Suggested Donation Levels

What have you learned?

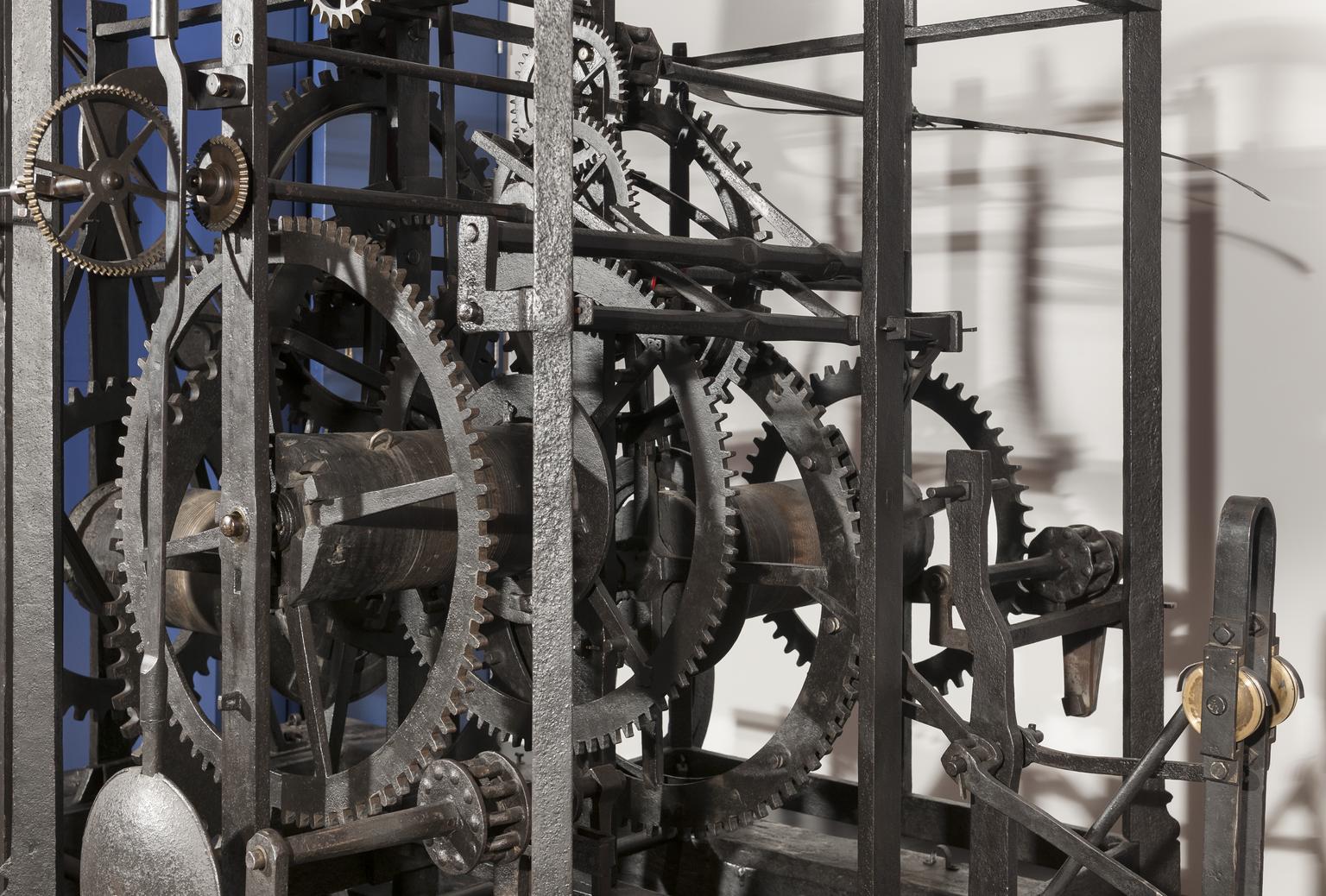

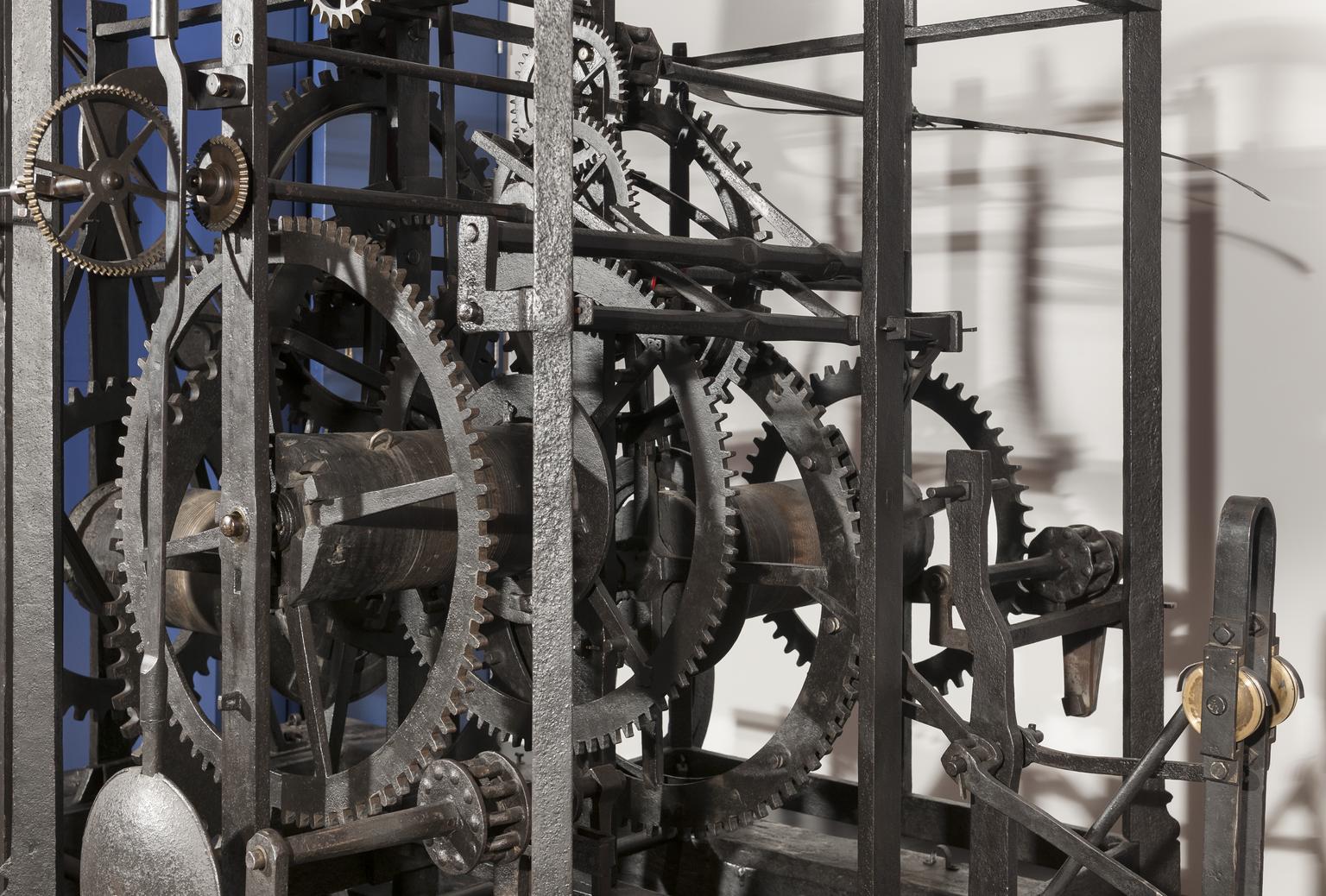

Wells Cathedral clock

A few cathedrals and wealthy churches are known to have had clocks: this example from Wells Cathedral was made in 1392 and is one of the oldest surviving clocks in the world. However, such instruments were exceptions: they required precision craft skills on the part of their makers, and were expensive to build and to maintain.

