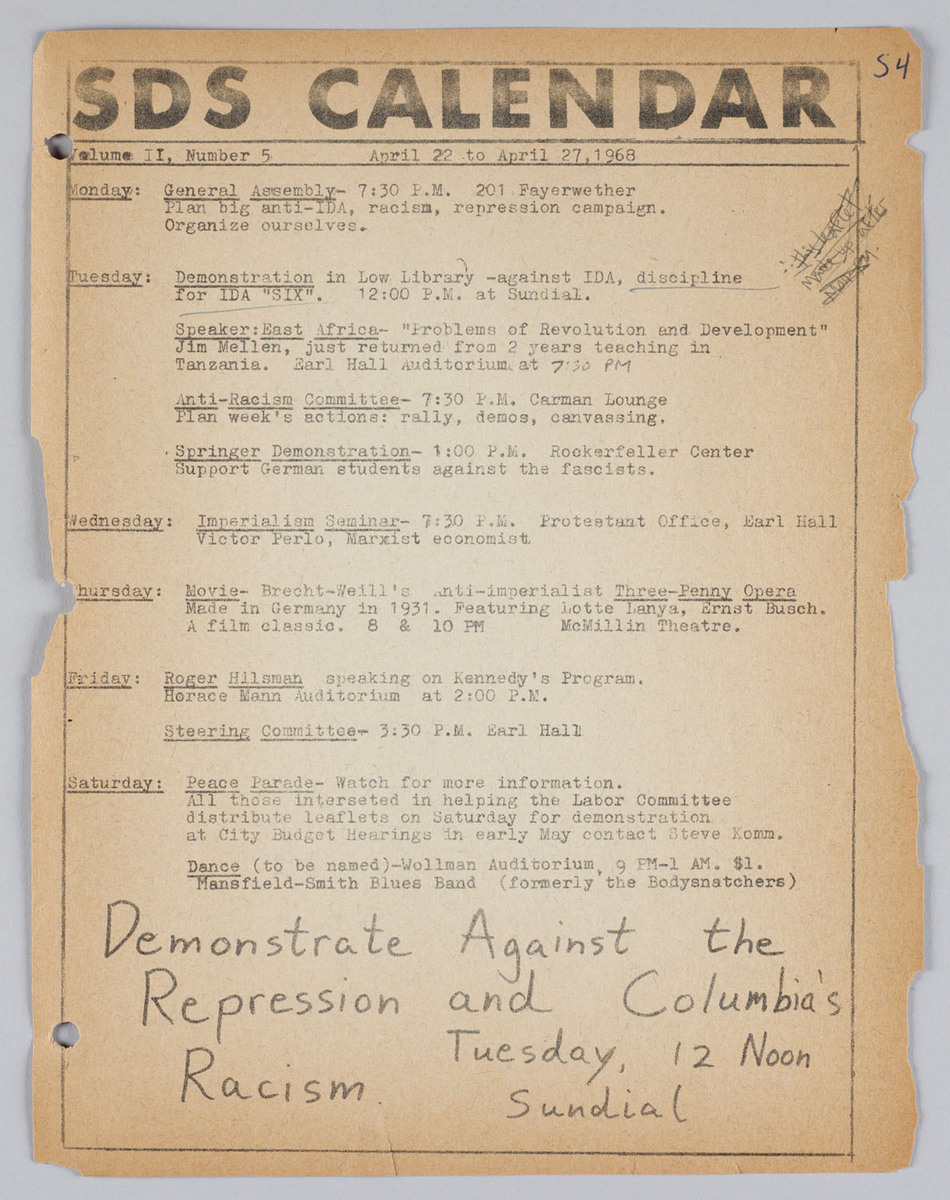

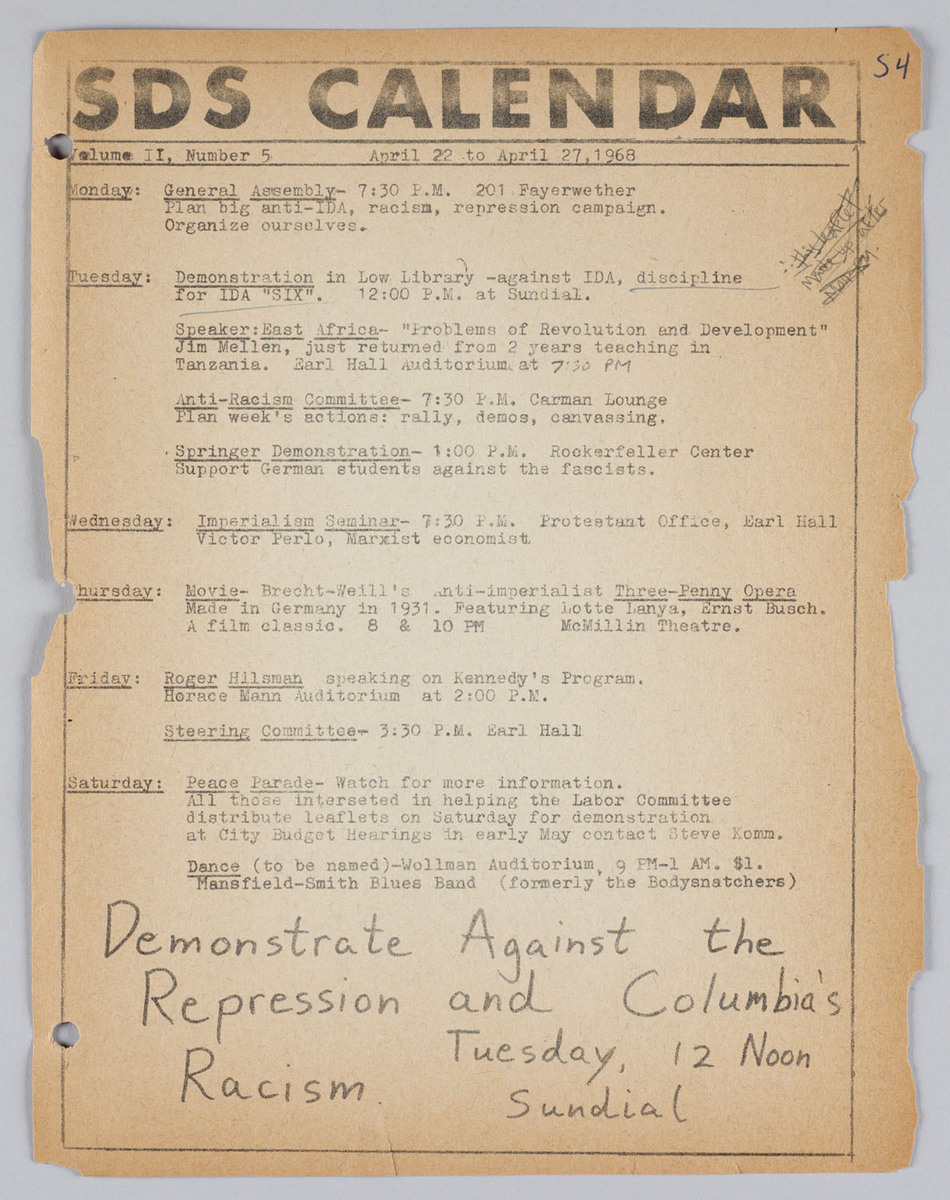

Original calendar of events proposed by SDS for the week of April 22 to April 27, 1968.

Wednesday, April 24

WEDNESDAY April 24

5:30 a.m. White students evicted from Hamilton Hall by black students

6:15 a.m. Students break into Low Library and seize President Kirk's offices

10:00 a.m. Faculty with offices in occupied Hamilton Hall begin congregating in 301 Philosophy Hall

3:30 p.m. Dean Coleman released from Hamilton Hall and goes directly to the Faculty meeting being held in Havemeyer Hall

8:00 p.m. Administration makes unsuccessful compromise offer to black students

Evening Avery Hall occupied by architecture graduate students who refused to vacate the premises.

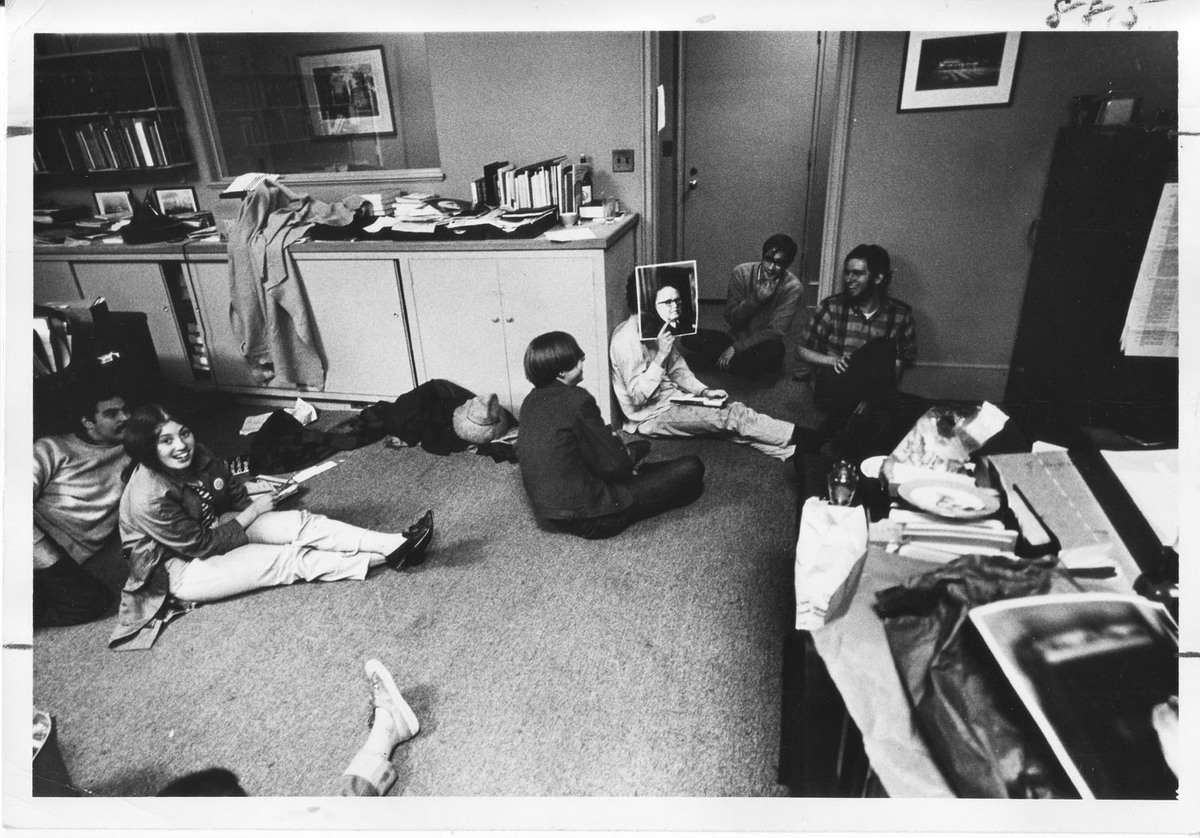

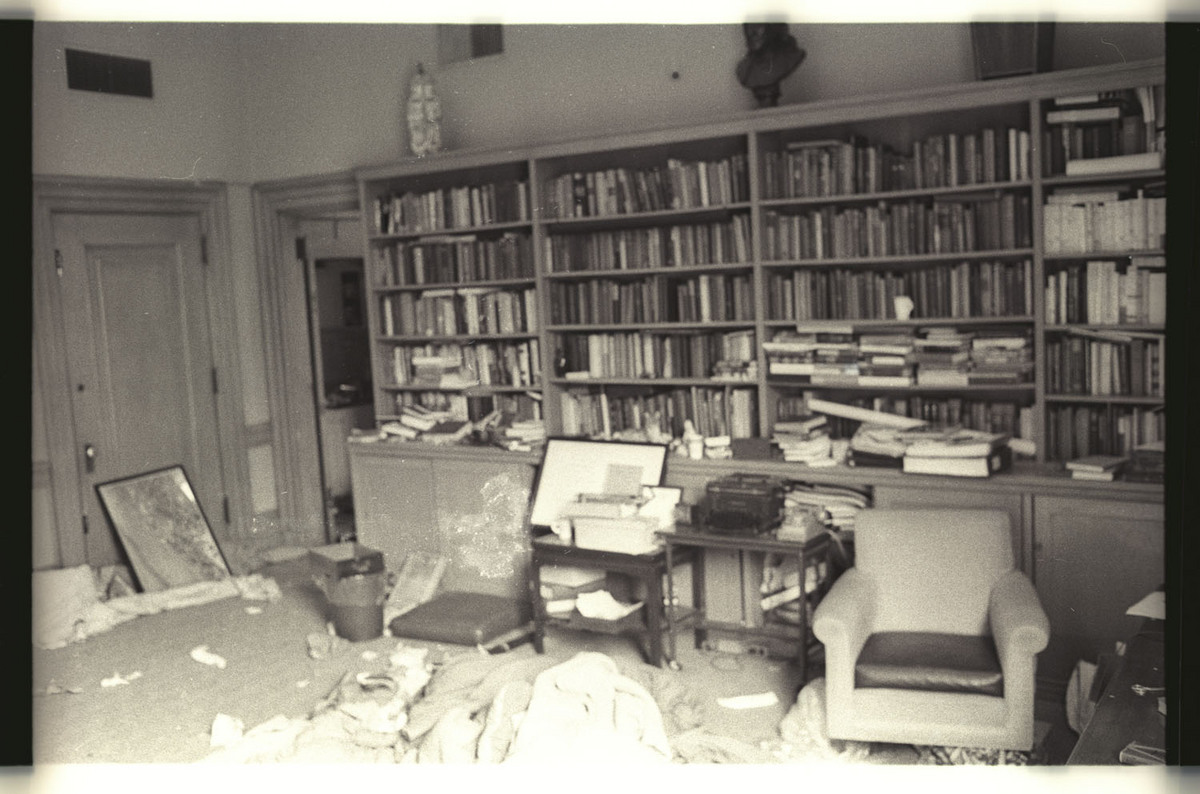

Students occupying President Kirk's office

Courtesy of Columbia College Today, Larry Mulvehill, photographer, 1968

THURSDAY, April 25

THURSDAY, April 25

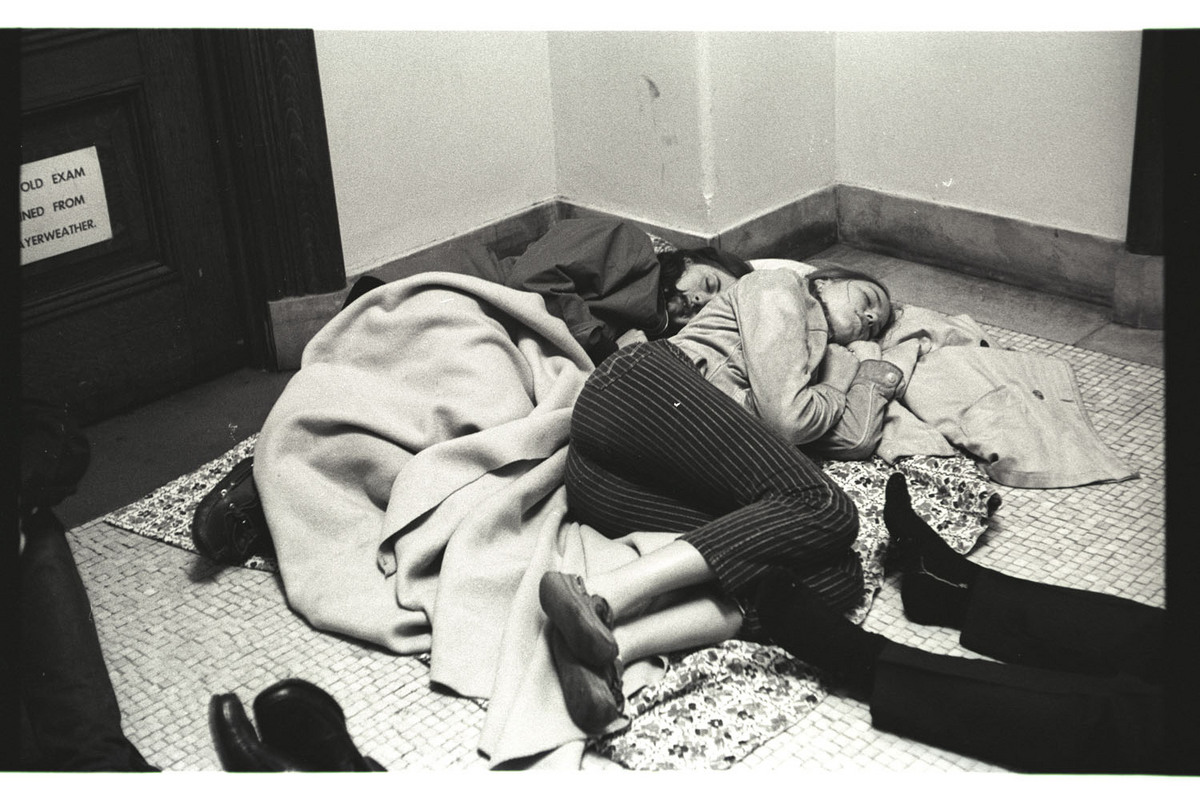

2:00 a.m. Fayerweather Hall occupied by students from the graduate faculties, mainly from the social sciences

4:00 p.m. Formation of the Ad Hoc Faculty Group; formulation of its first proposals to end demonstrations

7:00 p.m. - 8:00pm Strikers reject Ad Hoc Faculty proposals

8:00 p.m. Harlem activists address rally at Columbia gates, march across campus

Evening Counter-demonstrators are dissuaded by Ad Hoc Faculty Group members from attempting to invade Fayerweather Hall