Image 1 - Wells Catedral clock - Science Museum London

Image 2 - Wells Cathedral clock, detail, - Science Museum London

Image 3 - Wells Cathedral clock, detail - Science Museum London

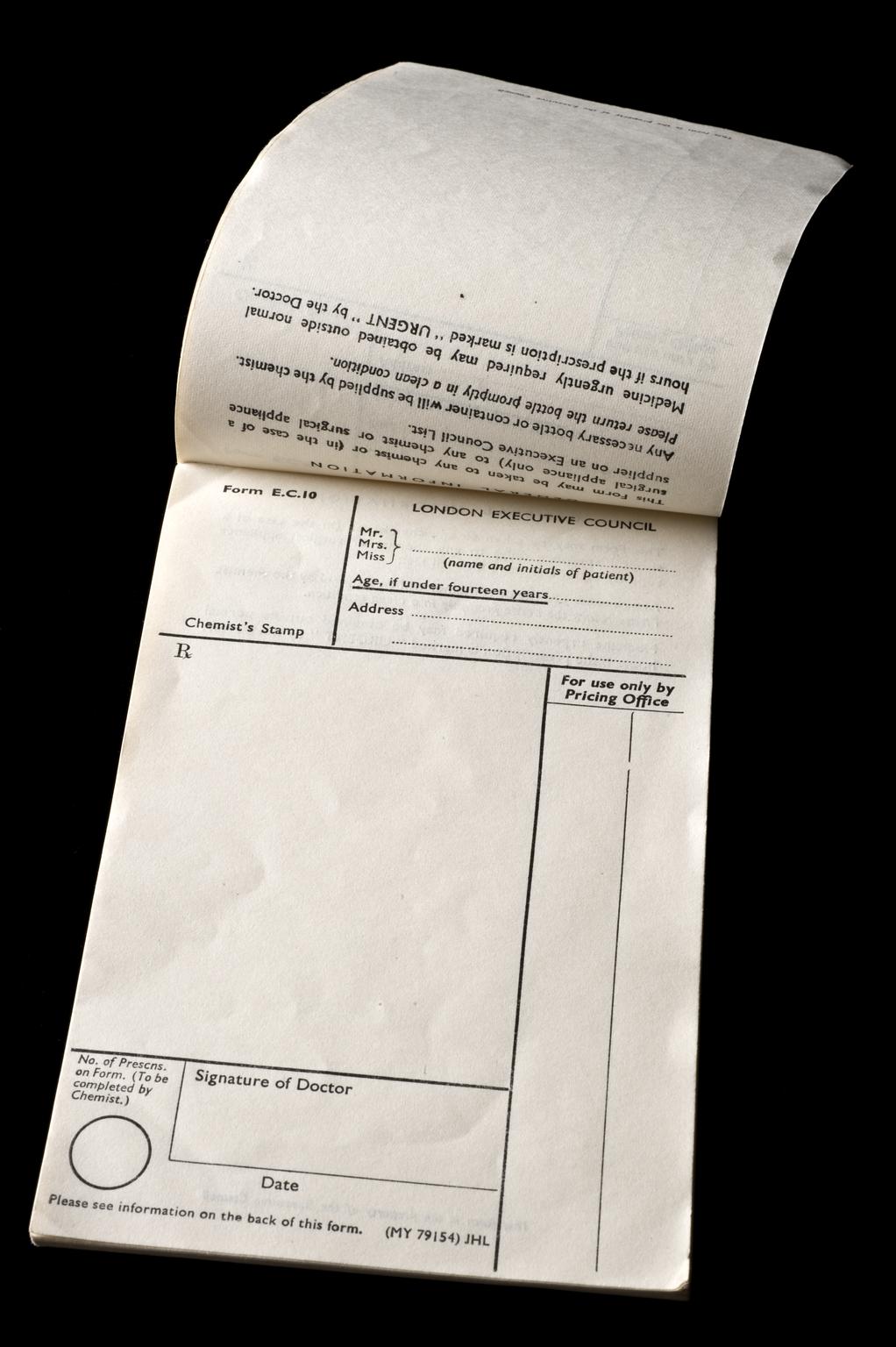

Prescriptions and Time

Have you ever been issued a prescription? Think what instructions the doctor gave you. These will usually say when and at what intervals a medicine should be taken: for example, two pills per day, one after you wake up and one before you go to bed.

Some instructions might be more prescriptive in certain respects and less in others: for example, you can take the medicine when you feel the need, but should not use it again within four hours of the previous dose.

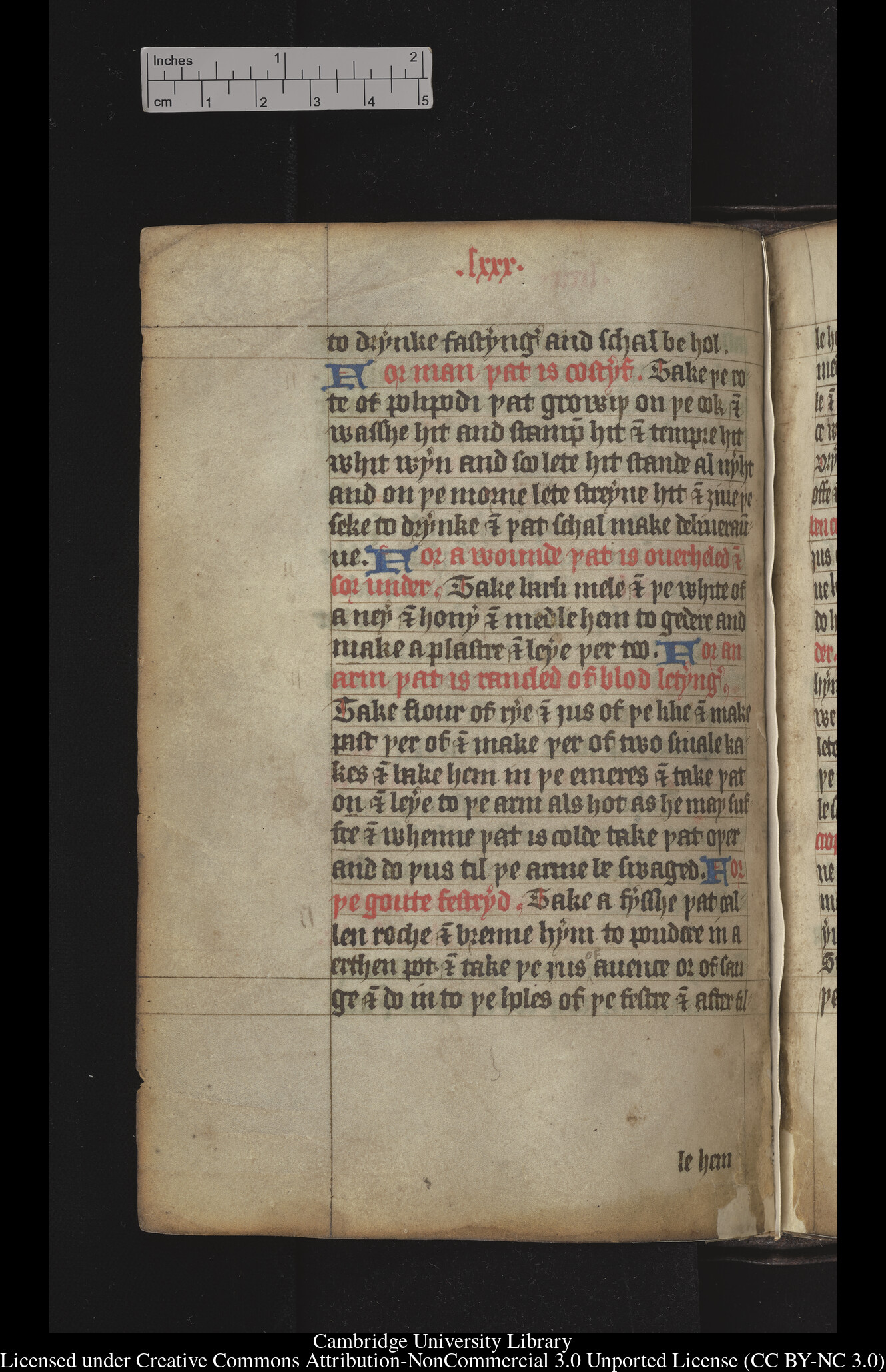

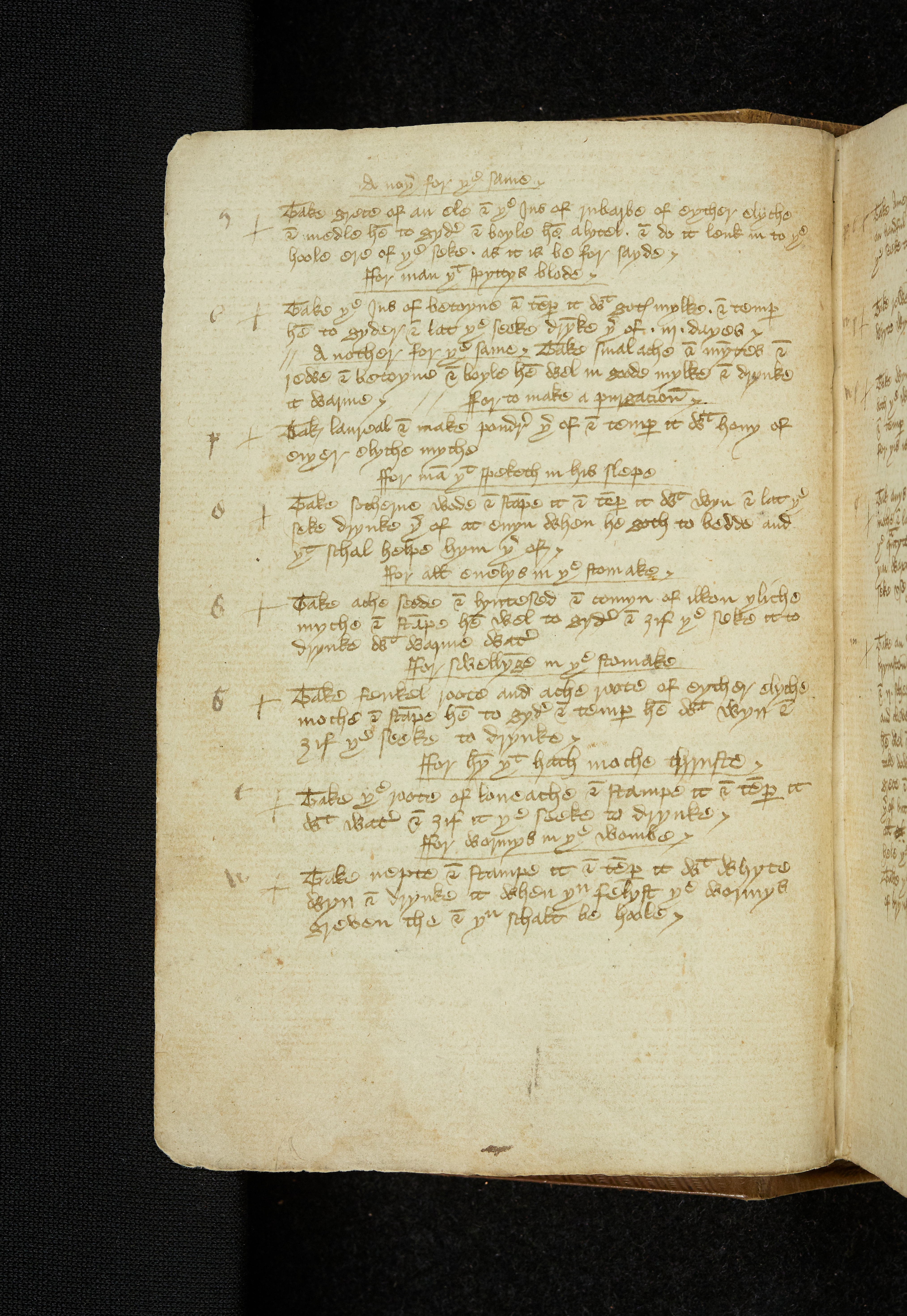

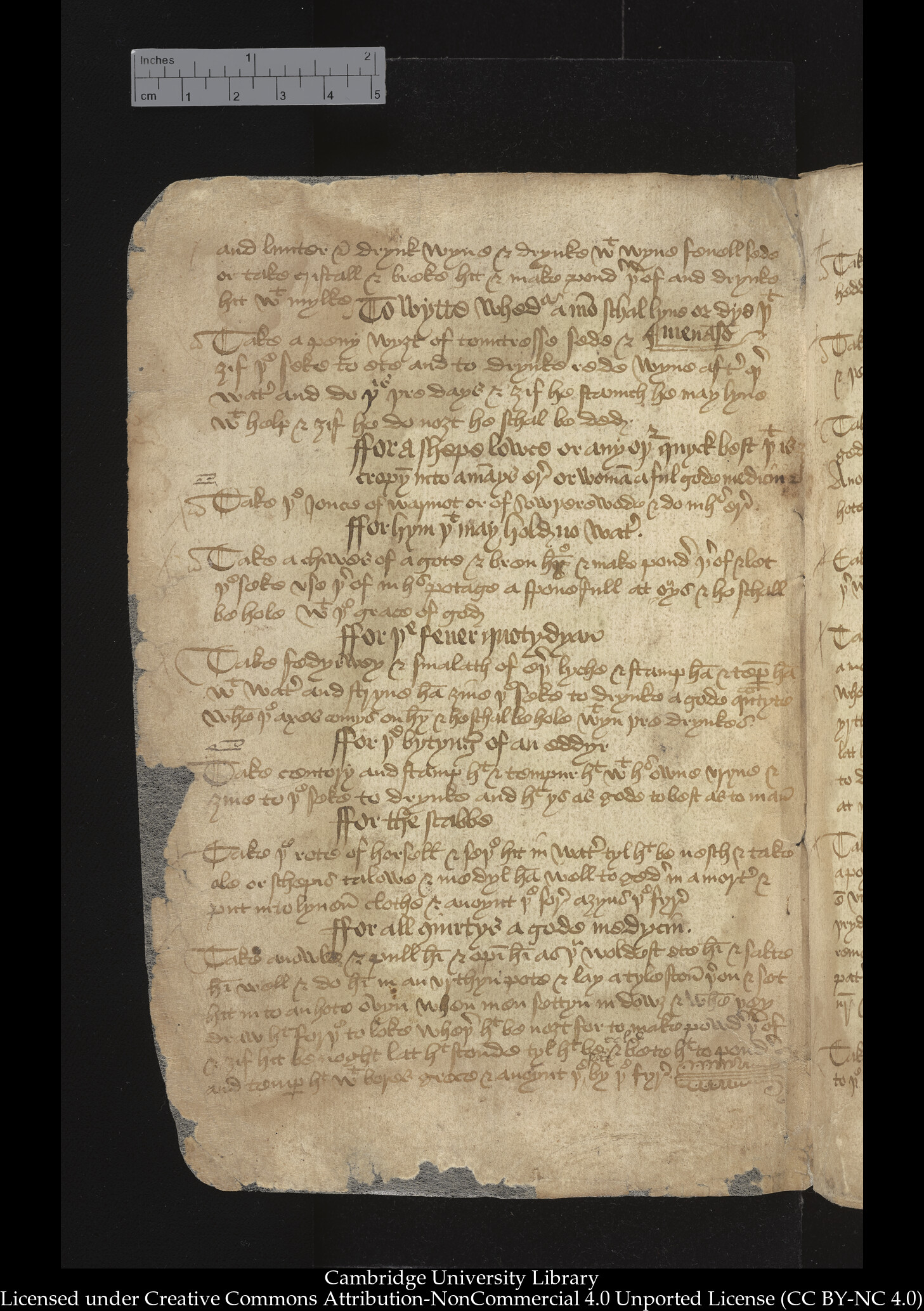

How to prescribe without a clock or a watch - Medical miscellany

Most commonly, these steps were attuned to the rhythms of the day. This remedy 'For a man that is costyf' - that is, constipated - uses the root of a fern known as 'polypody', which grows on oak trees. It should be washed, crushed, and then mixed with white wine: 'and so let it stand all night and on the morrow strain it'. The patient should then be given the liquid to drink, 'and that shall make deliverance', the recipe concludes.