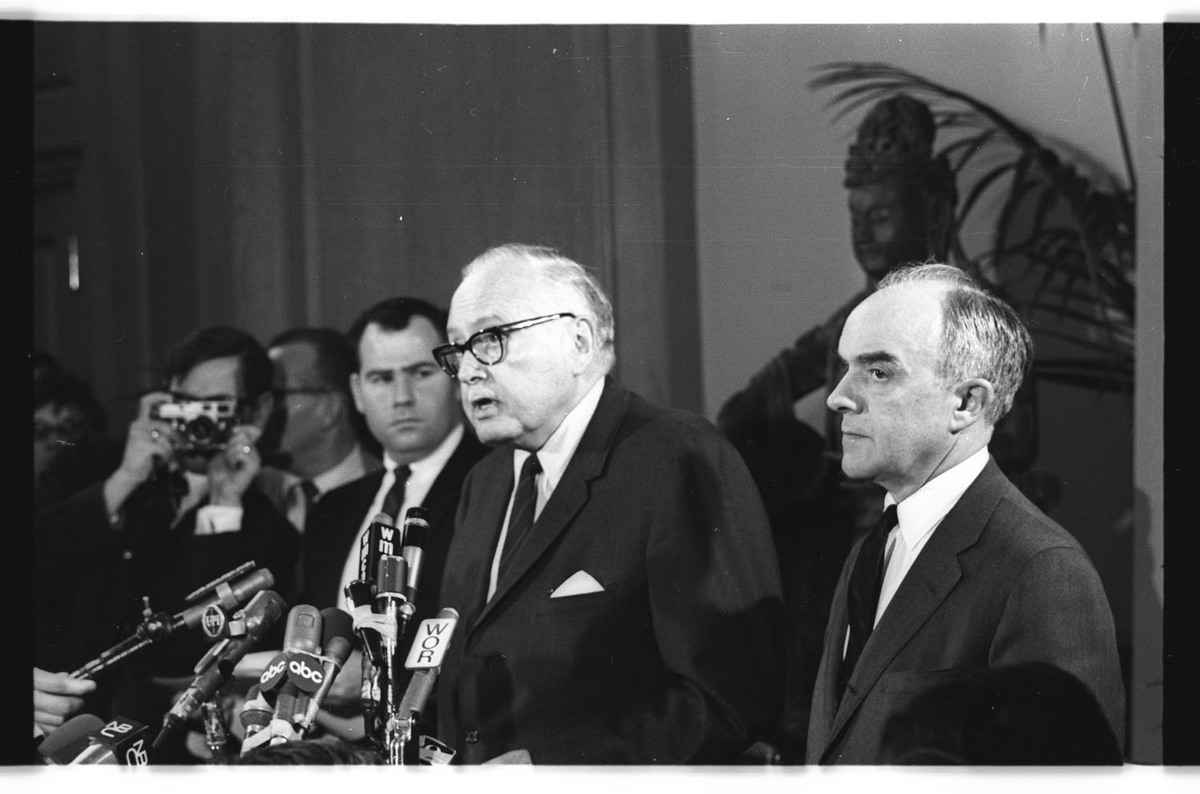

Grayson Kirk and David Truman at press conference in the Faculty Room of Low Memorial Library, April 25, 1968

FRIDAY, April 26

FRIDAY, April 26

1:05 a.m. Provost Truman announces impending police action to Ad Hoc Faculty Group

1:05 a.m. Mathematics Hall occupied by radical/hard line students from Low and Fayerweather

3:20 a.m. As a result of strong faculty opposition, Truman announces police action canceled; gym construction suspended

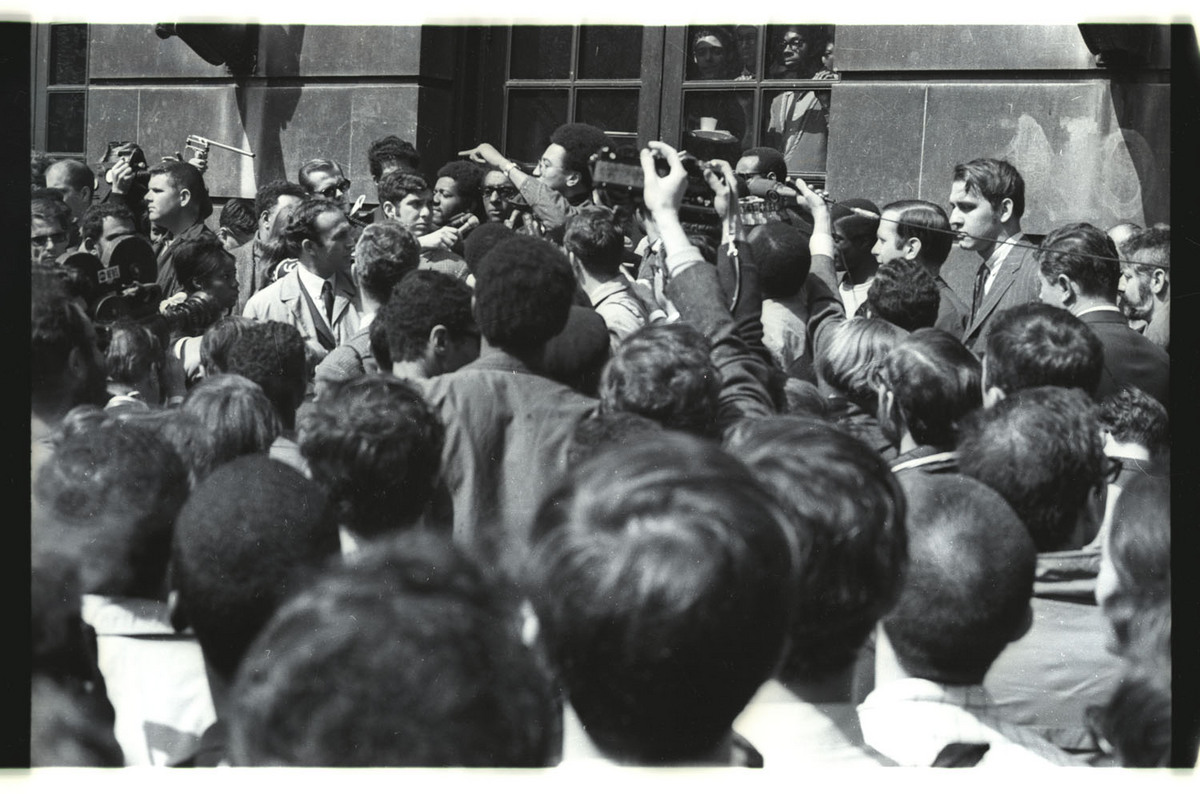

1:10 p.m. H. Rap Brown and Stokley Carmichael enter campus

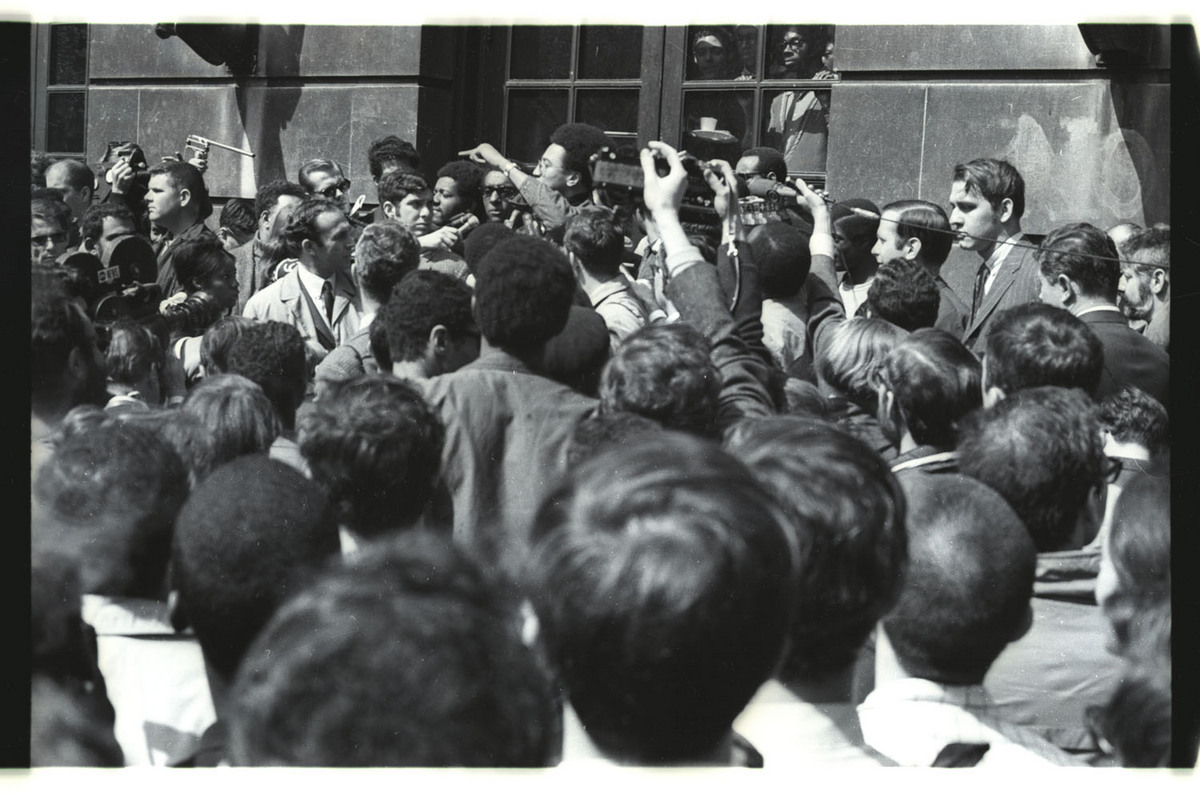

H. Rap Brown reading Hamilton Hall statement, Friday, April 26, 1968

Courtesy of Lee T. Pearcy '69C

SATURDAY, April 27

SATURDAY, April 27

1:00 a.m. Mark Rudd delivers "bullshit" speech before Ad Hoc Faculty Group, rejecting their efforts at mediation that does not include amnesty for striking students

Morning. William Petersen, chairman of the Trustees, releases a hard line statement regarding the situation on Columbia's campus

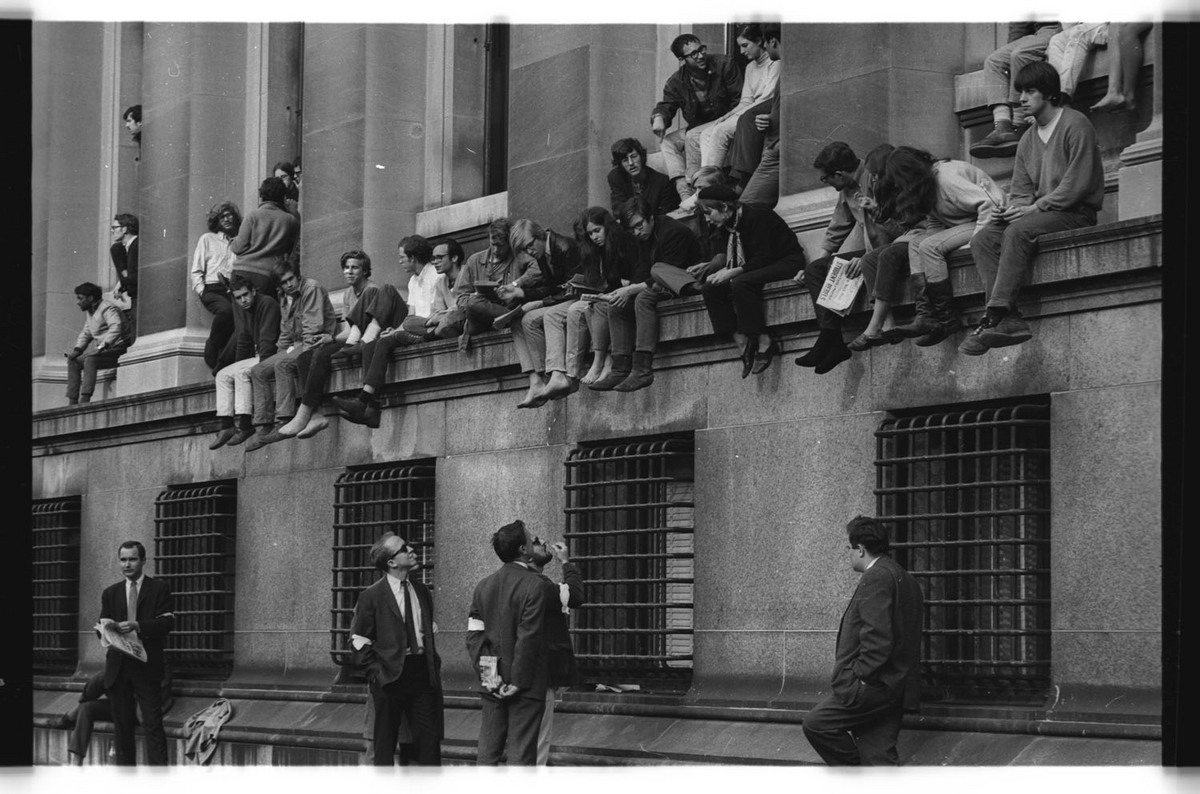

11:30 a.m. Faculty cordon around Low Library established to prevent access to demonstrators

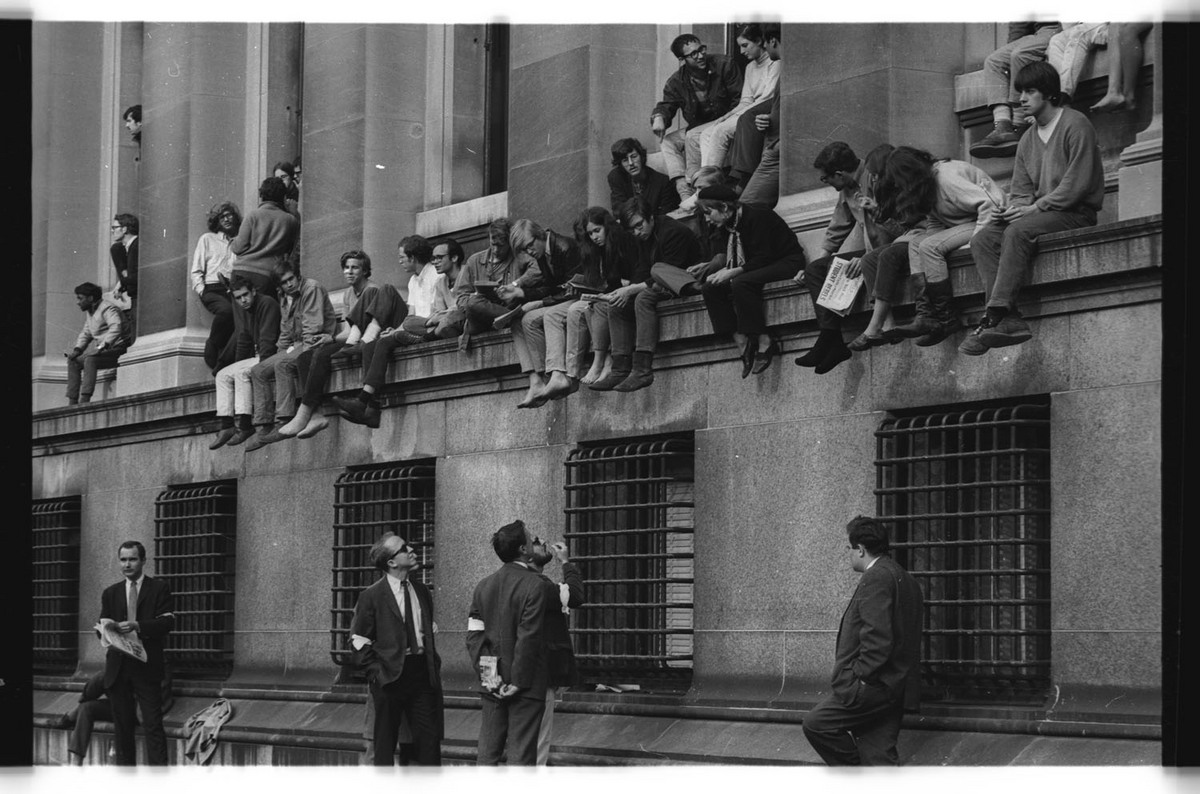

Faculty members talking to students occupying Low Library.

SUNDAY, April 28

SUNDAY, April 28

8:00 a.m. Ad Hoc Faculty Group announces final resolution ("bitter pill") to end crisis

5:00 p.m. Majority Coalition establishes cordon around Low Library

Evening Demonstrators attempt to pass food through counter-demonstrators' cordon into Low Library

In this image the faculty members wear white armbands, the Majority Coalition members wear light blue armbands and sole occupying student on the building ledge wears a red armband.

Courtesy of Columbia College Today

MONDAY, April 29

MONDAY, April 29

3:30 p.m. President Kirk issues negative response to "bitter pill" resolutions

6:30 p.m. Strikers reject "bitter pill" resolutions

11:30 p.m. Ad Hoc Faculty Group appeals to Mayor Lindsay, tables amnesty motion

Evening. Majority Coalition reluctantly accepts "bitter pill" resolutions; withdraws its cordon from around Low Library

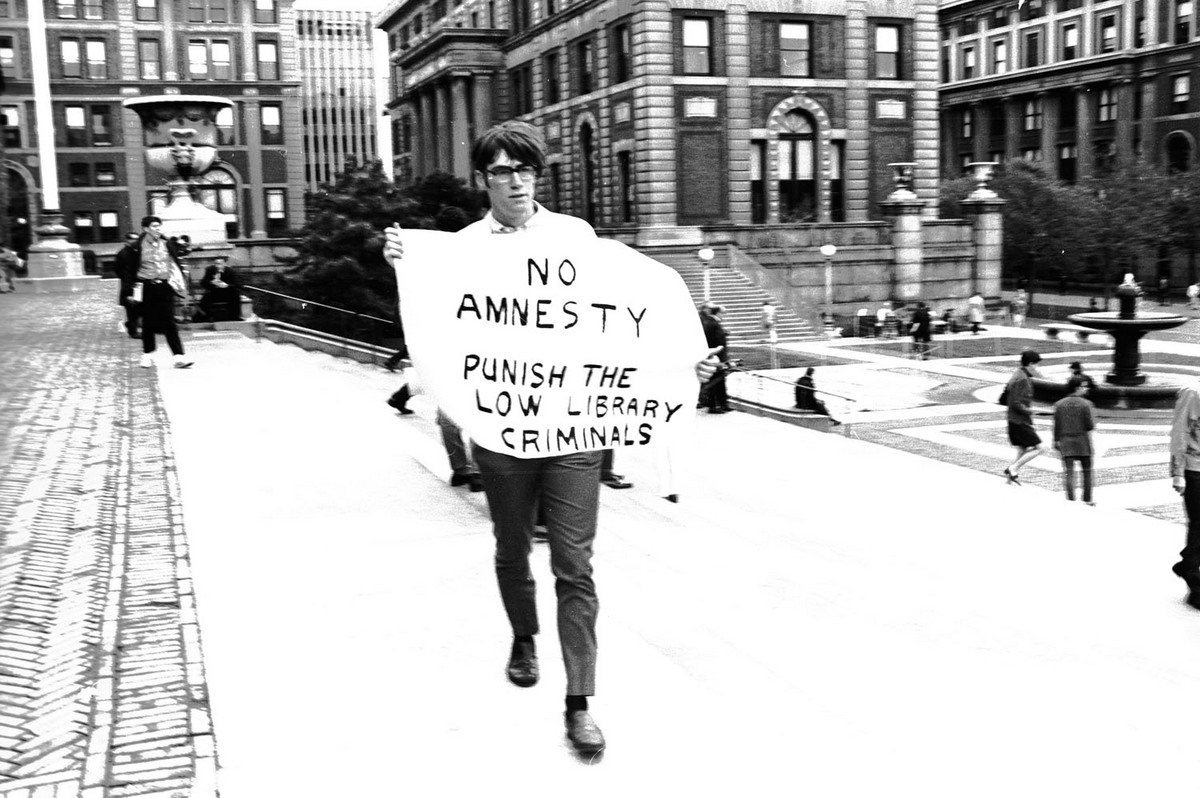

Anti-SDS student protesting against student occupation of buildings.

TUESDAY, April 30

TUESDAY, April 30

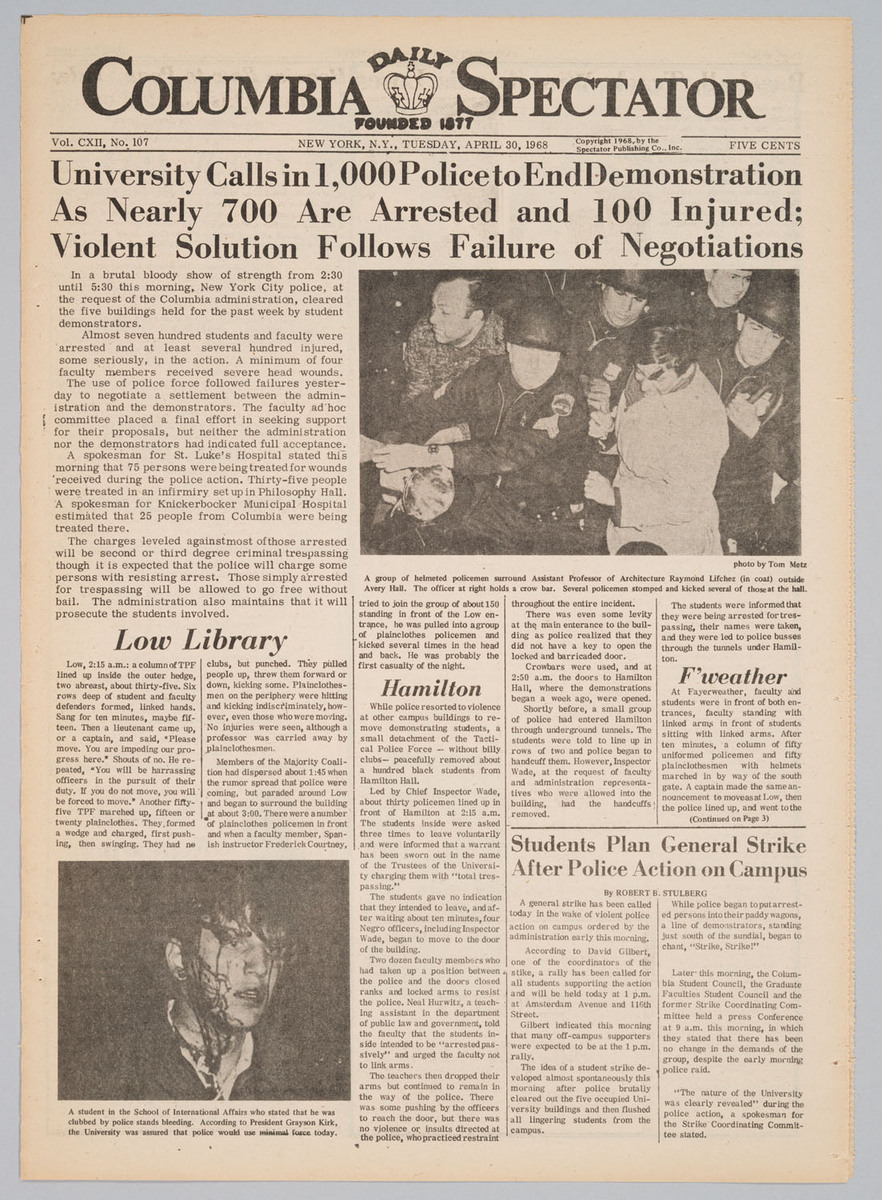

2:30 a.m. - 5:30 a.m. New York City police remove students from occupied buildings and clear campus; 712 arrested, 148 injured

Noon Ad Hoc. Faculty Group meets in McMillin Theatre to discuss a resolution in support of student strike; resolution presented and withdrawn

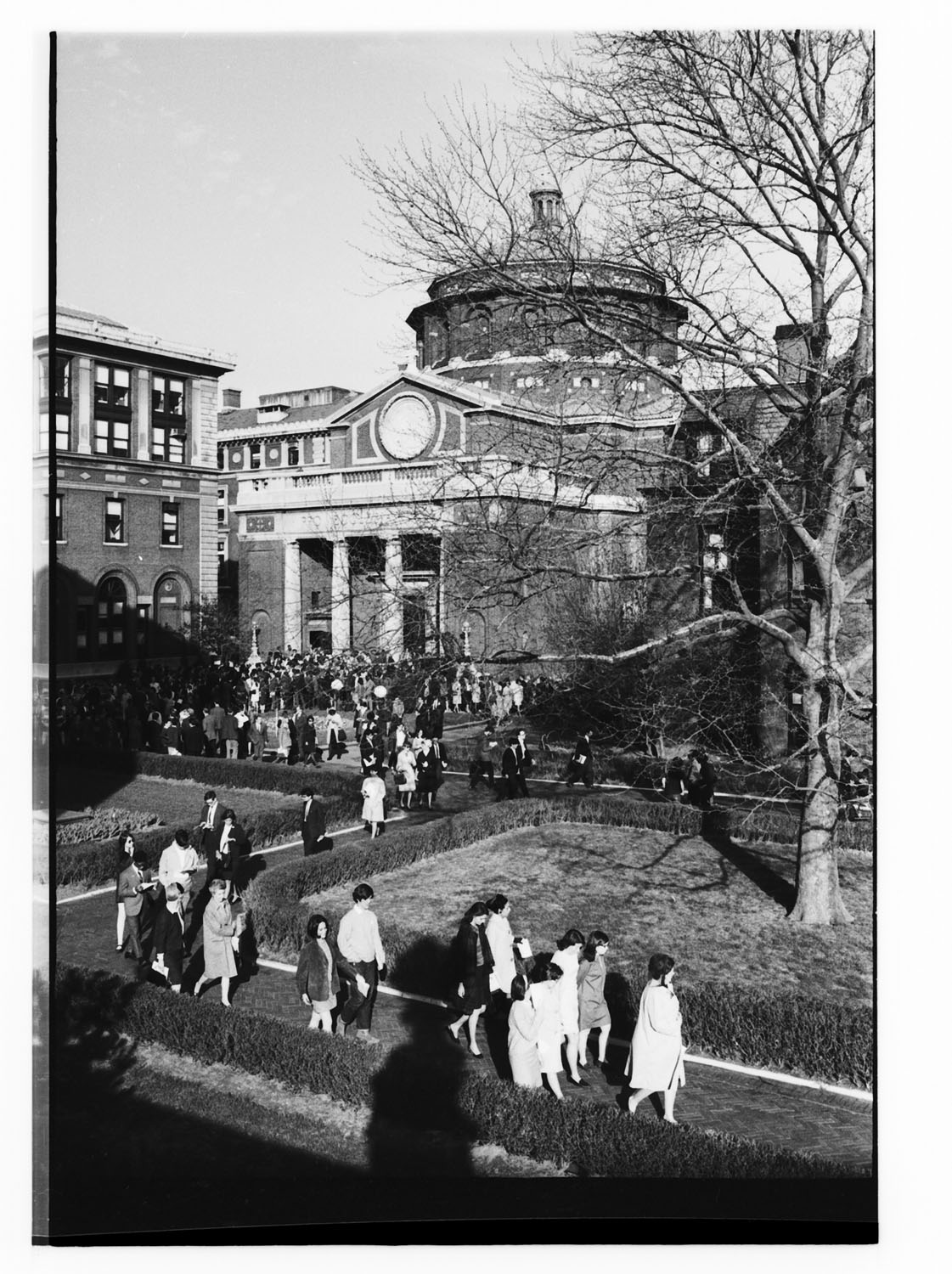

2:00 p.m. Joint Faculties meet in St. Paul's Chapel, establish Executive Committee of the Faculty

8:00 p.m. Students hold strike meeting in Wollman Auditorium

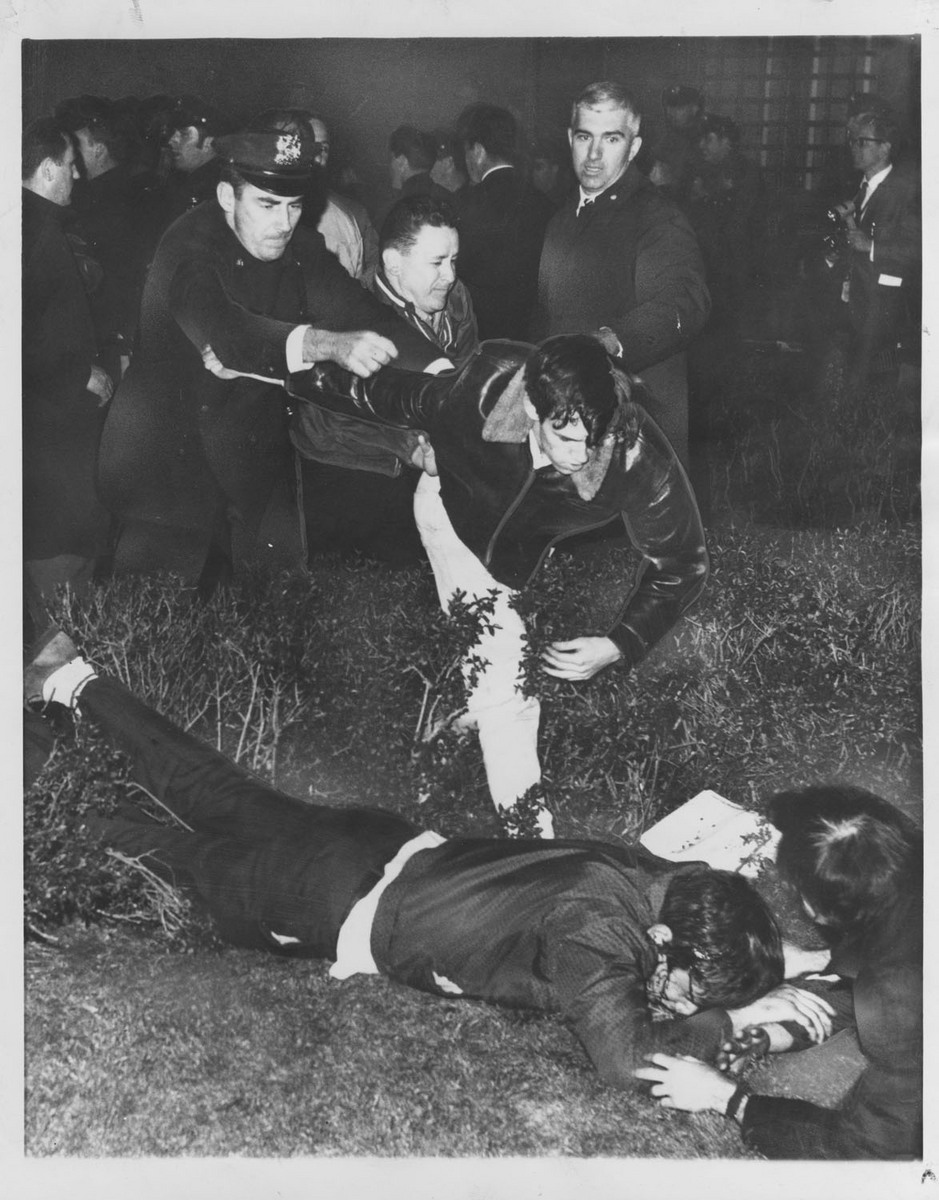

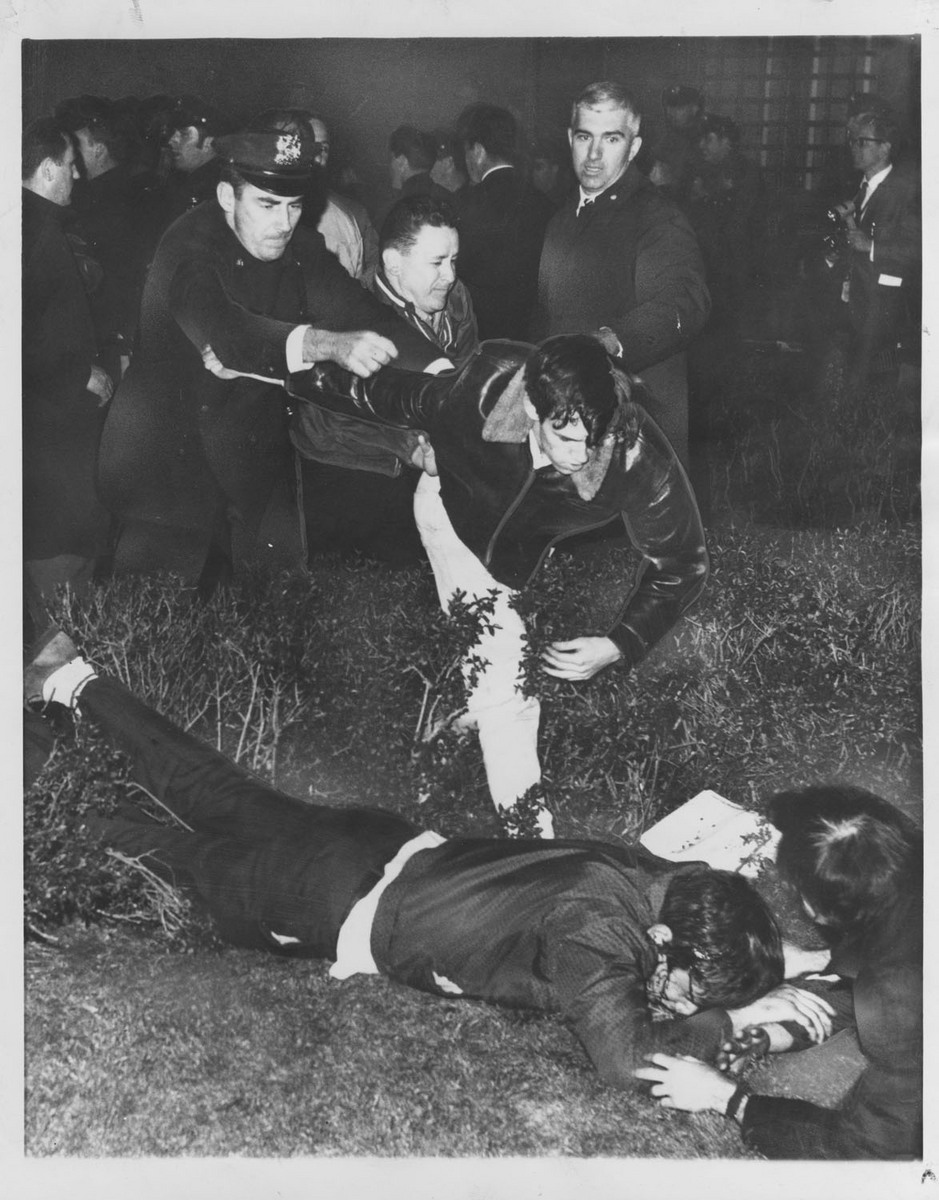

Police chasing students during the bust, April 30, 1968.

Photo courtesy of Paul Cronin, photographer unknown, 1968

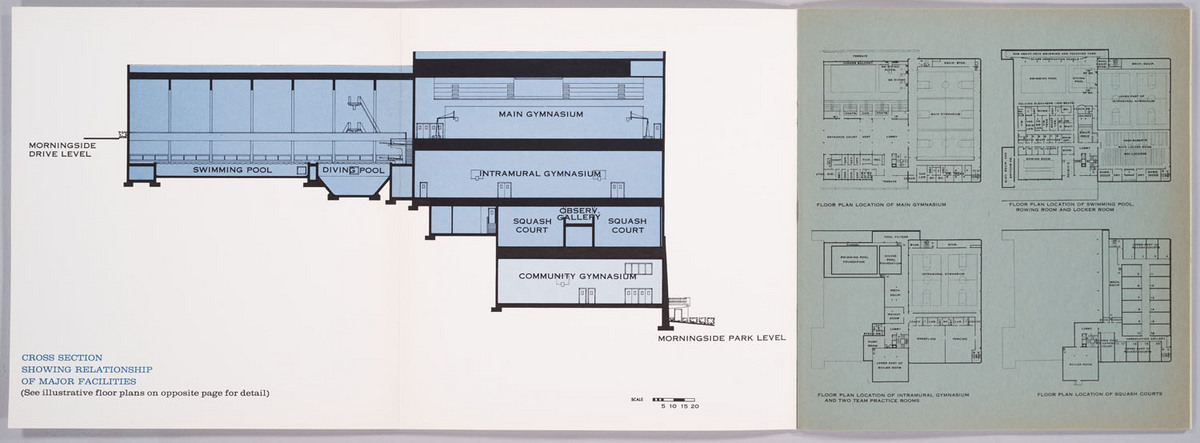

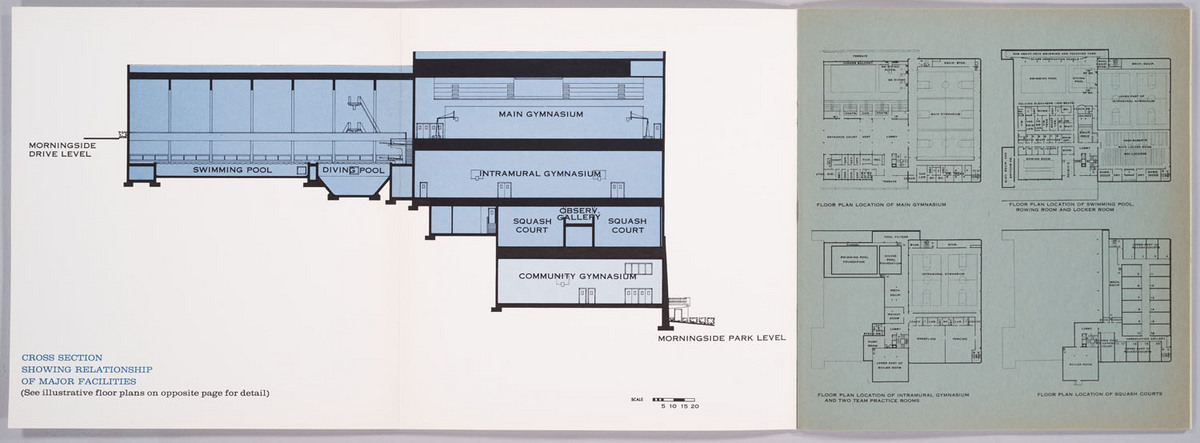

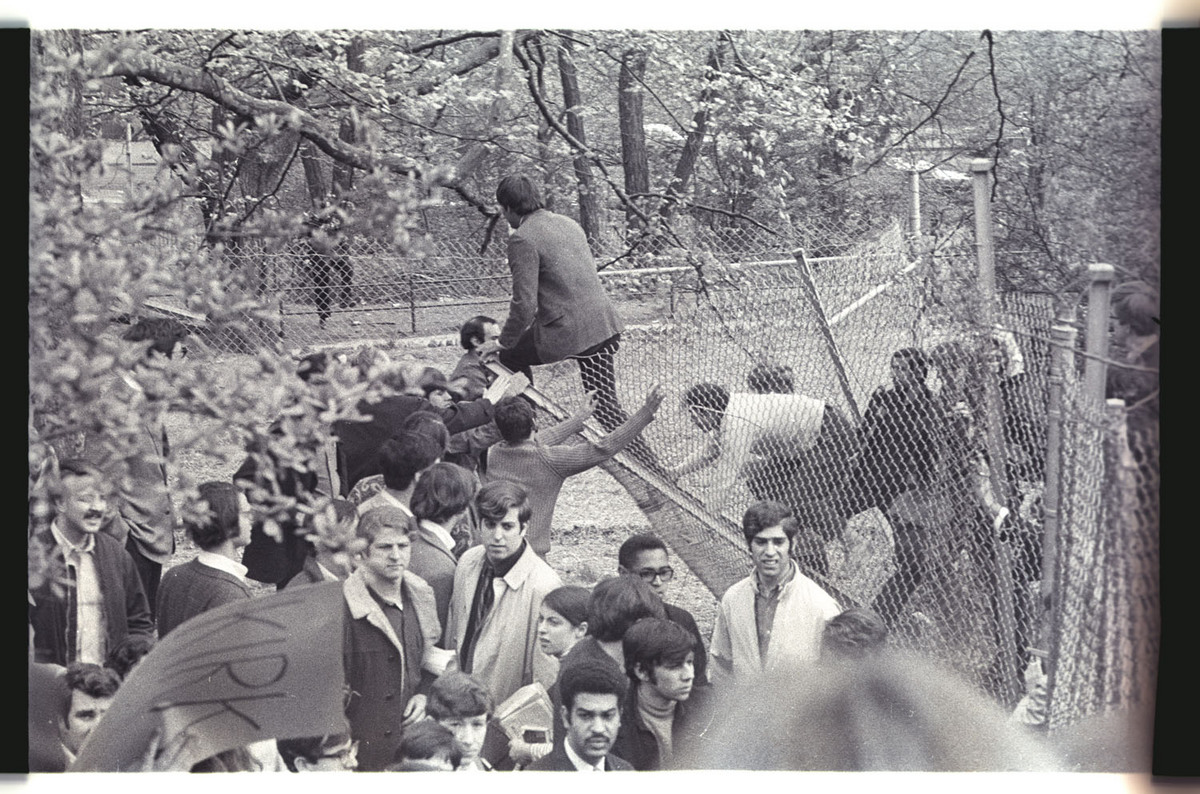

Brochure: "The New Gymnasium"