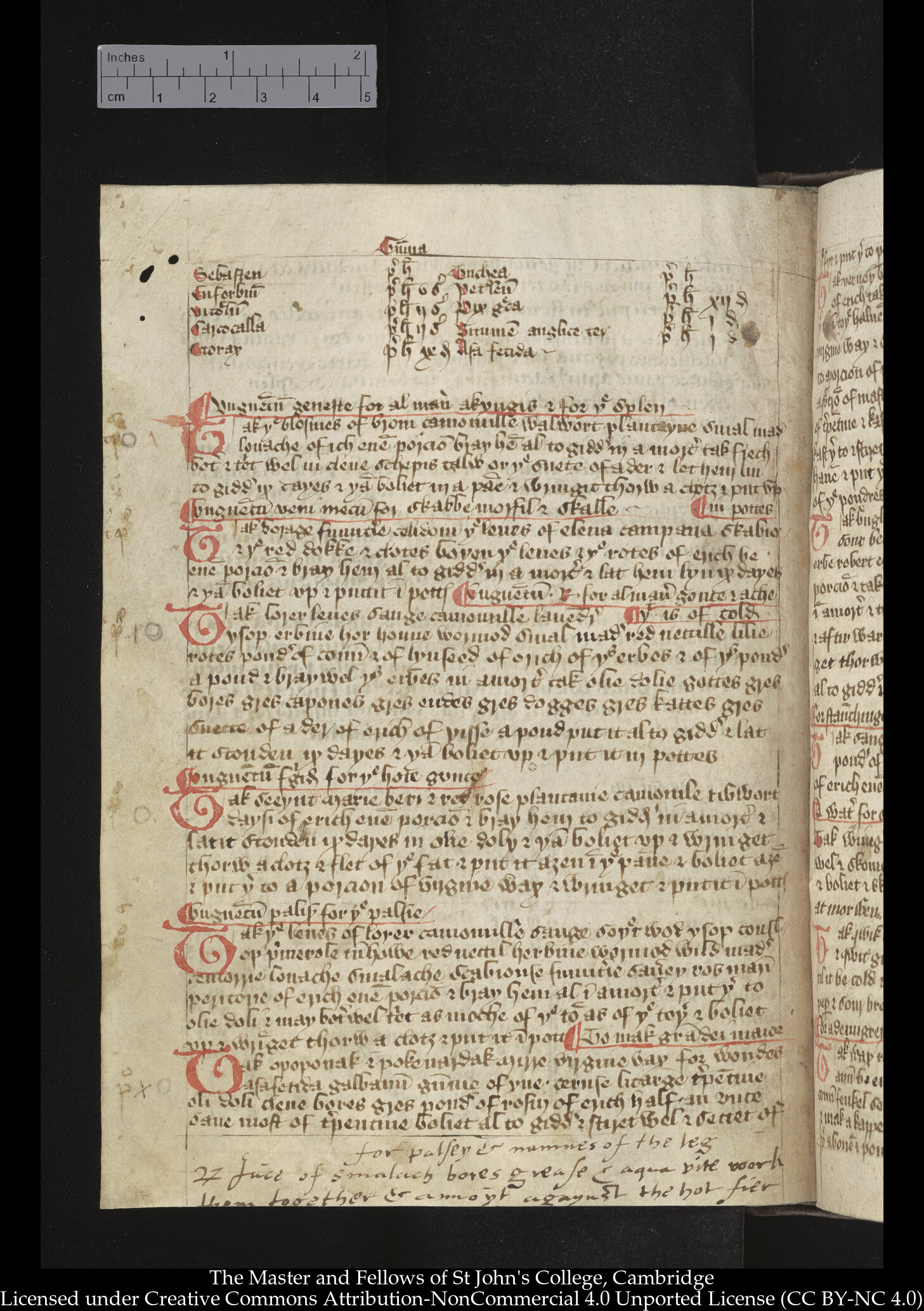

An ointment for skin disease

The second recipe on this page is for an unguent - an ointment or salve - known by the Latin name 'veni mecum', meaning 'come with me'. The rubric - the title of the remedy, which is underlined in red - states the three ailments it can address: 'skabbe, morfil and skalle', all types of skin diseases involving scabs, scaly skin and pustules.

The herbal remedy took rather longer to prepare than the previous one. It was made by taking the leaves and roots of borage, fumitory, celandine, elecampane, scabious and red dock, and another plant called 'clotes boyen', all in the same quantity. 'Bray [i.e. crush] them all together in a mortar,' the recipe instructs, 'and let them lie nine days, and then boil it up and put it in pots.'

The time it took to make, and the recommendation on storage, suggests that the unguent was to be made in batches by a healer or apothecary, and kept until it was needed by a patient.