In 1959, at the urging of trustee Harold McGuire, the University initiated plans to build a gymnasium for Columbia College students that would sit on two acres of public land just inside Morningside Park. The New York Legislature approved Columbia’s gymnasium plans, which included limited community access, in 1960. Initially, this project boasted the support of the administration, the University trustees, College alumni, the local community, and government officials. Unfortunately, fundraising delays held up construction of the building for several years, allowing interested parties ample time to revise their opinions about the project. By the mid-1960s, the University’s allocation of public land for the project provoked increasingly negative feelings among government officials, community groups and Columbia students.

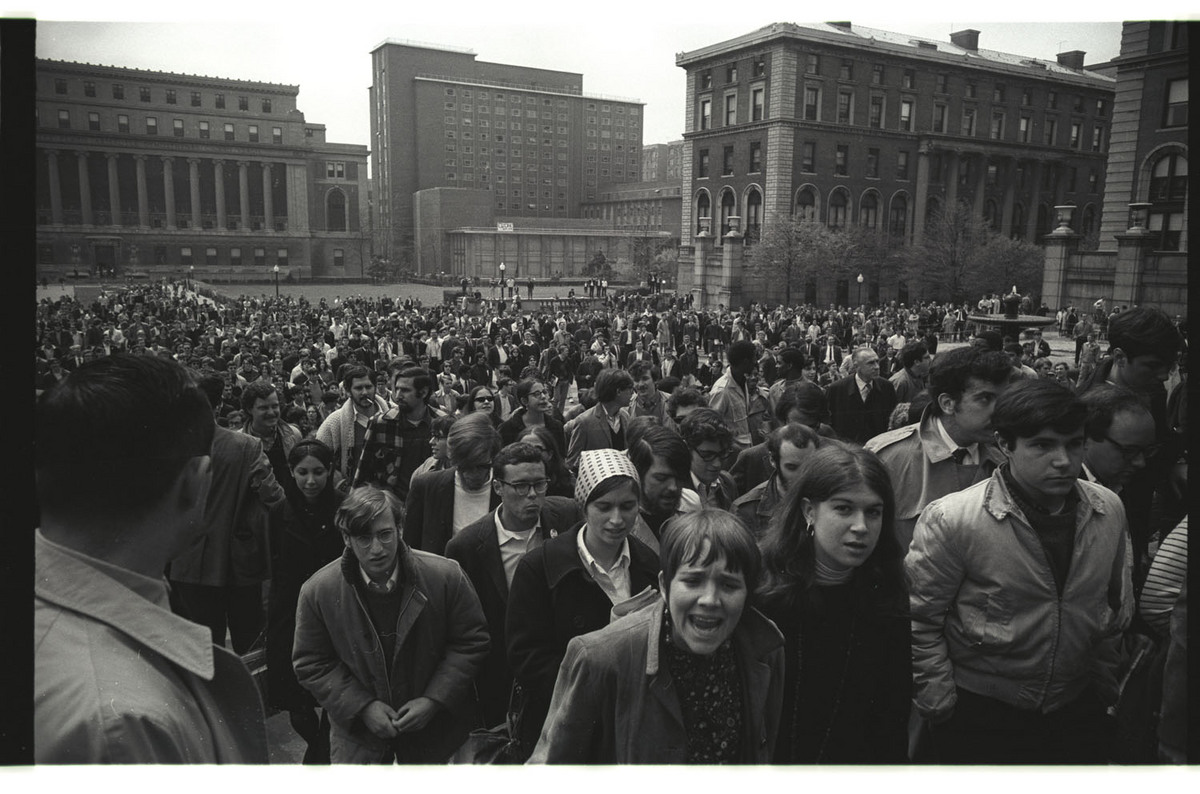

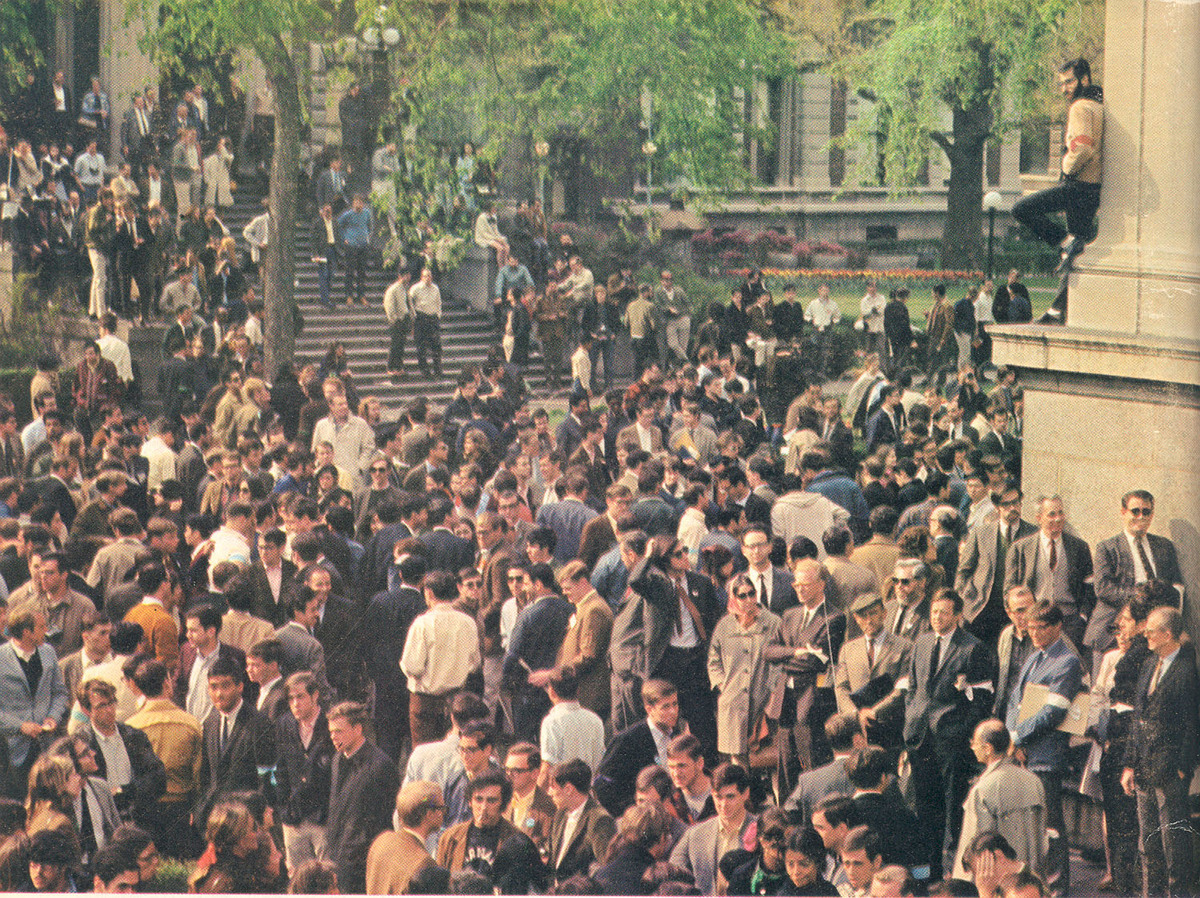

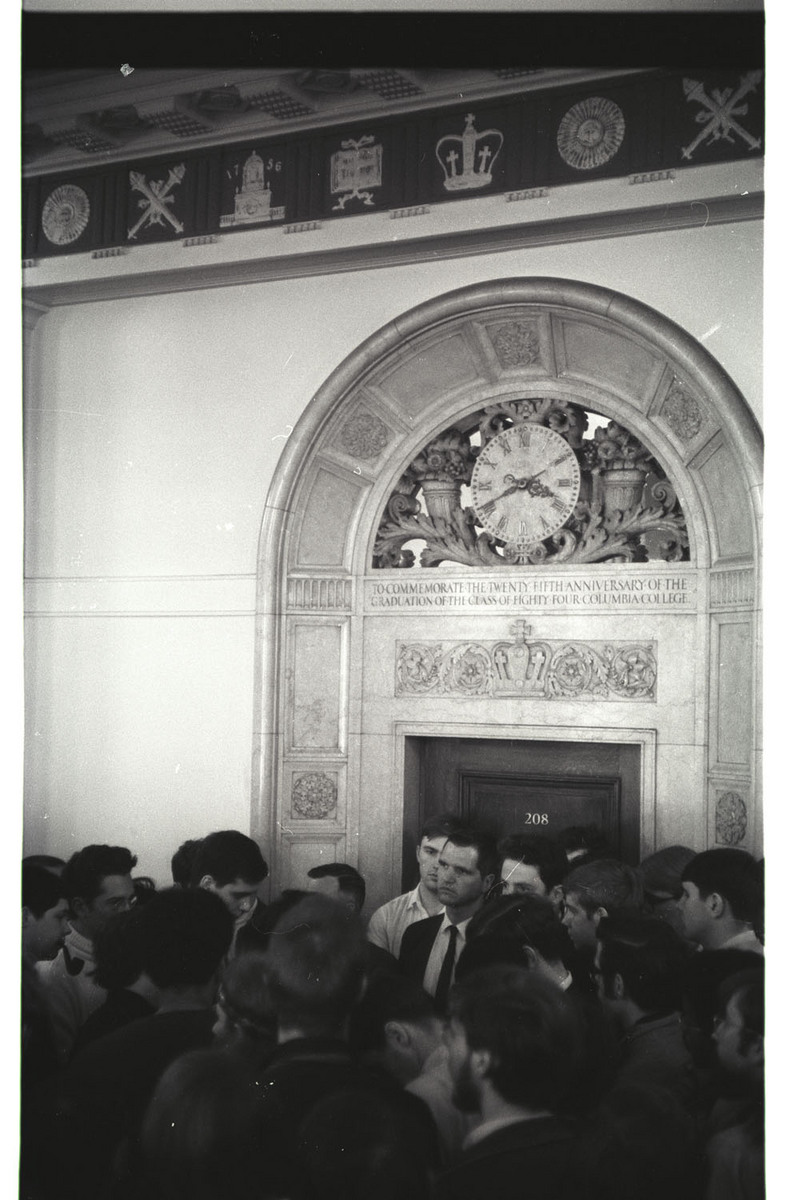

Crowds heading to Low Library

Crowd of people moving towards Low Library from Sun Dial Rally held on April 23, 1968

Original calendar of events

SDS Calendar Vol. II, no. 5. Typewritten calendar of events for the week of April 22, 1968 - before students knew they'd be taking over buildings that week.

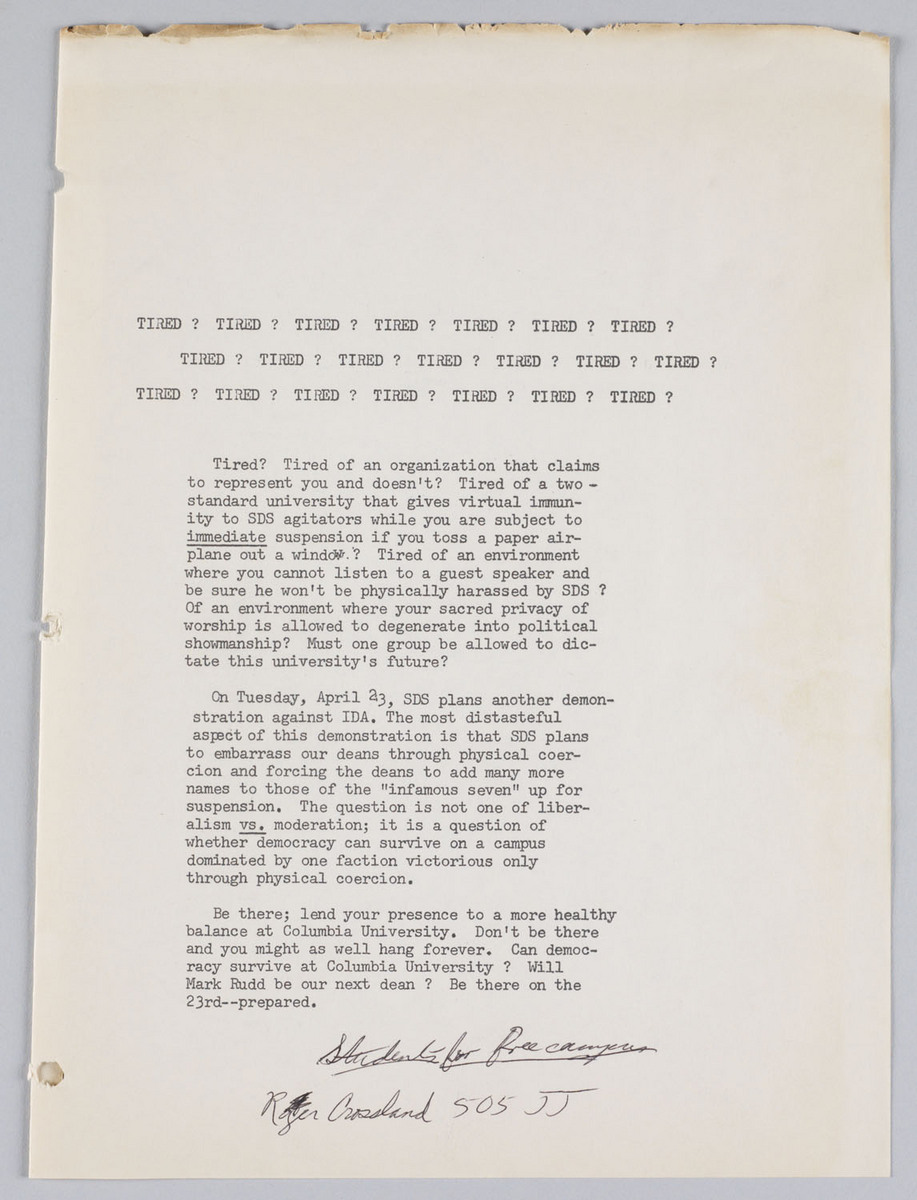

Circular: "Tired? Tired? Tired?"

Students for Free Campus announcing their counter-protest to the SDS sponsored rally at the Sun Dial on Tuesday, April 23, 1968. Typewritten circular.

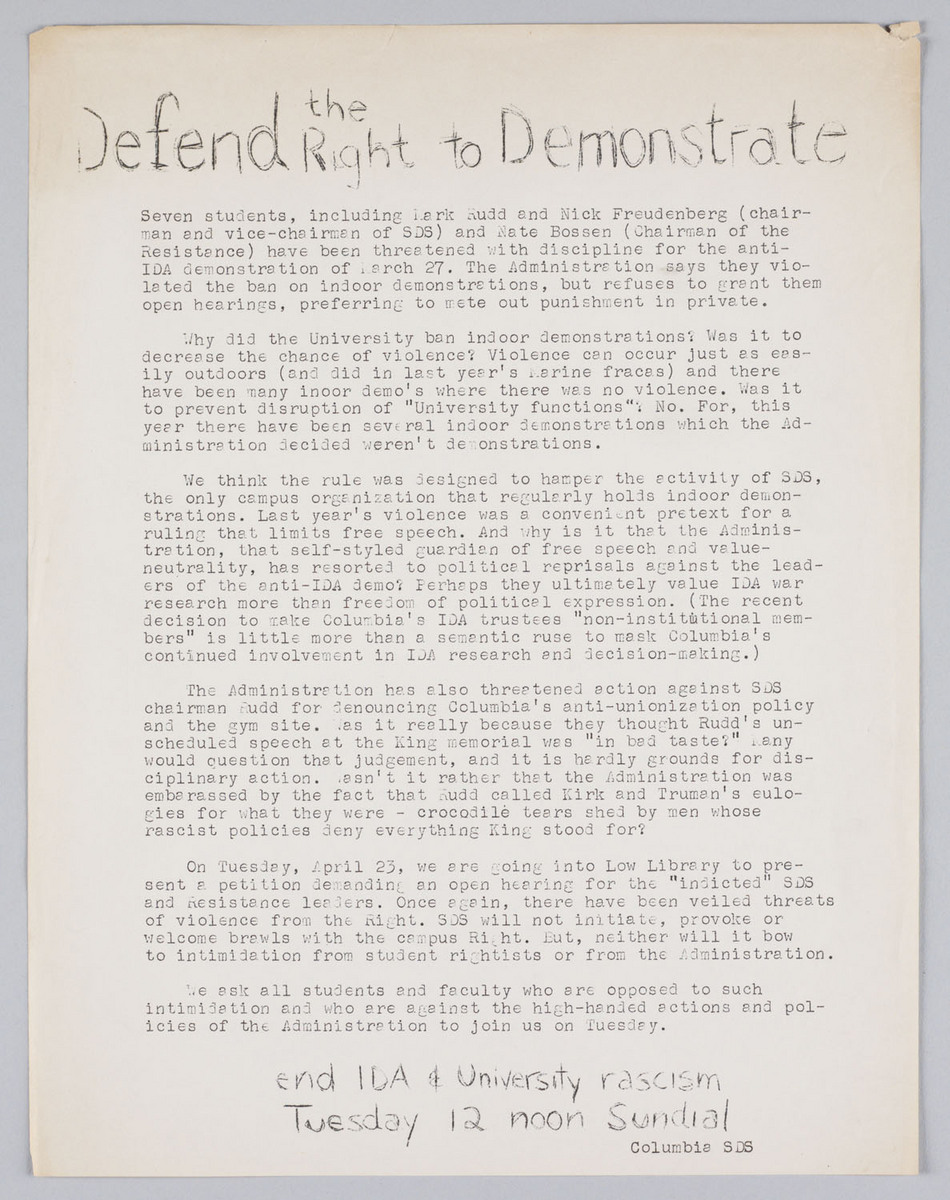

Defend the Right to Demonstrate

This SDS announcement of the April 23 Sun Dial Rally focuses on the fate of the "IDA Six", the right to indoor demonstrations and the right to free speech in response the administration's denouncing of Rudd's interruption at the MLK memorial service. SDS's early agenda did not prioritize termininating the Morningside Park Gymnasium construction.