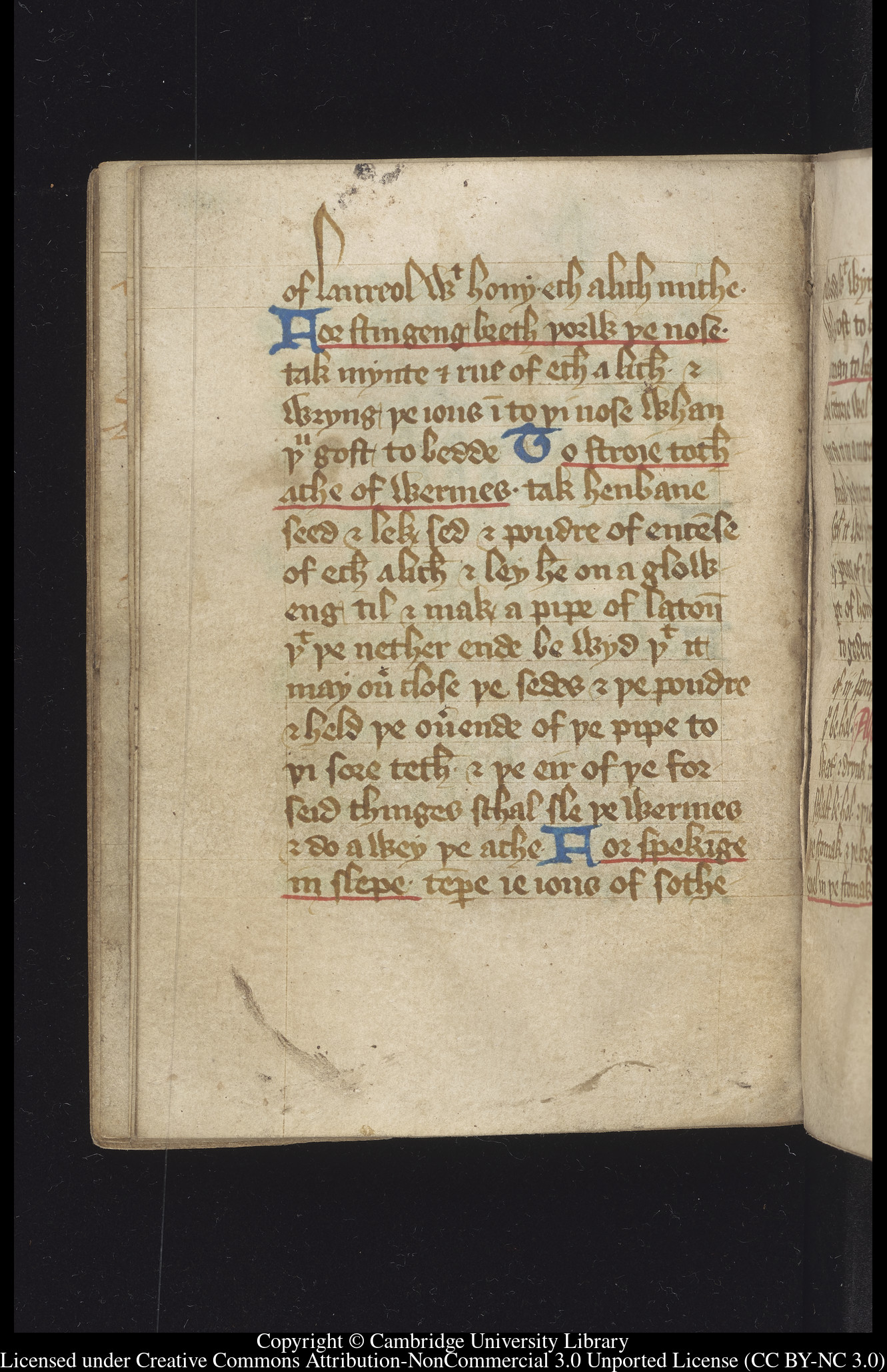

'Take mint and rue of each alike and wring the juice into thy nose when thou goest to bed.'

This manuscript contains a cure 'for stinking breath through the nose', and instructs the reader as follows:

'Take mint and rue of each alike [i.e. in the same quantity] and wring the juice into thy nose when thou goest to bed.'

A drink 'to cleanse the breast'