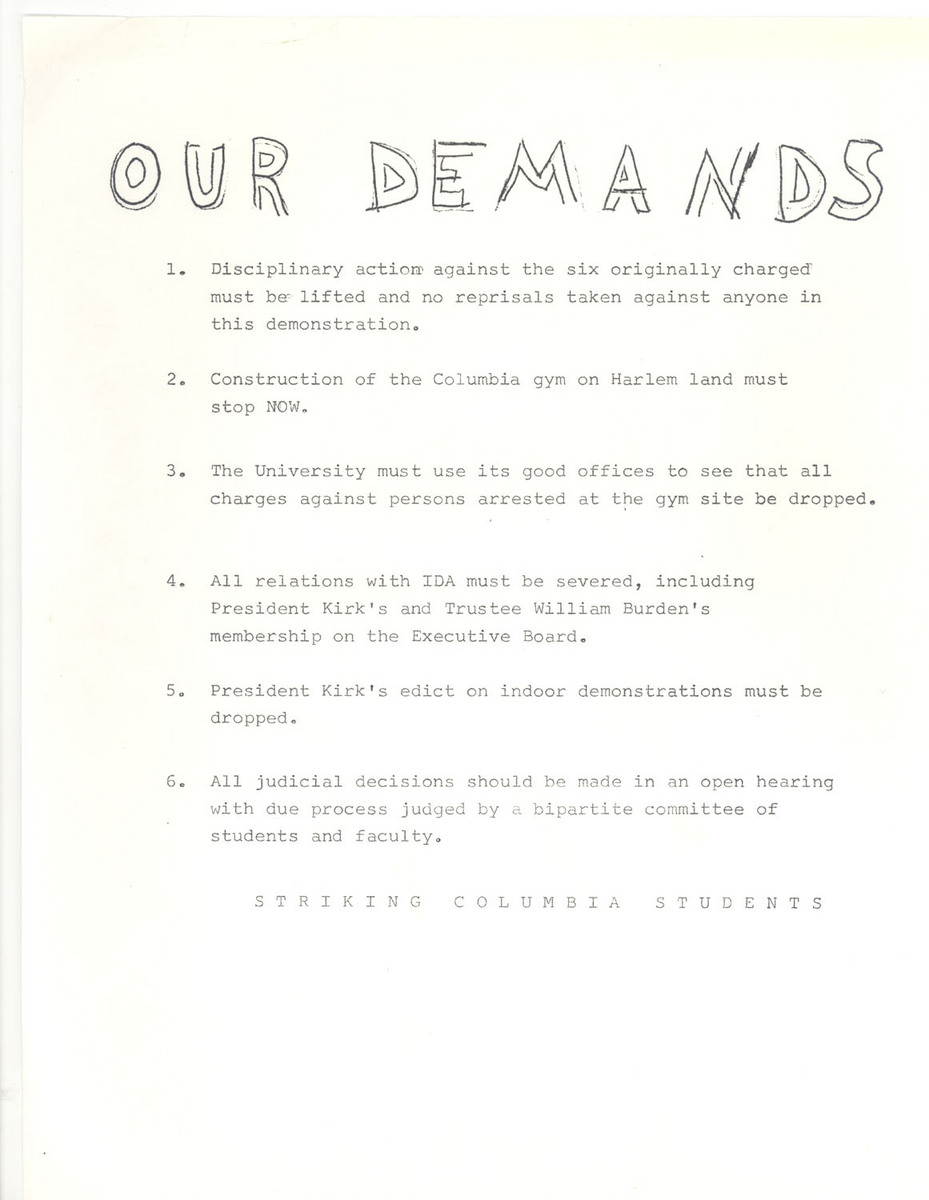

Our Demands

A listing the six demands of the striking students who had occupied Hamilton Hall on the first day of the protests.

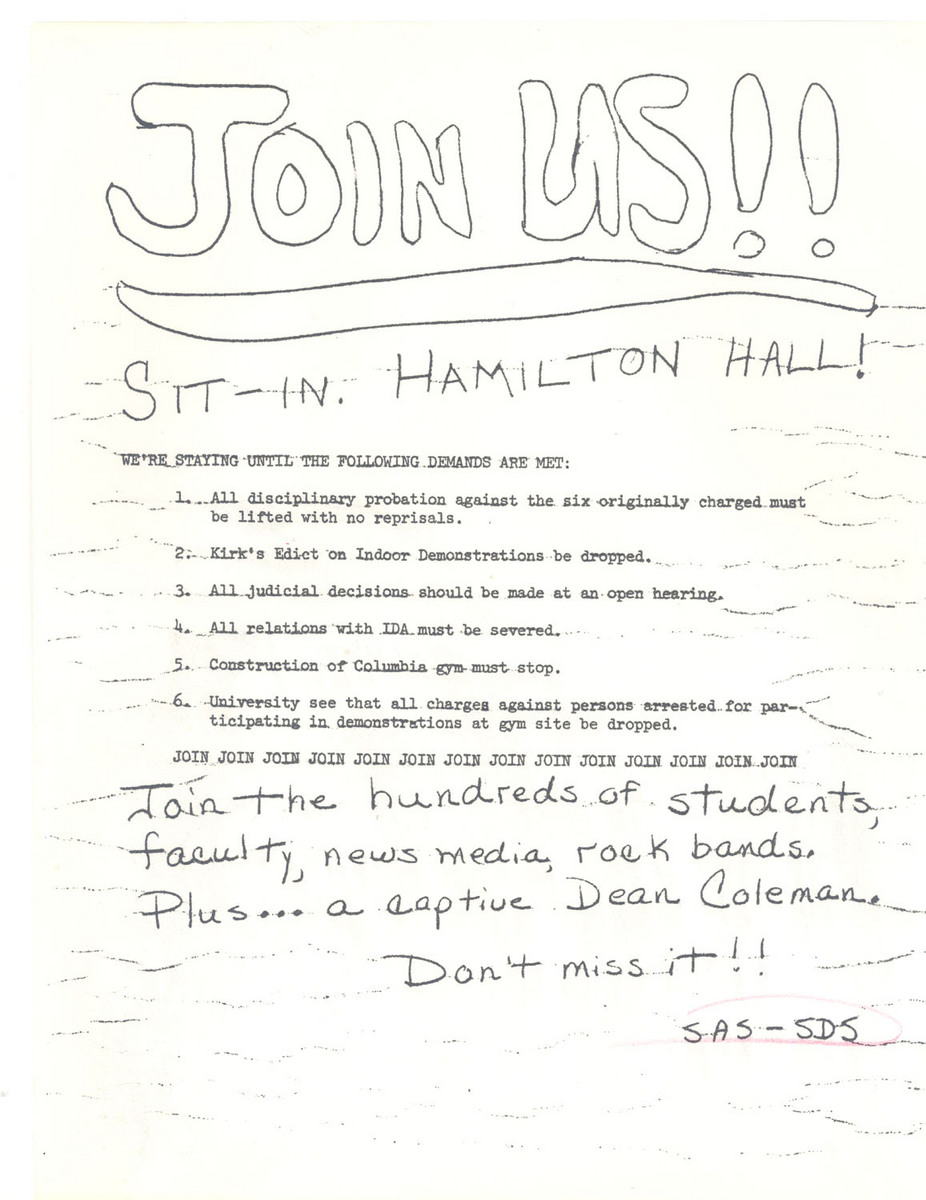

Join Us!

Late in the day on April 23, Black and White students in Hamilton Hall listed their six demands and made reference to "a captive Dean Coleman."

Dean Henry Coleman

Dean Henry Coleman speaking with the protesting students holding him captive in Hamilton Hall, April 23, 1968.

Brochure: "The New Gymnasium"

In 1959, at the urging of trustee Harold McGuire, the University initiated plans to build a gymnasium for Columbia College students that would sit on two acres of public land just inside Morningside Park. The New York Legislature approved Columbia’s gymnasium plans, which included limited community access, in 1960. Initially, this project boasted the support of the administration, the University trustees, College alumni, the local community, and government officials. Unfortunately, fundraising delays held up construction of the building for several years, allowing interested parties ample time to revise their opinions about the project. By the mid-1960s, the University’s allocation of public land for the project provoked increasingly negative feelings among government officials, community groups and Columbia students.

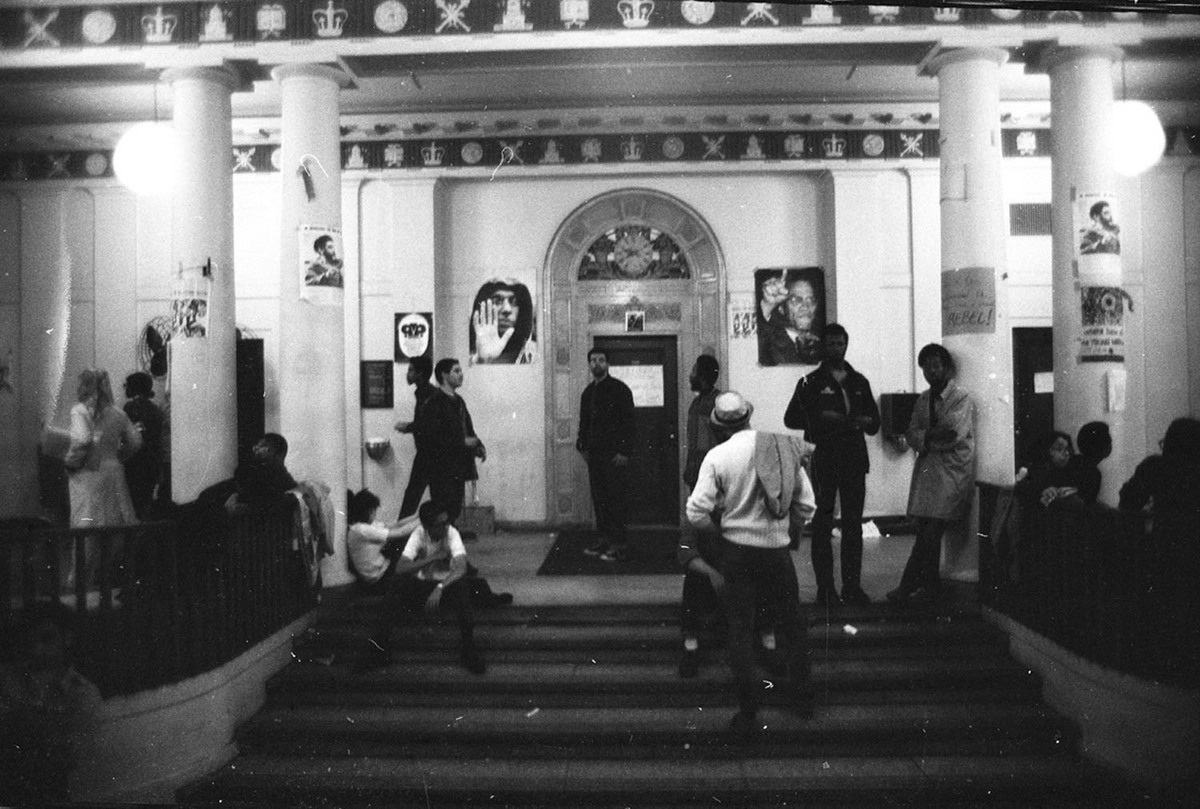

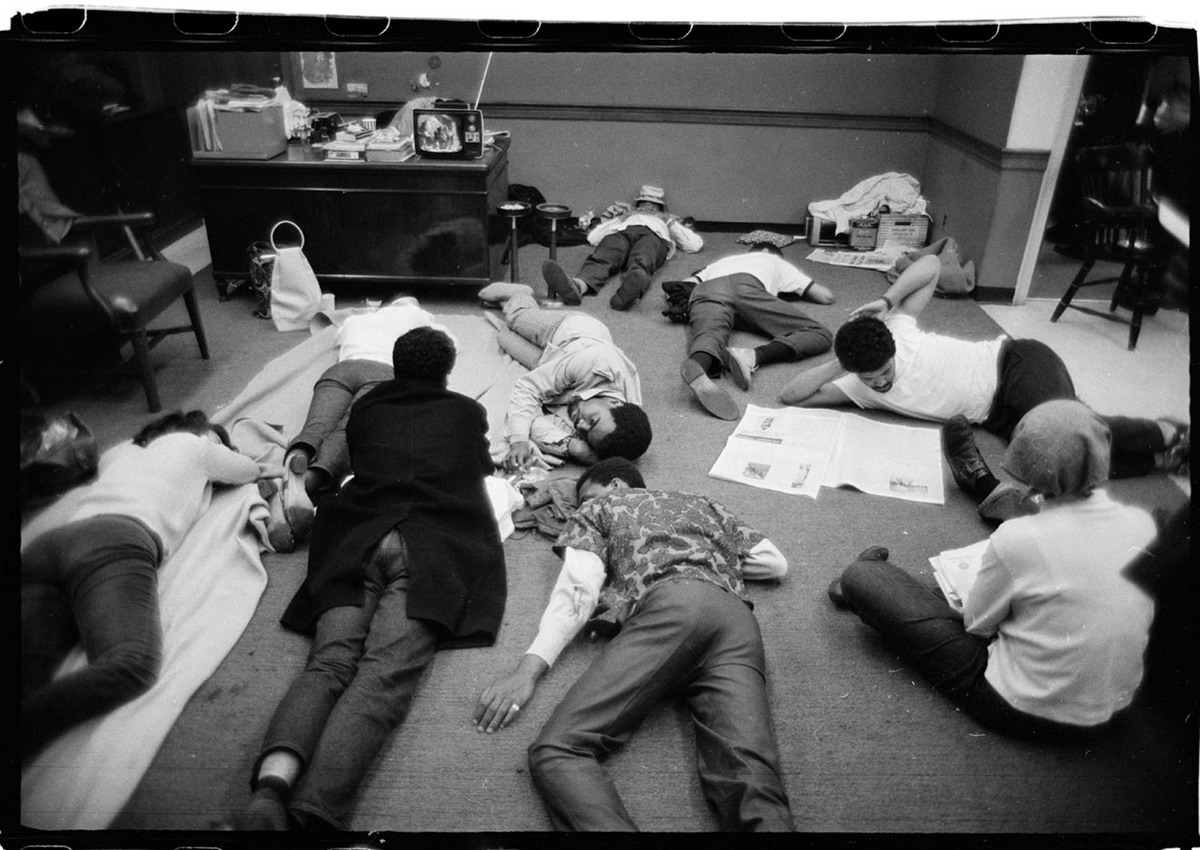

Interior of Hamilton Hall during the occupation.

Interior of Hamilton Hall during the occupation This image may not be reproduced. Please contact the University Archives with any questions.

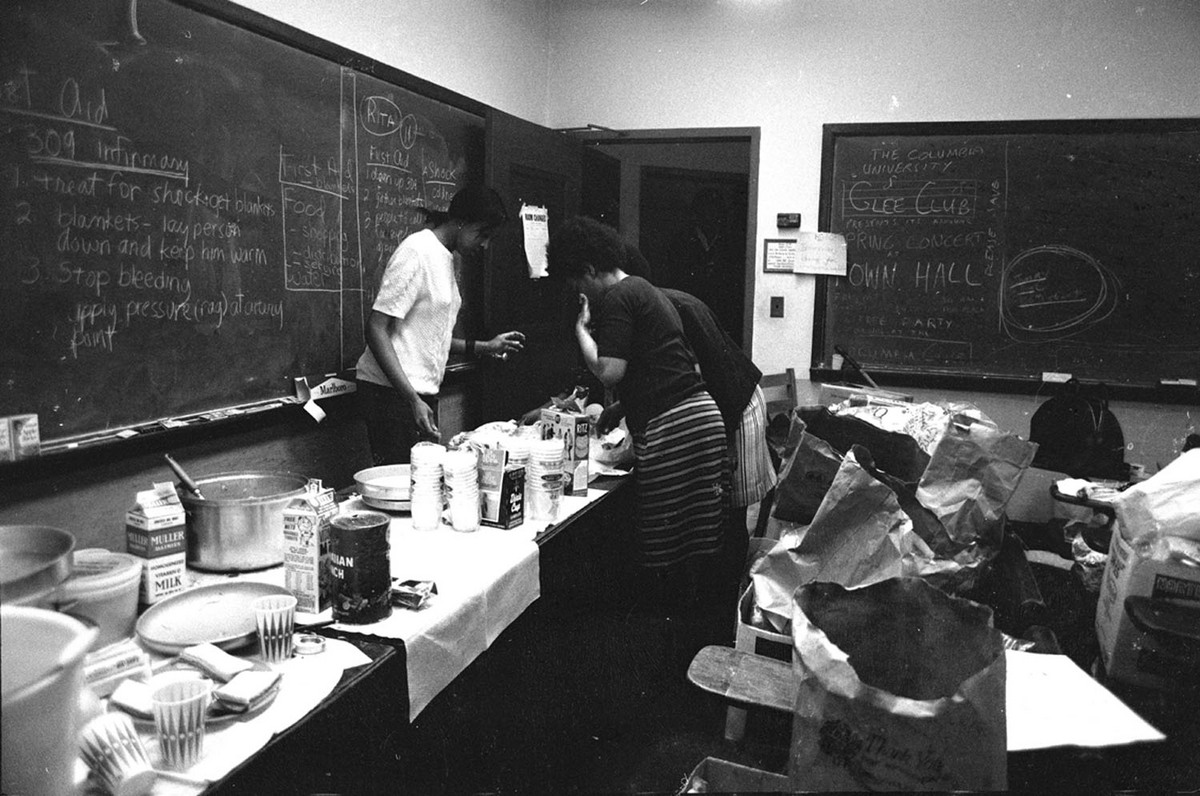

Food pantry inside Hamilton Hall during the occupation.