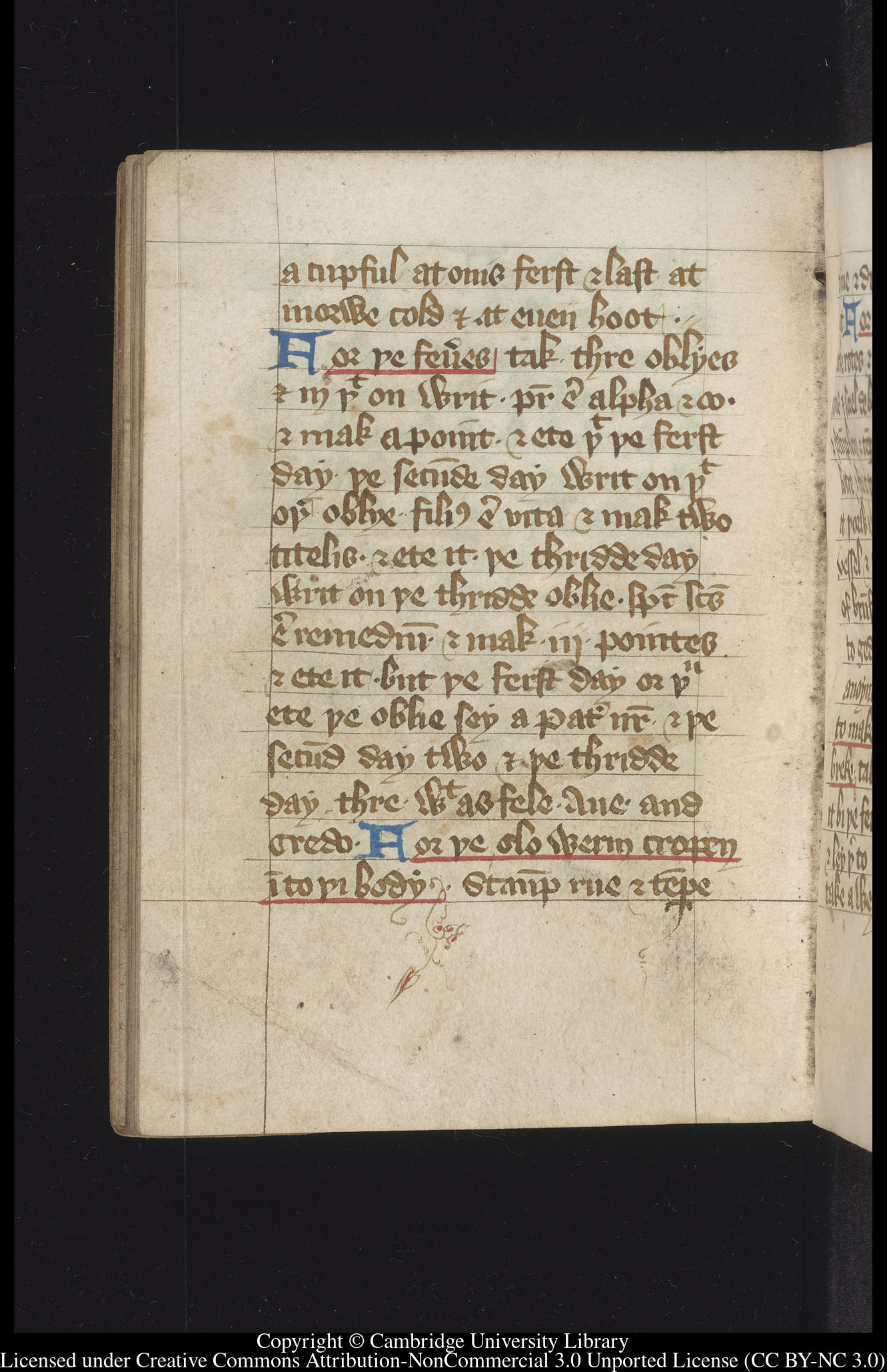

The pot was to be closed up, buried in the ground and left for ten days. After that time had elapsed, the pot should be exhumed. The final instructions are shown here: the patient should drink 'a cupful at once, first and last, at morrow cold and at even hot': that is, cold in the morning and hot in the evening.

'Drink it when thou feelest the worms grieven thee and thou shalt be well'.

This treatment is for 'worms in the wombe'. 'Worms' appear in many different contexts in medical recipes and they might refer to a parasite or organism living on or in the body - but they may also refer to something that could not be seen but was thought to be the cause of a variety of different ailments.

The key ingredient is 'nepte' - probably the herb we now know as catnip or catmint. Like the cure for constipation, the herb is crushed and then tempered in white wine in order to make a drink. The reader is told, 'Drink it when thou feelest the worms grieven thee and thou shalt be well'.

How long is 'a good while'?

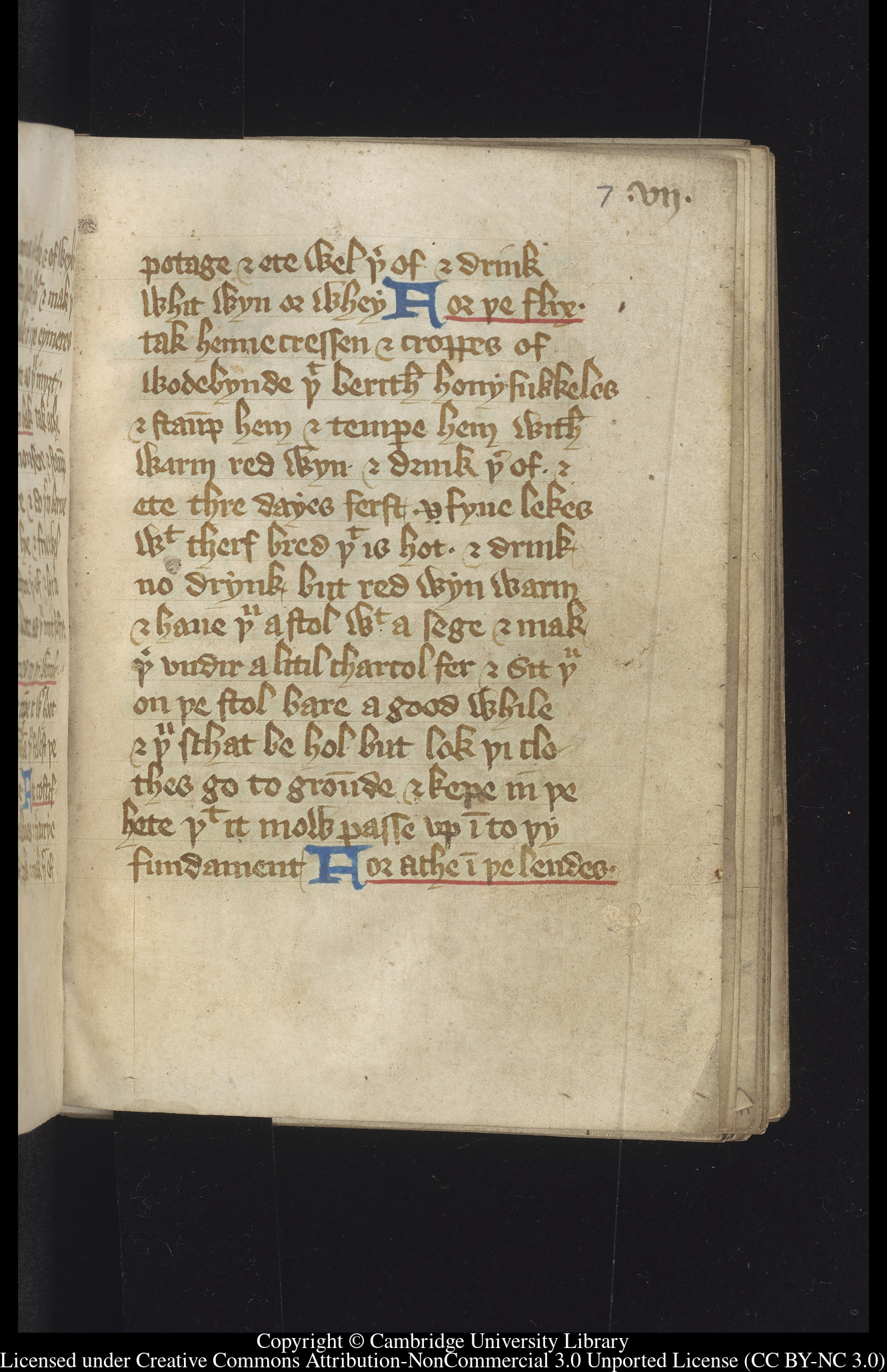

This remedy for the 'flix' (diarrhea or dysentery) prescribes first a special drink and diet. It then suggests a rather more curious cure - a sort of fumigation for one's bowels:

'And have thou a stool with a seat [i.e. like a toilet seat] and make thereunder a little charcoal fire and sit thou on the stool bare a good while and thou shalt be well - but look thy clothes go to the ground and keep in the heat, that it may pass up into thy fundament.'