Throughout the last week of April, the black students occupying Hamilton developed an organized, tight-knit, and disciplined community, one that differed sharply from the more boisterous atmosphere of other occupied buildings such as Mathematics. To the administration, however, the black-occupied building appeared a time bomb; Kirk, Truman and the trustees feared that the forcible removal of the SAS students in Hamilton would generate a violent reaction from the nearby Harlem community. This fear helps to explain why the administration waited a week before calling in the police to clear the campus. In fact, when the police entered barricaded Hamilton Hall in the early hours of April 30, the occupying students avoided struggles with the police, calmly marched out the main entrance of the building to the police vans waiting on College Walk.

Students inside occupied Hamilton Hall

This image may not be reproduced. Please contact the University Archives with any questions.

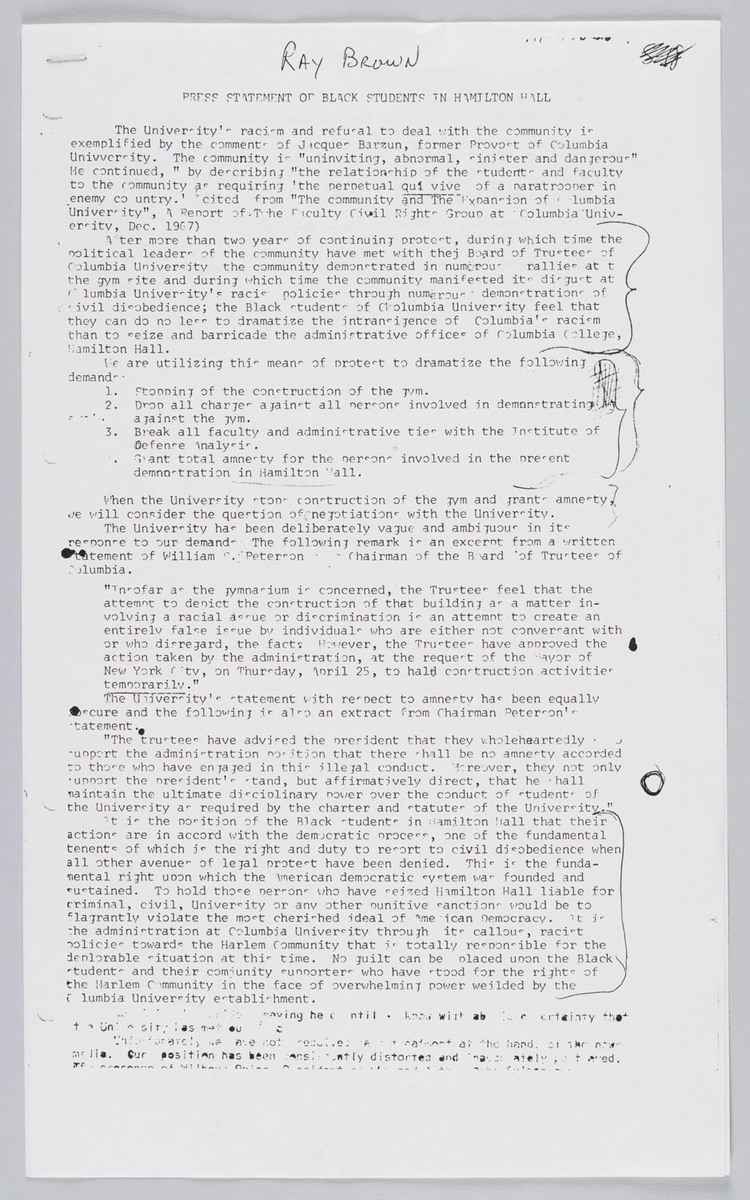

Dean, Alex B. Platt to Columbia University students in Hamilton Hall

The black students occupying Hamilton Hall rejected the administration's early efforts at compromise. This correspondence concerns disciplinary probation for those occupying Hamilton Hall.

H. Rap Brown reading Hamilton Hall statement

Permission to reproduce this image must be obtained from Lee T. Pearcy. Please contact the University Archives for contact information.

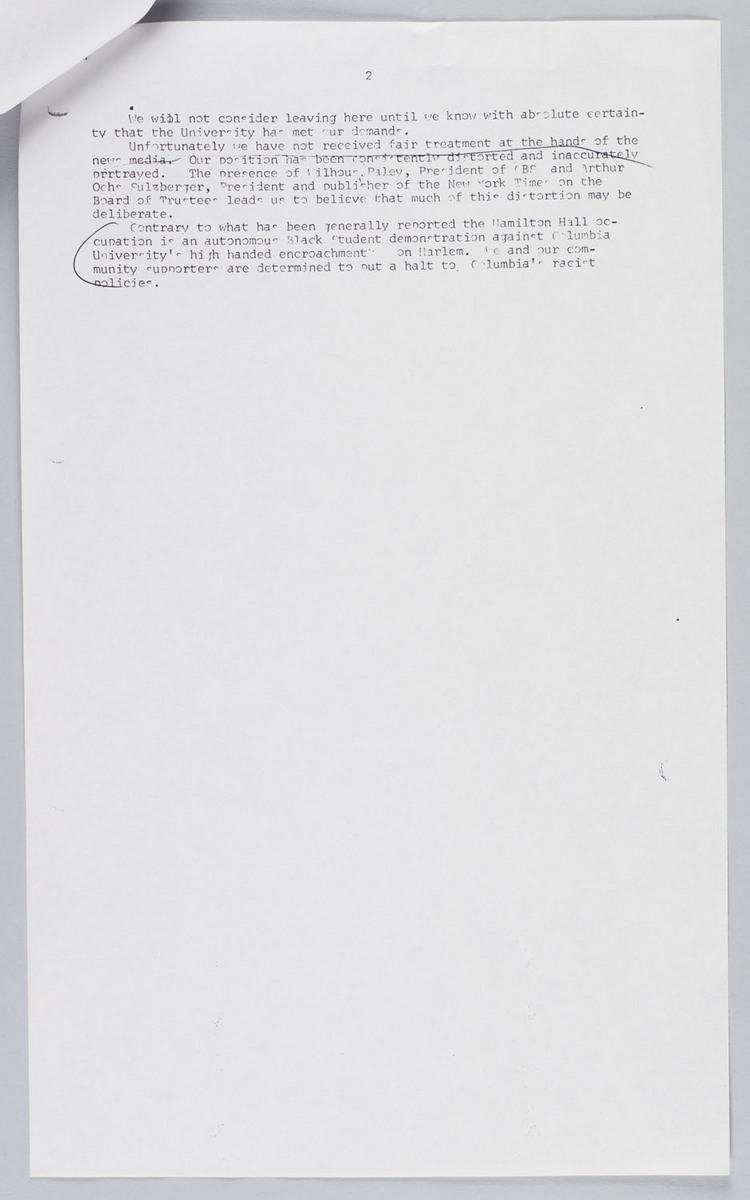

Statement from black students occupying Hamilton Hall

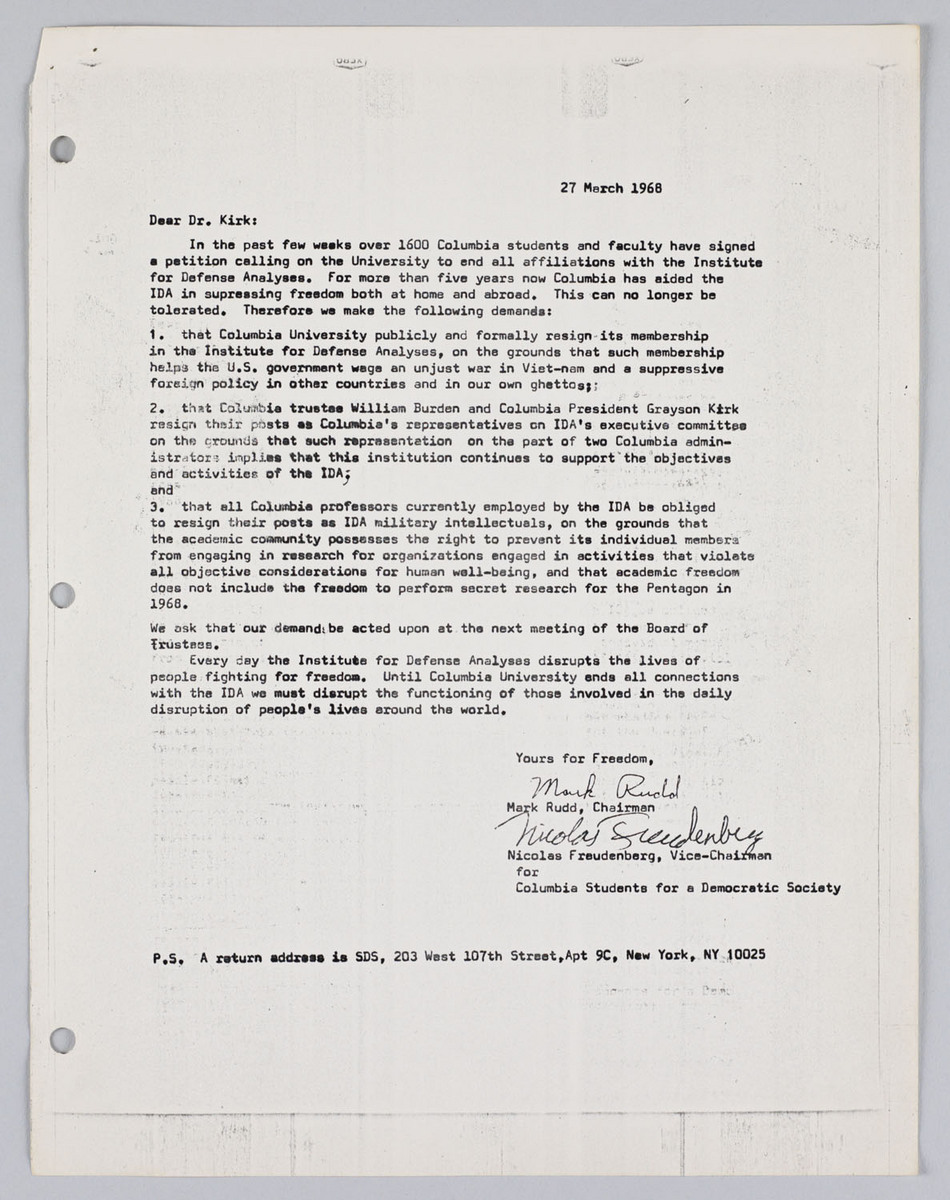

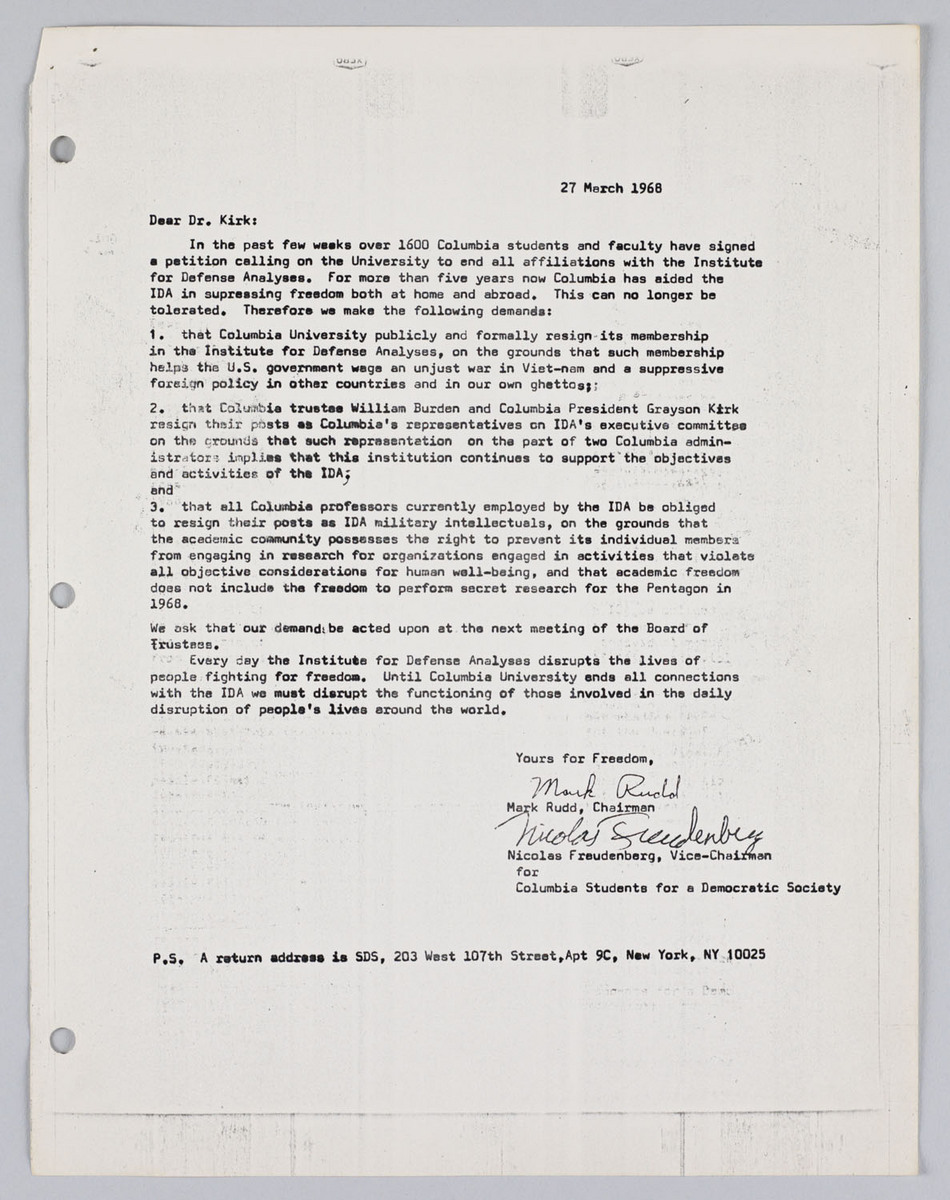

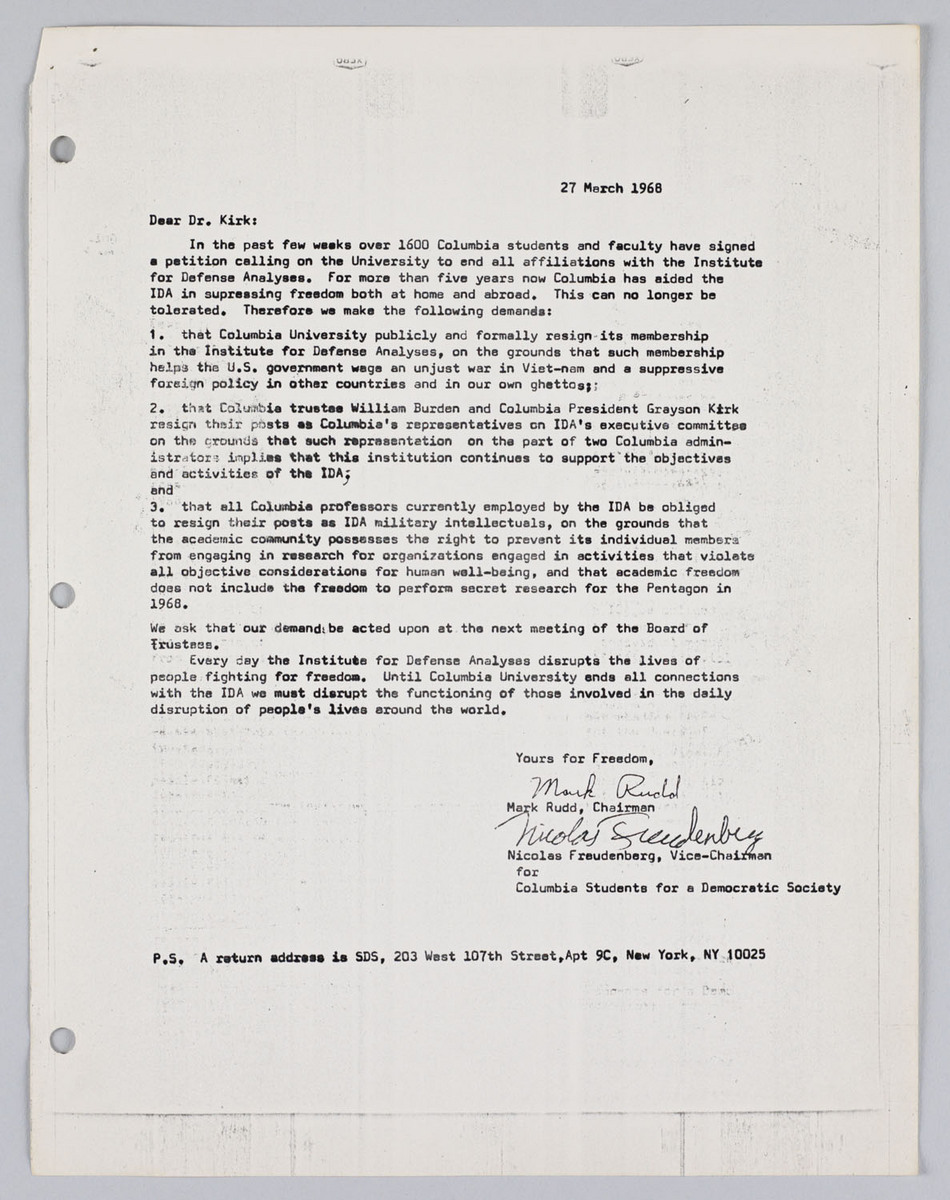

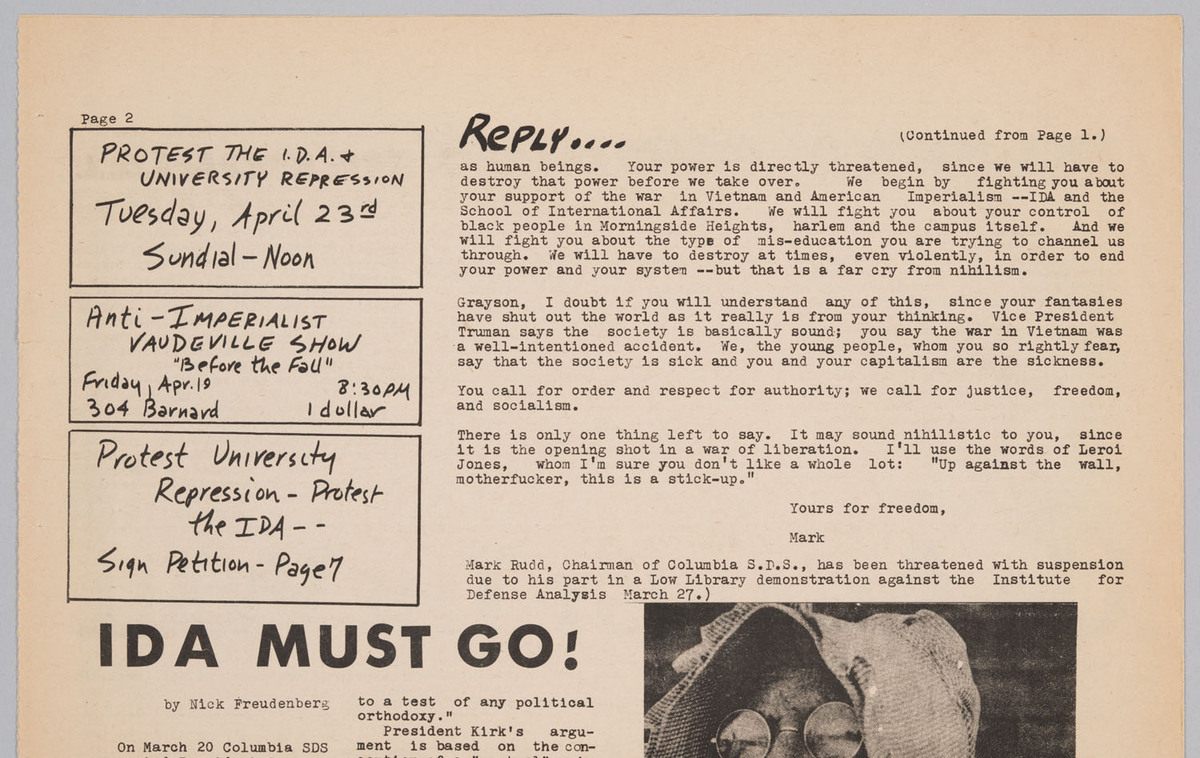

Letter from Rudd and Freudenberg to Kirk

In 1959, Columbia joined the five-year old Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), and University president Grayson Kirk became Columbia’s representative on the IDA board. IDA served as a forum where leading research universities and government agencies that funded military research could discuss issues of mutual interest. Although IDA did not issue contracts for military research and development, participating members were given de facto priority. Columbia acknowledged its membership in IDA when questioned by SDS in the mid-1960s, but proved less forthcoming about the extent of defense-related secret research conducted at the University. President Kirk refused to consider allowing the faculty to vote on the issue of withdrawal from the IDA when other universities, including Princeton and University of Chicago, were doing just that. In response to growing criticism of Columbia’s involvement in IDA Kirk created the Henkin Committee in January 1968 to investigate the University’s ties to the defense industry.

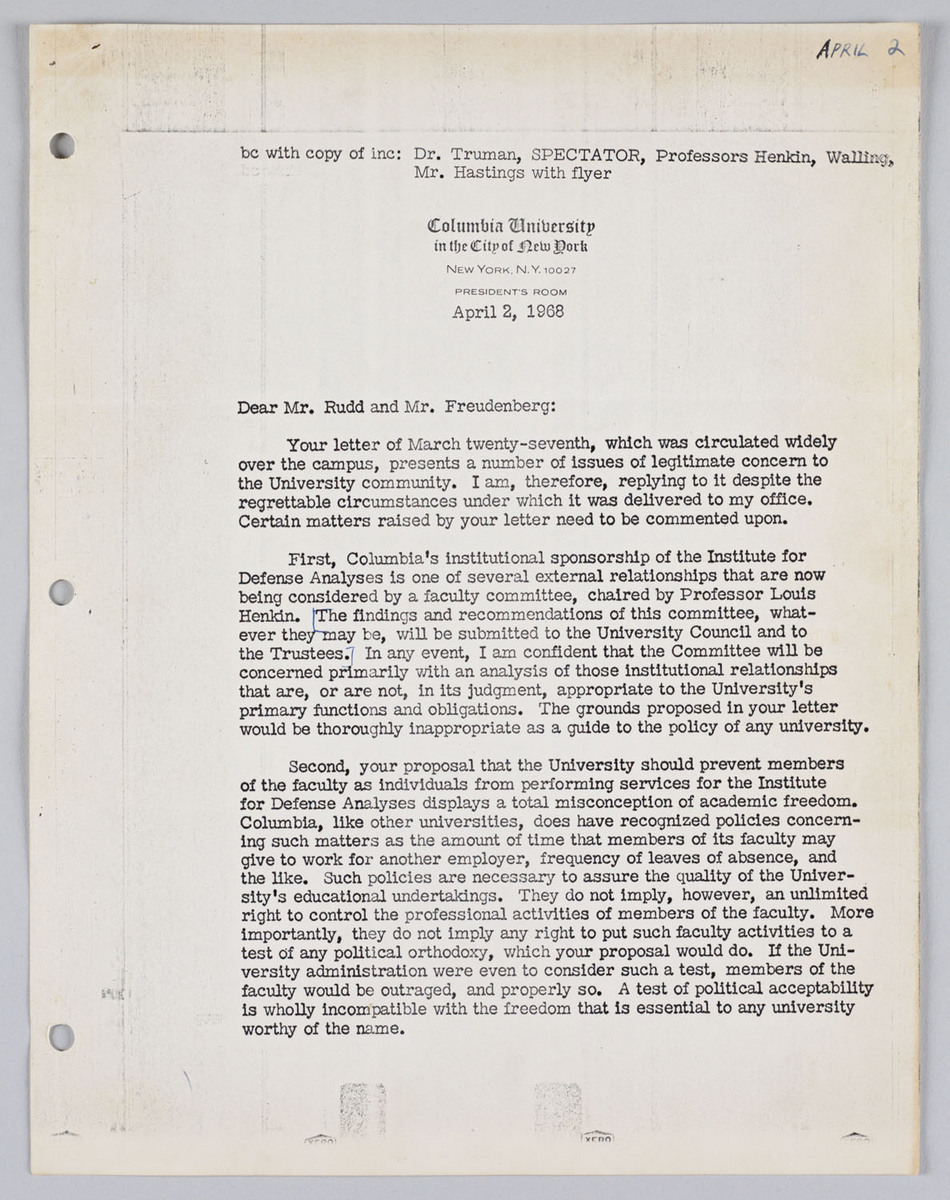

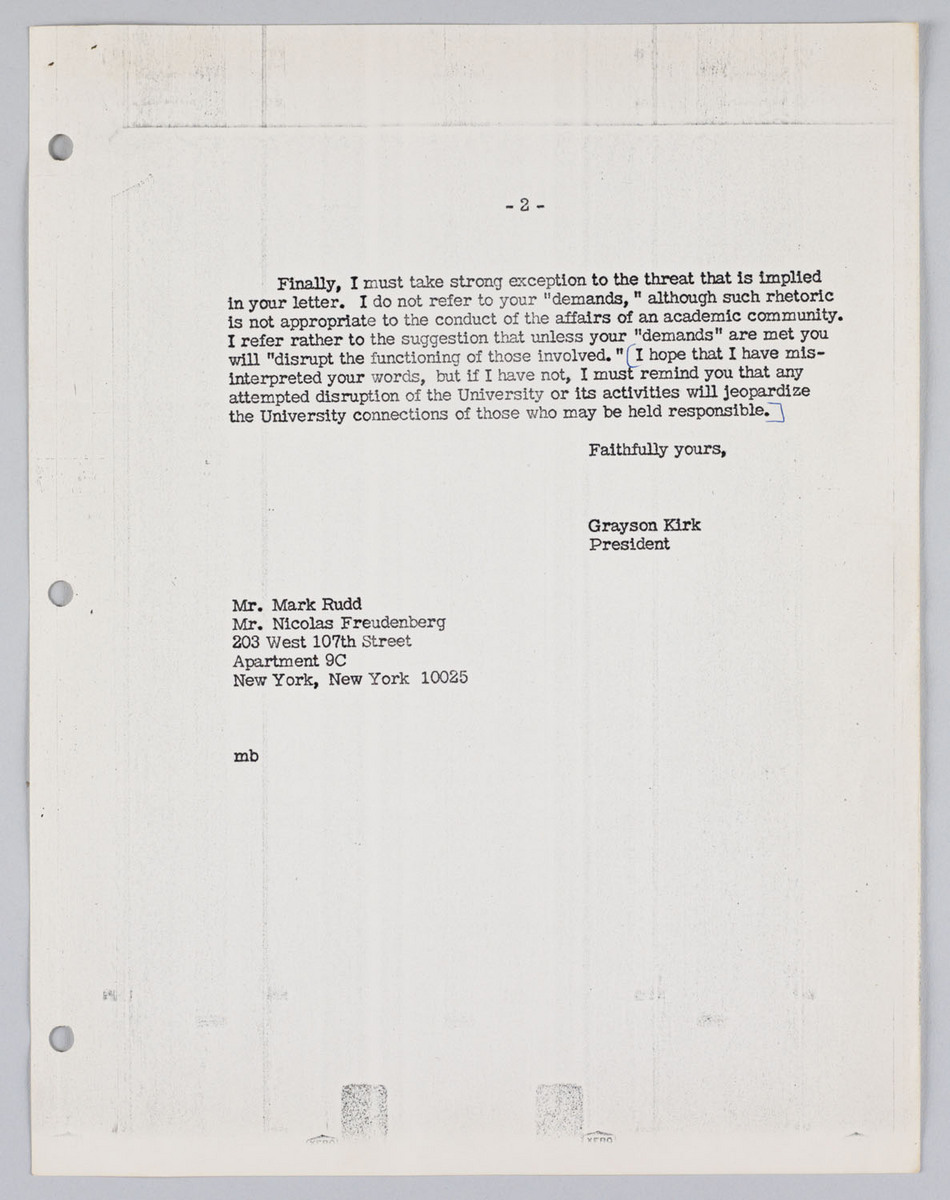

April 2, 1968 letter from President Kirk in response to Rudd and Freudenberg.

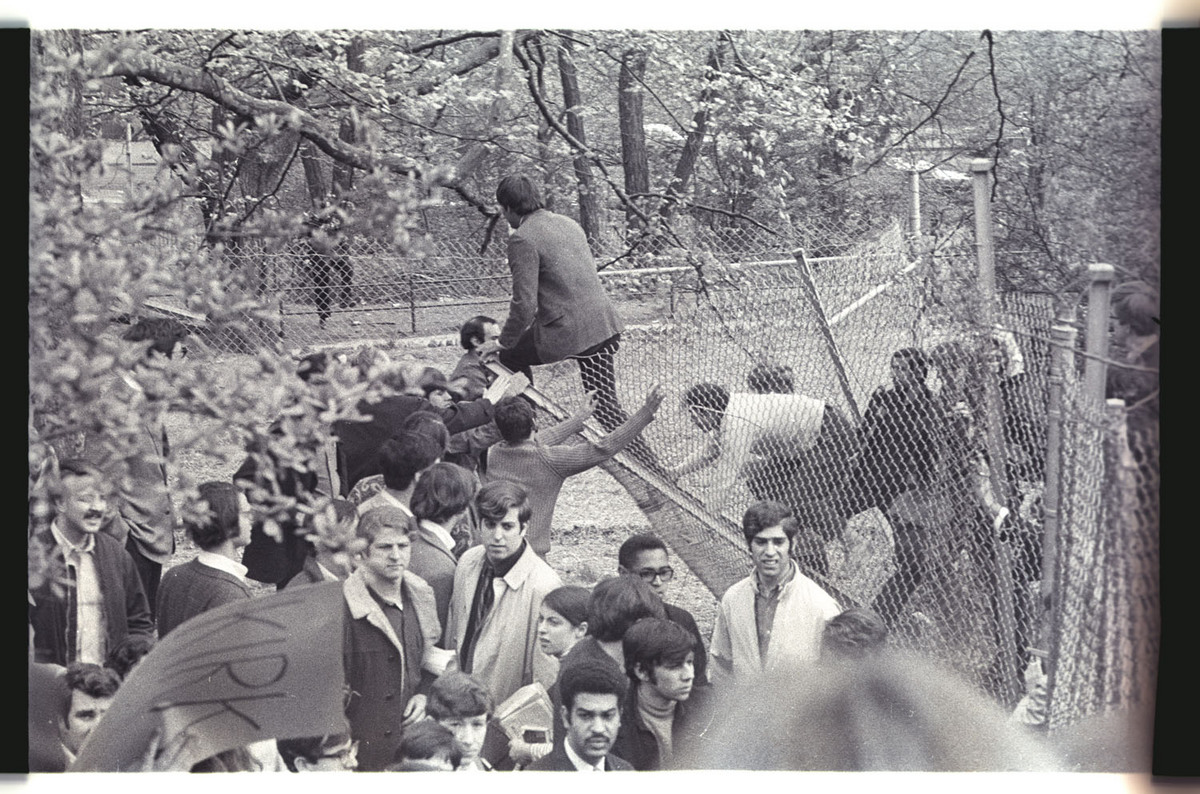

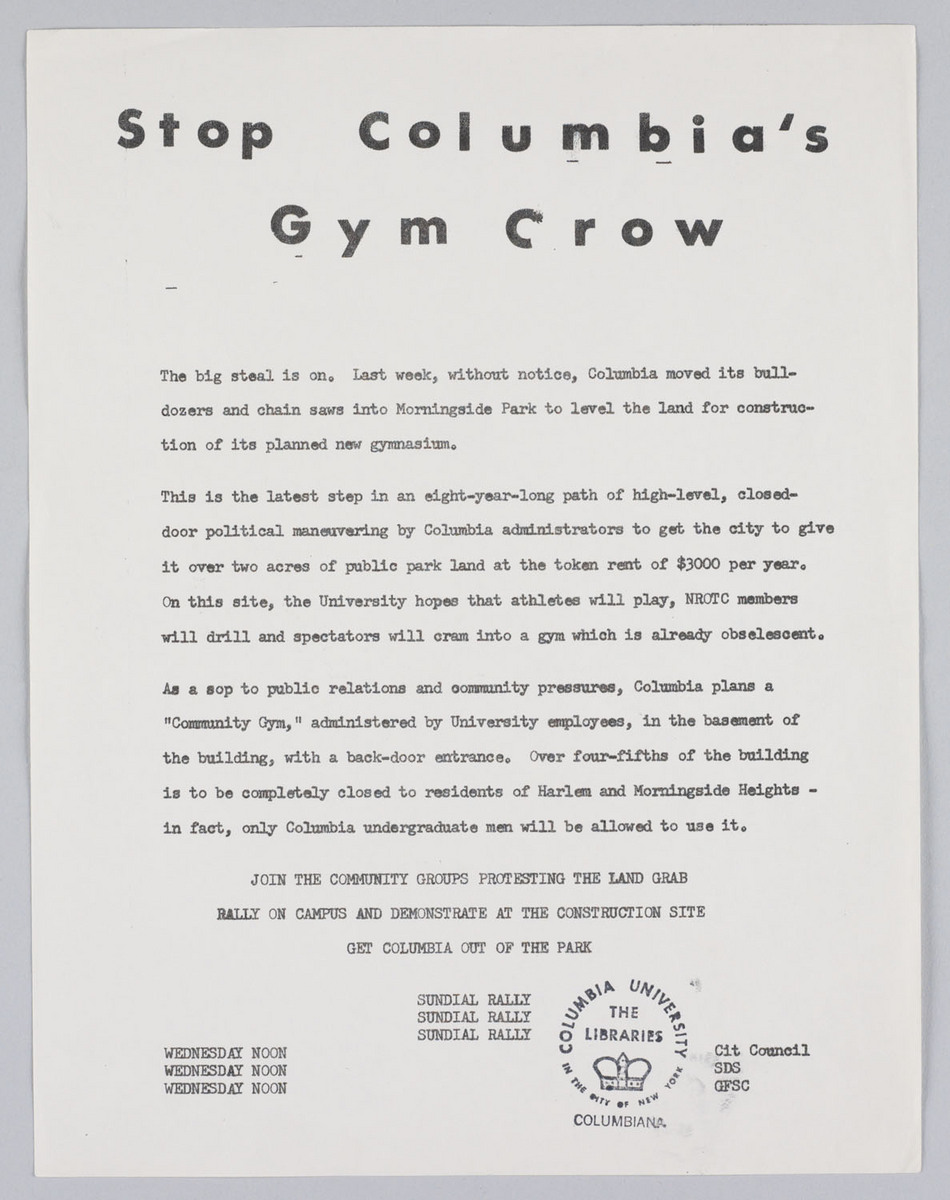

Protestors tearing down protective fencing

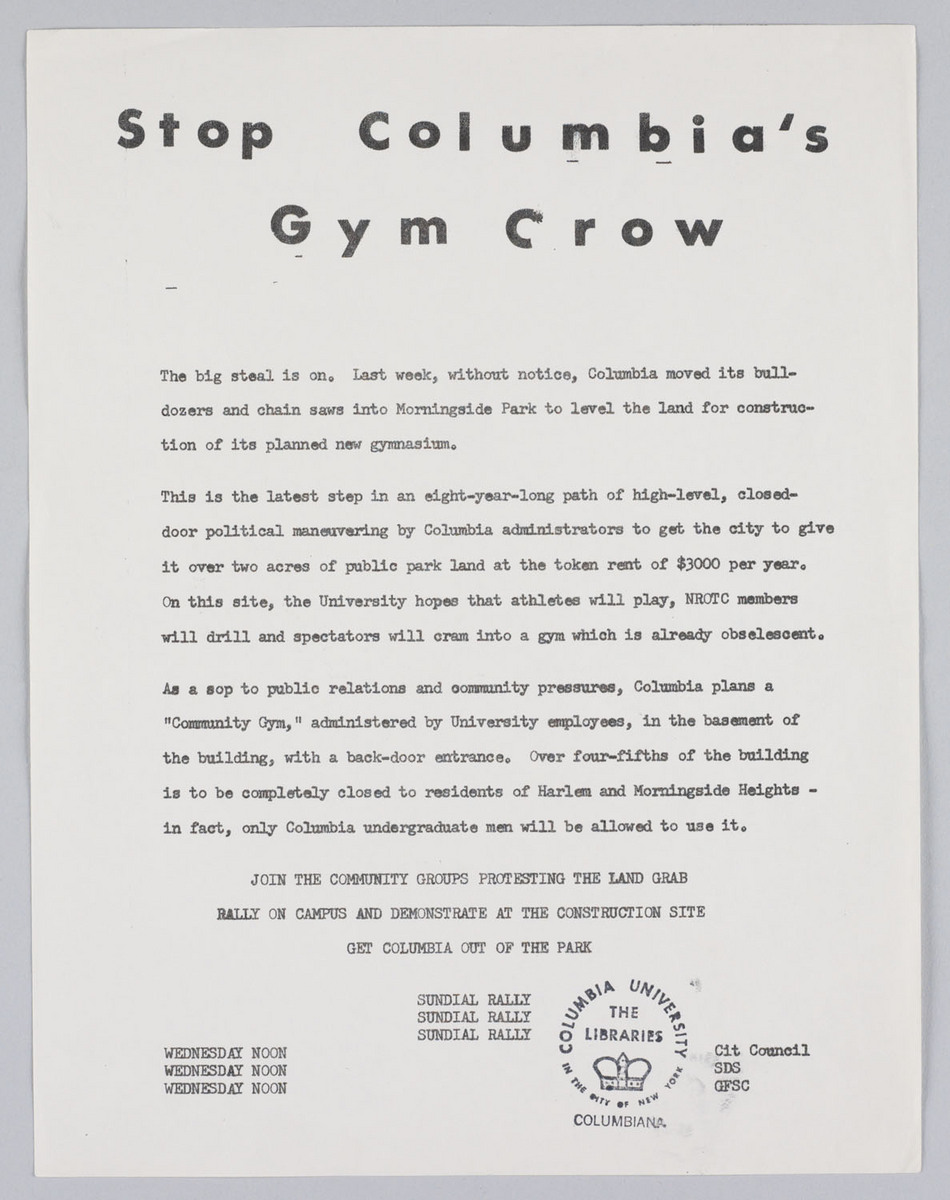

Those opposed to the gym were particularly critical of its design. The building provided access to the University community at the top of Morningside Park along its western boundary, while residents of the surrounding Harlem community would enter on the basement level, along the eastern edge of the park, where they would have access to only a small portion of the building. Separate and unequal access to the facilities prompted cries of segregation and racism. The gym, moreover was intended for the exclusive use of Columbia College students, a fact that did not provide graduate and professional students, as well as Barnard and Teachers College students, much reason to support it. Almost immediately after Columbia began construction on the gym in February 1968, demonstrating Columbia students and neighborhood residents descended on the site in protest.