How long is 'a good while'?

Medical recipes and charms Cambridge, University Library

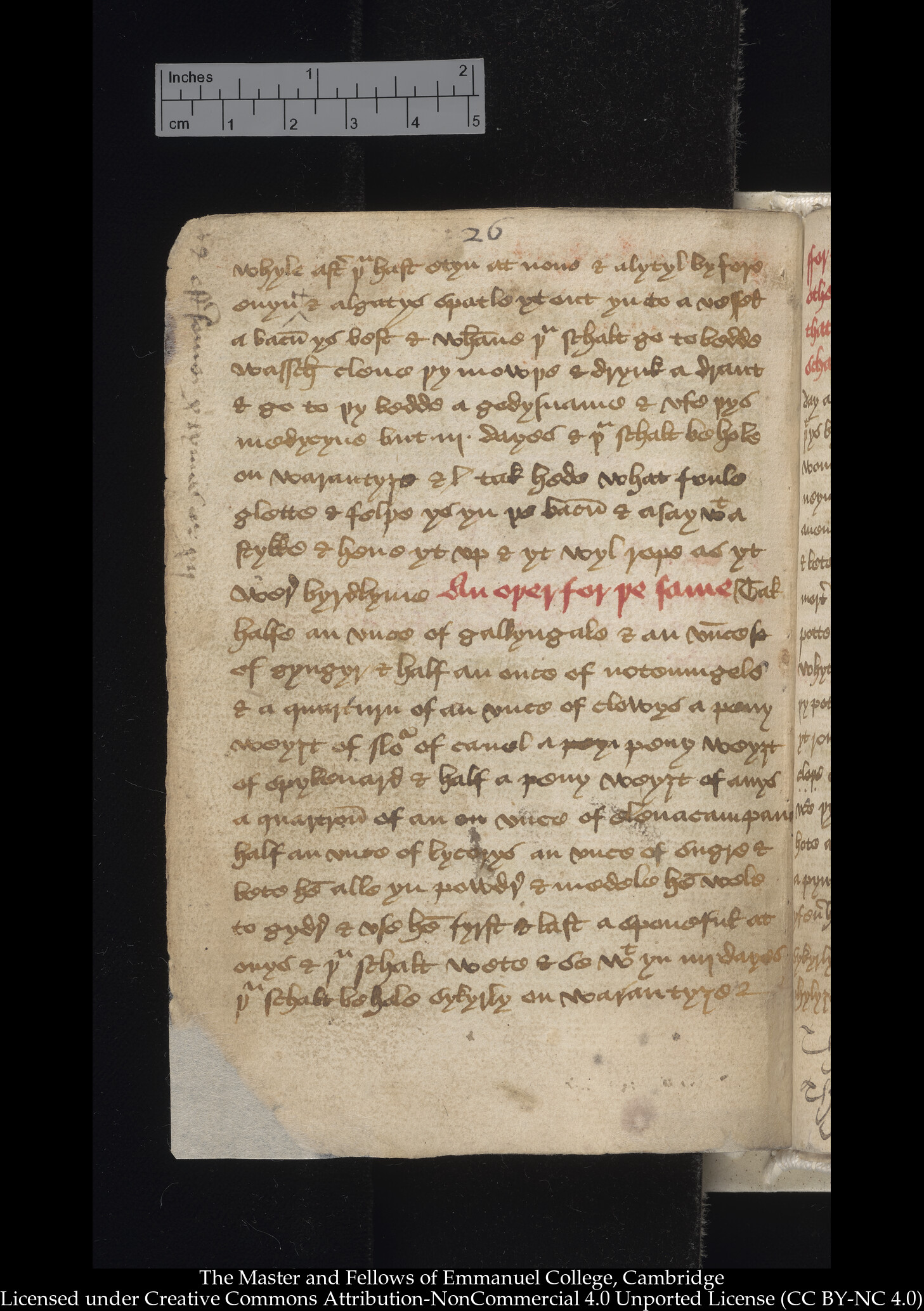

Cure 'all manner of ache' with mouthwash

'The three pennyweight of the root of pellitory of Spain and a half pennyweight of spikenard and grind them together and boil them in good vinegar. Take a saucerful of honey and five saucerfuls of mustard, and when the licour that is heated is cold, put thereto thy honey and thy mustard and mix them together.'

There then followed the instructions for its use:

'And then let the patient use thereof half a spoonful at once and hold it in his mouth all so long as a man may say two Credos, and then spit it out into a vessel and take another and thus do ten times or twelve...'

The prayer referred to here might be the Nicene Creed or the Apostles' Creed, two similar declarations of a person's belief in the Trinity of God, Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit. They would take approximately a minute (Apostles' Creed) or a minute and a half (Nicene Creed) to recite in full.

A strange remedy for gout

This rather strange remedy for gout - 'a good medicine' according to the rubric - involves plucking and gutting an owl, 'as thou wouldst eat him'. The unfortunate bird's body was to be put into an earthen pot, a lid put over the top, and then baked in the oven.

But how do you know how long to bake your owl for - and at what temperature?

The recipe explains, 'Set it into a hot oven when men set in dough, and when they draw it forth, look whether it [the owl] be ready for to make powder thereof' - so, roughly the same amount of time it takes to bake some bread. 'If it be not [ready], let it stand til it be, and beat it to powder and temper it with boar's grease and anoint the sore by the fire.'

Time and Medieval Time

Cambridge University Library

How did medieval people know when to take their medicine and for how long? Or the amount of time needed to prepare its ingredients? Through the manuscripts digitised by Cambridge University Library's Curious Cures project, this exhibition explores the creative, imaginative solutions that healers and physicians used to guide the correct preparation and administration of their medicines.

Exhibition Quiz:

Do you know your clocks from your owls...