Protestors tearing down protective fencing

Those opposed to the gym were particularly critical of its design. The building provided access to the University community at the top of Morningside Park along its western boundary, while residents of the surrounding Harlem community would enter on the basement level, along the eastern edge of the park, where they would have access to only a small portion of the building. Separate and unequal access to the facilities prompted cries of segregation and racism. The gym, moreover was intended for the exclusive use of Columbia College students, a fact that did not provide graduate and professional students, as well as Barnard and Teachers College students, much reason to support it. Almost immediately after Columbia began construction on the gym in February 1968, demonstrating Columbia students and neighborhood residents descended on the site in protest.

Brochure: "The New Gymnasium"

In 1959, at the urging of trustee Harold McGuire, the University initiated plans to build a gymnasium for Columbia College students that would sit on two acres of public land just inside Morningside Park. The New York Legislature approved Columbia’s gymnasium plans, which included limited community access, in 1960. Initially, this project boasted the support of the administration, the University trustees, College alumni, the local community, and government officials. Unfortunately, fundraising delays held up construction of the building for several years, allowing interested parties ample time to revise their opinions about the project. By the mid-1960s, the University’s allocation of public land for the project provoked increasingly negative feelings among government officials, community groups and Columbia students.

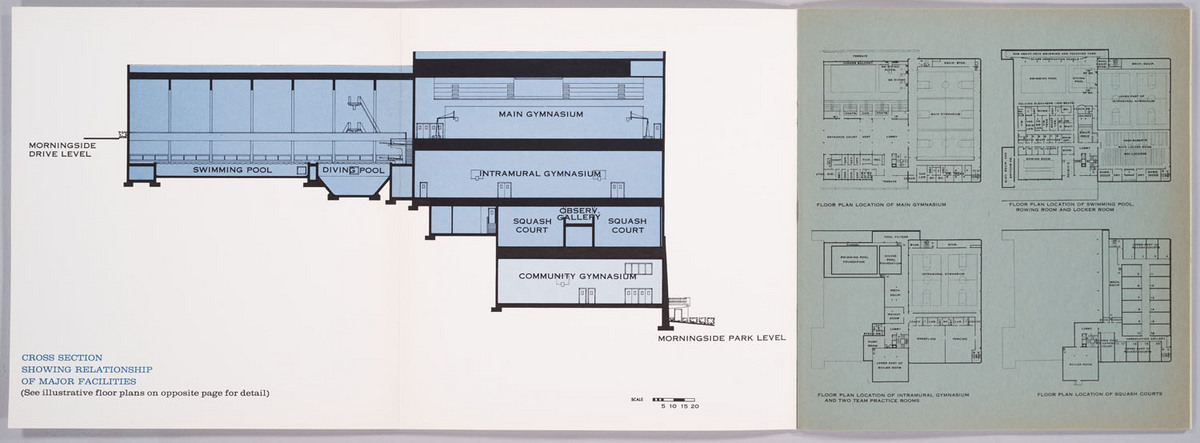

"Stop Columbia's Gym Crow"

The SAS was founded in 1964 by members of Columbia College classes of 1967 and 1968. For several years, the SAS claimed a small membership; most of Columbia’s black students did not join, focusing on their own extra-curricular activities or participating in off-campus political activist groups based in Harlem. On February 18, 1968, the University broke ground on its proposed athletic complex in Morningside Park. The SAS found its galvanizing issue in the gym, arguing that Columbia effectively stole the land from the predominantly black community that had traditionally used Morningside Park. Led by juniors Cicero Wilson and Ray Brown, the organization enlisted the support of the Harlem community and of New York’s leading black activists, and spoke out publicly against the complex, labeling the project “Gym Crow.”

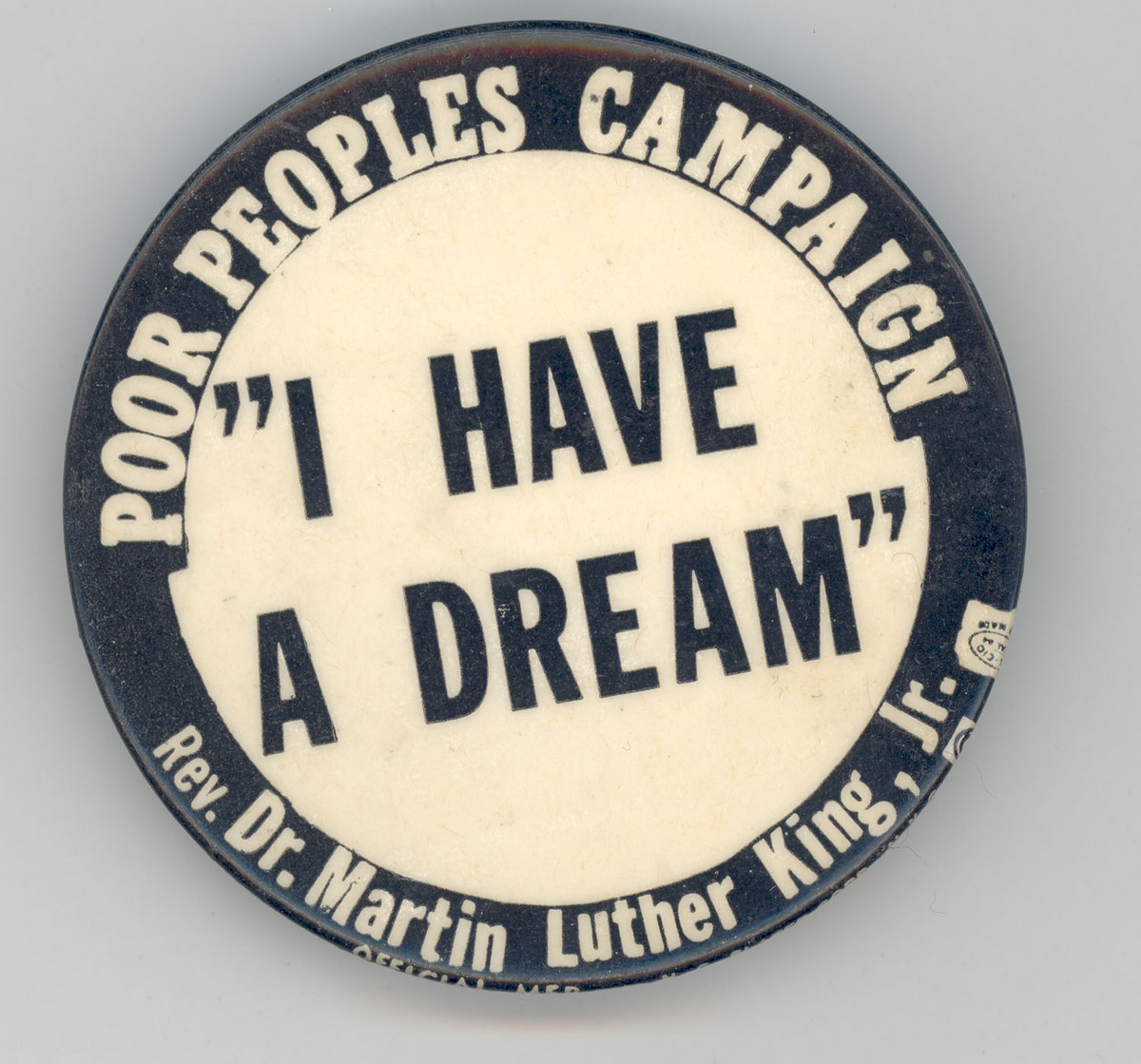

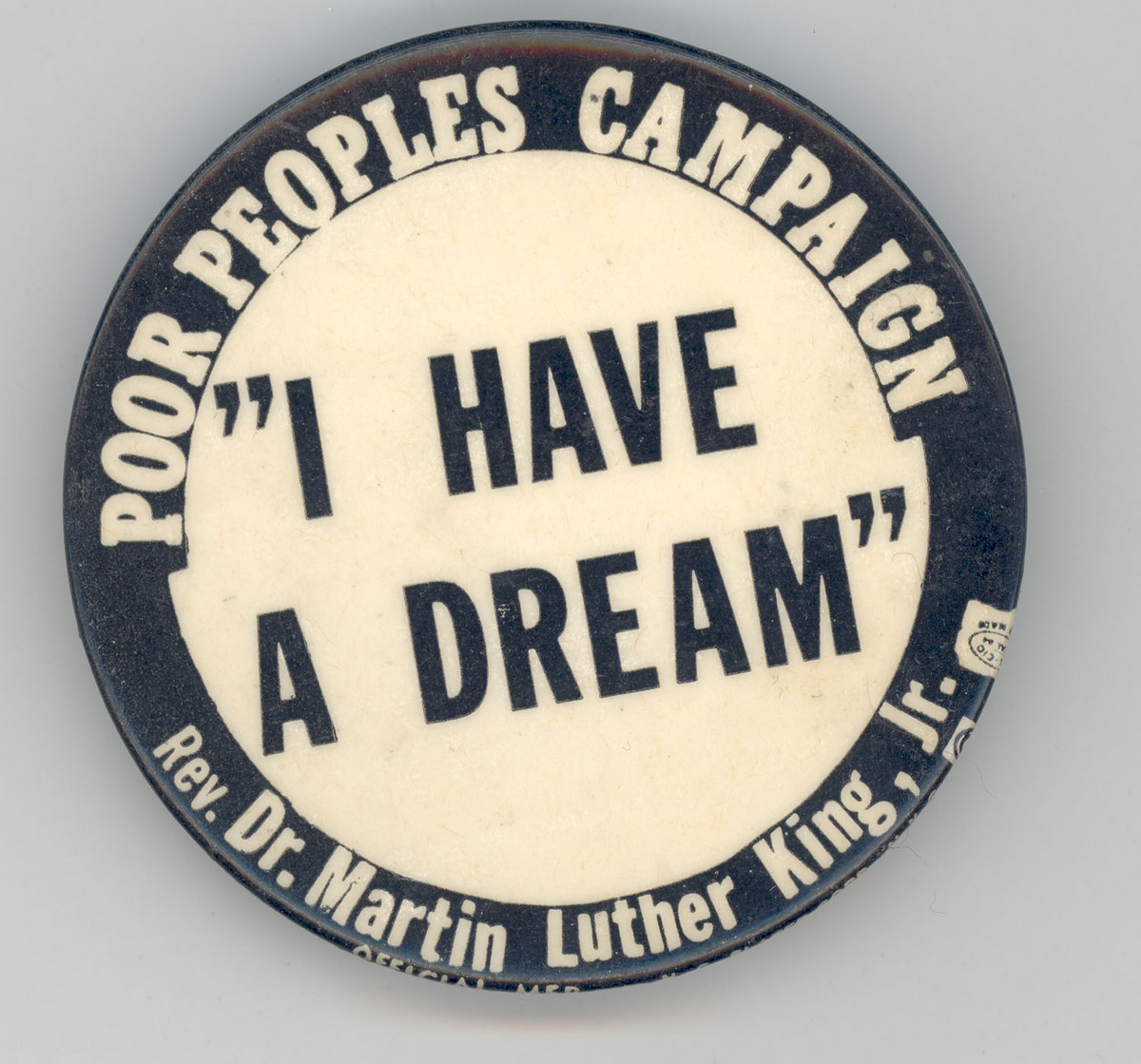

Button: "I Have a Dream," 1968. Courtesy of Frank da Cruz, '71GS, '76E

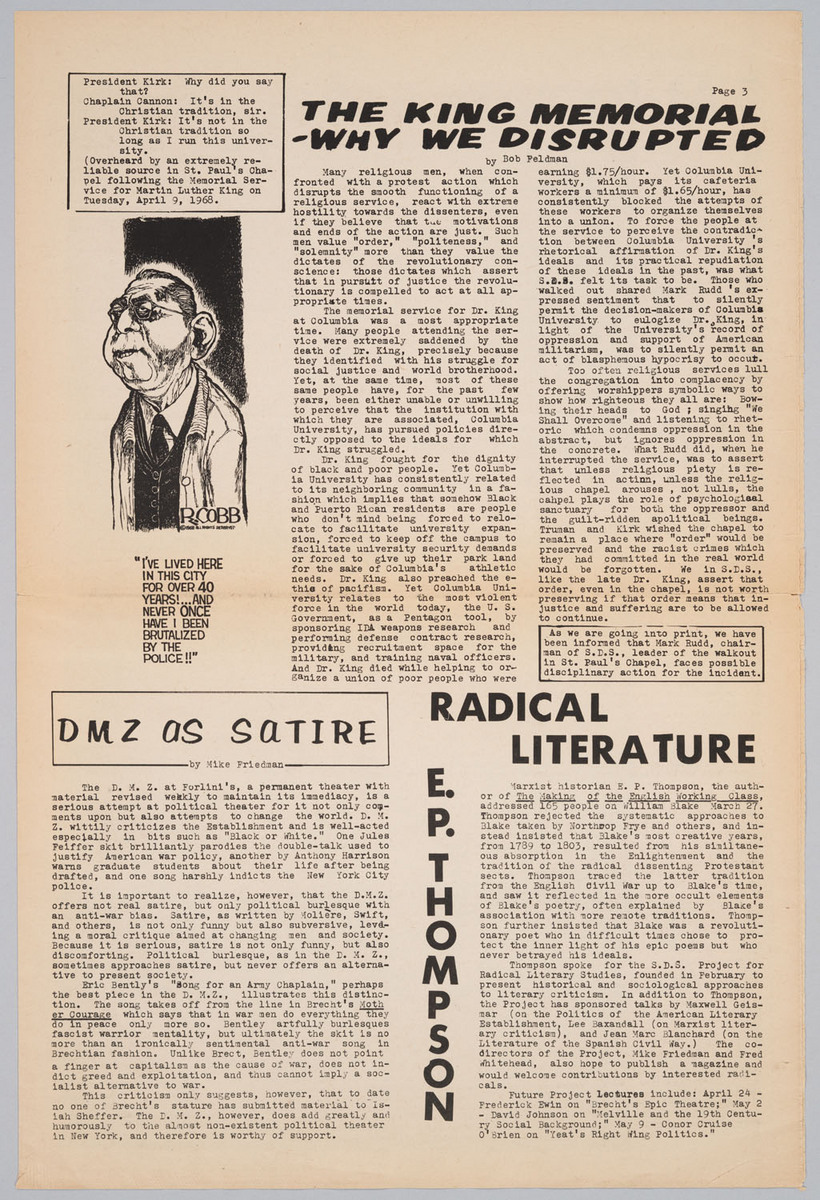

Among the startling succession of events that rocked the nation in the spring of 1968 - and exacerbated tensions on campus - was the assassination of civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. At Columbia, Chaplain John D. Cannon organized a University memorial service to take place in St. Paul's Chapel on April 9.

Crowds Leaving MLK Memorial Service

The King Memorial - Why We Disrupted, p. 3

Mark Rudd and other SDS leaders at a Strike Coordinating Committee Press conference

Reply to Uncle Grayson

Columbia students established a small chapter of SDS in 1965. At no time was Columbia’s chapter of SDS any bigger than 50 core members. At first, the organization was led by the “praxis axis,” a group of students focused on education, recruitment, and radical theory rather than large-scale action. When Mark Rudd was elected chairman of SDS in the spring of 1968, however, he proposed and pursued a much more dramatic “action faction” strategy. The March 1968 disciplinary action against the “Low Six,” the continued protest against IDA and open recruitment on campus, and the heated debates ensuing about the Morningside Park gymnasium gave Rudd and SDS a more thorough platform on which to act. The group organized a major rally for April 23, to take place on Low Plaza at the Sun Dial.

SDS button

This image may not be reproduced without the permission of Frank da Cruz. Please contact the University Archives for further information.

Button: "I Have a Dream," 1968. Courtesy of Frank da Cruz, '71GS, '76E

Among the startling succession of events that rocked the nation in the spring of 1968 - and exacerbated tensions on campus - was the assassination of civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. At Columbia, Chaplain John D. Cannon organized a University memorial service to take place in St. Paul's Chapel on April 9.

Columbia Daily Spectator, April 30

Students being chased by police

Permission to reproduce this image must be obtained from Paul Cronin. Please contact the University Archives for contact information.

After the police bust

"Kirk Bans Pickets in CU Buildings: September 25, 1967 "

On April 21, 1967 the first student-to-student clash erupted when 500 students favoring the policy of open recruitment on campus confronted 800 anti-recruitment demonstrators. Student disruption of military recruiters prompted University President Grayson Kirk to issue a ban against picketing and demonstrations inside all University buildings as of September 1967.

1968: Columbia in Crisis

Columbia University Libraries

The occupation of five buildings in April 1968 marked a sea change in the relationships among Columbia University administration, its faculty, its student body, and its neighbors. Featuring documents, photographs, and audio from the University Archives, 1968: Columbia in Crisis examines the the causes, actions, and aftermath of a protest that captivated the campus, the nation, and the world. This online exhibition is based upon a physical exhibition of the same name which was on display in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library from March 17 to August 1, 2008. Unless otherwise noted, all images and documents are from collections found in the Columbia University Archives.

Exhibit Curator Jocelyn Wilk